“Good Cop and Bad Cop Left for the Day. I’m a Different Kind of Cop.”

The greatness of The Shield

“The Shield clearly and self-consciously belongs to the type of quality television that intentionally troubles its audience’s sense of right and wrong.” —Glyn White

In 2010, I watched the entire series of FX’s The Shield.

More than a decade later, during the lockdown, I re-watched it. It was even better than the first time around. Here is my conversation with Richard Hanania and Marc Andreessen about the series:

So many TV shows depict only the clean and sanitized Hollywood version of LA.

Watching The Shield, I was instantly captivated by the familiar scenery of rundown and dilapidated buildings in East Los Angeles.

While The Sopranos, Mad Men, and The Wire are undoubtedly the greatest literary TV shows, The Shield might be the greatest drama.

The only other series that comes close is Breaking Bad.

But The Shield came first.

The series plumbed the same depths as HBO’s prestige shows: power and violence, work and family, addiction and sexuality.

Some have compared it to The Wire. Both shows depict cops and criminals as complex human beings capable of both kindness and cruelty.

But there is a key difference.

The Wire portrays sympathetic characters in various circumstances trapped in systems beyond their control.

The Shield depicts self-serving characters making ugly decisions to contain violence and further their own interests.

The Wire is for Rousseau; The Shield is for Hobbes.

The pilot aired in 2002, centering around a police station in a crime-plagued East Los Angeles neighborhood.

When the show premiered, it was met with criticism from the Parents Television Council. Police associations across the U.S. reacted with fury because the show portrayed cops as amoral monsters. This led to advertiser boycotts.

Interestingly, though, the first episode is structured so that the “audience identification” character is Terry Crowley: a handsome detective working with the police captain to bring down a corrupt unit.

These kinds of characters make audiences comfortable and give them a place to judge all the other characters.

The Shield then kills Terry off at the end of the pilot.

From that point on, there’s no safe, comfortable place to watch the show.

The actual main character of the show is Vic Mackey, a police detective who leads the morally-compromised Strike Team, an anti-gang unit tasked with reducing street crime in the city.

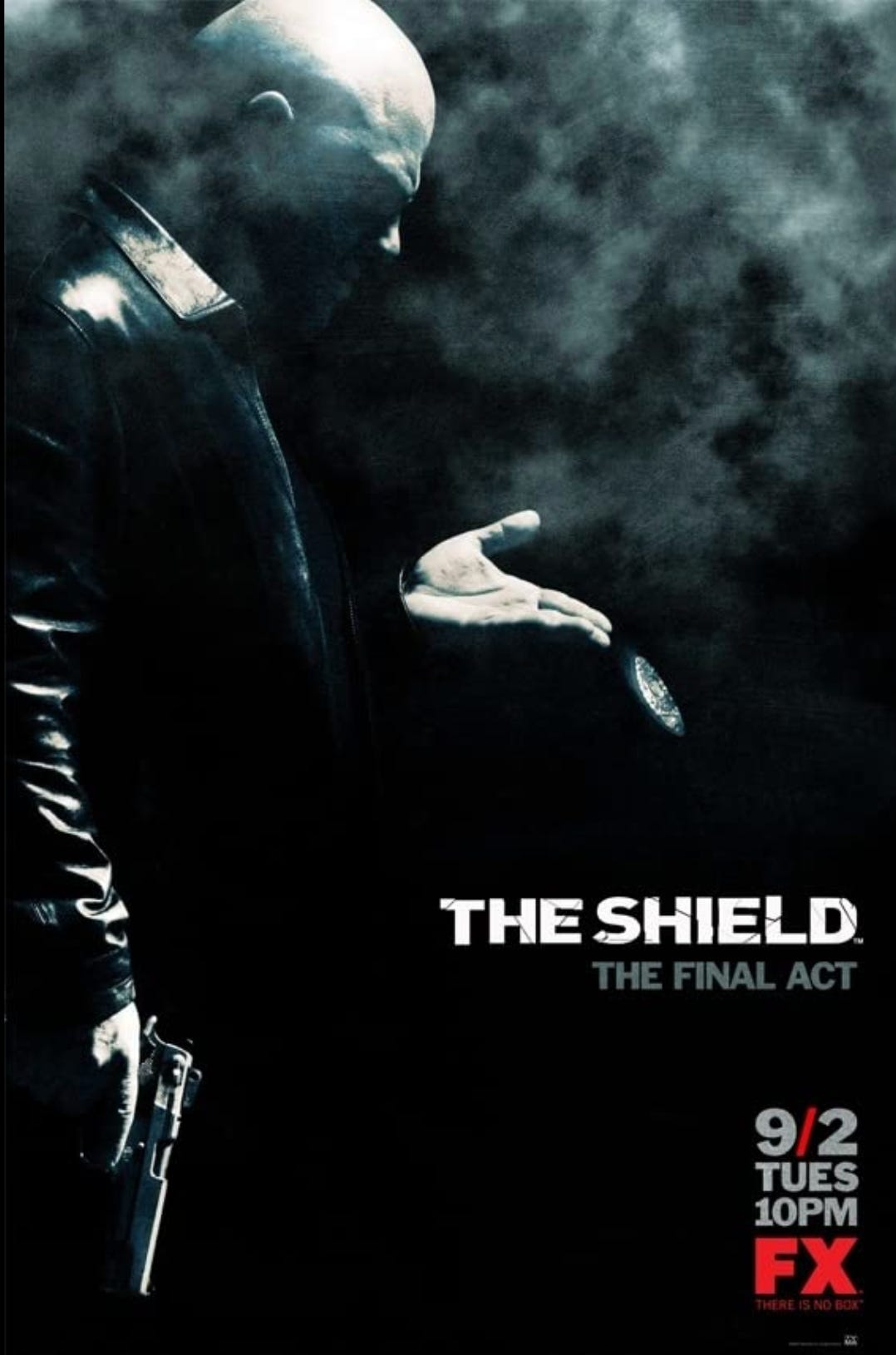

Like Tony Soprano before him, the protagonist of The Shield is a bald, stocky, charismatic boss.

Vic is also incredibly intelligent, utterly ruthless, and astoundingly resourceful. Watching him stay one step ahead of his captain, Internal Affairs, and LA drug lords is one of the most absorbing aspects of the show.

The captain of the precinct is David Aceveda, an ambitious and relatively young man whose main ambition is to become the mayor of Los Angeles. He hopes that by cleaning up the precinct and exposing police corruption while simultaneously reducing crime, he can bolster his political career. Acaveda knows Vic and his team are corrupt, but can’t prove it. He describes Vic as “Al Capone with a badge.”

Acaveda then appoints a detective named Terry Crowley to join the Strike Team to work with Vic and the other three members of the team.

Gradually, Vic, along with Shane, Ronnie, and Lem discover that Terry Crowley is a mole. Acaveda sent him to dig up dirt on the Strike Team.

The Strike Team later raids a drug dealer’s house. Vic kills the dealer, and then uses the dealer’s gun to shoot Terry Crowley in the face. He then carefully replaces the gun in the dealer’s hand, to make it look like Terry was killed in a gun fight.

All of this happens in the pilot.

Within the same episode, Vic interrogates a child molester who is suspected of kidnapping a little girl.

The man smirks, looks at Vic, and asks, “Your turn to play bad cop?”

Vic Mackey delivers the line that encapsulates the theme of the series: “Good cop and bad cop left for the day. I’m a different kind of cop.”

Vic then beats the man senseless until he reveals the girl’s location.

Despite murdering a fellow police officer—who the audience is set up to believe is the protagonist/good guy—in the very first episode, Vic successfully gains the viewer’s sympathy throughout the rest of the first season.

He has a wife and two children with autism who require medical care. Vic cuts corners and partners with criminals to ensure he can afford medical treatment for his kids.

He partners with drug dealers to get a cut of their profits, plants evidence, commits murder, cheats on his wife, and lies to everyone around him.

The Shield has been called “the inverse of The Sopranos.” Both are about men who do bad things but show glimpses of humanity, leading you to think they can be redeemed. But one is about a criminal and the other is about a cop.

The Sopranos invited the audience to like a character who was traditionally the villain. The Shield took a classically sympathetic figure (a cop) and made him into a hero, a monster, or something in between.

Is Vic Mackey worse than Tony Soprano? Probably, yes.

But it’s not entirely straightforward. Tony never does anything particularly noble. Vic repeatedly rescues women and children from the hands of bad men.

At one point in the first season, Vic literally rescues a drowning baby:

Tony never did anything this good.

But because he is a criminal by trade, we hold Tony to a lower standard. We expect him to be a bad guy, so whenever he does something good, we are pleasantly surprised.

As a cop, we hold Vic to a higher standard. We expect him to be a good guy (he’s supposed to rescue babies!), so whenever he does something horrible (which is often) we are repulsed.

This contradiction between our expectations and the characters’ behavior is why an argument can be made that Vic is worse than Tony.

In the show’s first year, Michael Chiklis (who plays Vic Mackey) won the first acting Emmy for a basic cable drama. Still, the show does not have the reputation it deserves.

Usually, what happens with good shows is that after the first three seasons or so, it starts to fall apart. Even the best shows have one or two weak seasons.

But with The Shield, the first season is good. And each season is arguably better than the last. They got some great guests for each season, too.

Season 4 with Glenn Close as the new police captain is fantastic. Her dynamic with Vic was fascinating. The whole season is an allegory of the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

Season 5 with Forest Whitaker as an Internal Affairs Lieutenant appointed to investigate Vic and the Strike Team is perhaps even better. Whitaker’s portrayal exudes such desperation and repugnance that the viewer almost wants Vic to get away with his crimes.

The series creator called Whitaker’s character an “anti-villain.” An anti-hero is a sympathetic character who does bad things. An anti-villain is an unsympathetic character who does good things.

The series finale, “Family Meeting,” is considered by many critics as one of the best in TV history.

One reason this show never reached the same level of popularity as The Sopranos is that making excuses for criminality is fashionable. Identifying with a mob boss who does bad things makes educated viewers feel sophisticated and regular viewers feel cool.

The Shield never won over educated viewers the way The Sopranos did because making excuses for the actions of an evil cop just isn’t as fashionable as making excuses for an evil criminal. Still, the series did well with general audiences. The Shield was the highest-rated basic cable drama of its time, because regular people are inclined to like cops.

Generally, educated people like TV shows that make them feel smarter than they really are. The Shield was too straightforward, which is another reason why it never got the audience it deserved. In contrast, True Detective, a good show with a mediocre ending, had widespread popularity because Rust Cohle made viewers feel smart.

Because The Shield was never concerned with taste or restraint, it was a funnier and more honest depiction of male culture than many other quality dramas.

In one of the episodes, the Strike Team goes to a strip club. At the end of the night, one of the guys (Shane) wants to go back inside to get a phone number from one of the women. The other guys make fun of Shane, saying she didn’t really like him. Shane replies “She was pushing her ass up against me, man, they don’t just do that for anyone.”

In The Sopranos, Tony and his guys drink wine.

In The Shield, Vic and his guys drink beer.

A quote from Shawn Ryan, the series creator:

“There are people who don’t want to believe they’re making television. It’s easier for them to believe they’re film auteurs than to embrace that this is a different genre and that there’re ways to take advantage of that genre. I wasn’t going to Scorsese film festivals in Greenwich Village as a kid. I was watching Brady Bunch repeats. I didn’t walk into this business with an attitude toward television.”

Something that makes this show especially interesting is that it is loosely based on actual events that took place in Los Angeles in the 1990s.

In the late 1980s, East Los Angeles experienced a rise in violent crime. The LAPD created CRASH (Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums). This team was charged with reducing street crime. It succeeded. Gang-related crime fell from 1,171 incidences in 1992 to just 464 in 1999.

Vic Mackey (protagonist of The Shield) is a composite of 3 real LAPD officers from the CRASH unit: David Mack, Rafael Perez, and Nino Durden.

All three officers were later arrested. They testified that the officers slowly began to mimic the gangs they were charged with combatting. The Guardian reports that, “They wore skull tattoos, displayed the mannerisms of gangsters, and hung out with—and even on occasion worked for—Suge Knight,” and “CRASH framed, beat, and shot anyone who got in their way.”

The show’s creator, Shawn Ryan, based much of the series and characters from those actual events in LA. As Ryan has stated, “There were cops who were running roughshod over this poor ethnic neighborhood and yet they were effectively stopping a lot of crime. It was an interesting ethical question.”

To distance the show from real life, none of the four Strike Team detectives in The Shield are ever seen wearing a police uniform.

And of the uniformed officers who appear on the show, their badges were depicted as being on the right side of their uniform (rather than the left, which is where real LAPD officers place their badge). This is to stress that the show very much takes place in a fictionalized world—even though it is in part based on real events.

If you judge Vic Mackey and his Strike Team (and the real-life CRASH team) by their statistical results, they are arguably assets. But if you judge them by their crimes, they are villains.

Vic’s criminal activities include controlling the sale and distribution of narcotics, colluding in murders to maintain the smooth running of the local drug trade, personally supplying drugs to informants to keep them on his side, intimidating witnesses to his own and his associates’ illegal activities, beating, torturing, and intimidating suspects, and murdering another cop.

Here’s an example of a morally ambiguous subplot: Vic partners with a drug lord who has agreed not to let his dealers sell at schools or to children. Vic is aware that if he arrests this guy, someone else will likely take his place and may not be so open to the idea of avoiding the selling of drugs to kids. So Vic makes a deal with him, agreeing to look the other away in exchange for a cut of his earnings.

In season 3, a new guy arrives, kills the old drug lord, and takes over his territory. He then begins selling heroin to kids. He rapes a little girl and tattoos her face. Vic later breaks into this guy’s house, seizes him by the hair, and burns half his face on a stovetop.

Not all of the cops on the show are bad. While the A-Story of each episode invariably centers on Vic and the Strike Team, the B-Story usually depicts two honorable detectives, Holland “Dutch” Wagenbach and Claudette Wyms trying to solve homicides and make the city a better place.

In season 5, Vic is pulled from street duty, which means the relationships he built with local gangs is no longer of any use to the police.

And then, when Claudette sees senior leadership playing politics rather than doing their jobs, she delivers a rant.

Claudette says that crime is skyrocketing because resources have been cut and cops are too spooked to do their jobs. This is true, though the series heavily implies that another reason for crime spiking is that Vic and the Strike Team have been disbanded.

But the interim captain replies to Claudette that crime has declined.

She then explains that this is because citizens have stopped reporting crime because they know police won't do anything.

I listened to a screenwriting podcast that distinguished between two storytelling techniques: The literary and the dramatic.

Literary techniques involve meaning and subtext and symbolism. Viewers detect these elements, but the characters in the stories don’t.

In contrast, drama is about actions and consequences. Cause and effect. Events happen, not to make a point to us, but from what the characters do. With good dramas, you understand why characters do what they do, and can follow the chain of events that unfold from their actions.

Literary techniques underscore the distance between viewers and characters. Dramatic techniques attempt to close them.

You can see this with TV shows. Some episodes of The Sopranos go nowhere. They’re just Tony dealing with his family, his business, and his therapy. He doesn’t have a goal. There’s nothing propelling him from one thing to another. You see mafia families that don’t want to go to war, and an FBI that isn’t in much of a hurry to build a case against them. Relatively little happens from season to season. There’s no MacGuffin. The Sopranos is literary (as is Mad Men).

On the other hand, in nearly every episode of Breaking Bad, people act, there are consequences, and as a result of those consequences, people respond and act again. Breaking Bad is dramatic (as is The Shield).

More people get immediately hooked on Breaking Bad than they do with The Sopranos.

The literary style is good at giving you a complete picture of a world. It can add in backstory, digressions, and even recipes (Moby-Dick contains an entire chapter about chowder) and still work. The literary style often uses flashbacks; the dramatic style uses them sparingly, if at all.

The Sopranos and Mad Men are full of flashbacks. The Shield and Breaking Bad contain very few.

Drama is about action. It’s about what people do. No matter how rich and complex your inner life and motivations are, you still have to choose, you still have to act, and you still have to experience the consequences (good or bad) of those actions.

That's why many rules of drama are about leaving things out. For example:

Start the story as late as possible

Start the scene as late as possible

Don’t have too many complications

Shawn Ryan (The Shield showrunner) has also referenced some of David Mamet’s guidelines when discussing how he approached The Shield.

-Don’t be boring. Mamet has written that “You, the writers, are in charge of making sure every scene is dramatic” and that audiences will “not tune in to watch information.” They tune in to watch drama.

-Every scene must advance the plot. Mamet: “The job of the dramatist is to make the audience wonder what happens next” and “The ability to do that is what separates [the writer] from the lesser species in their blue suits.”

The Sopranos is probably the best TV series of all time.

But that was largely because James Gandolfini as Tony Soprano is the greatest portrayal of any character in any medium. The plots were secondary to the viewer’s fascination with Tony. The Sopranos was a character study (which is literary by nature). It is driven by our interest in the protagonist.

In contrast, The Shield is primarily about plot and story. It is driven by our interest in what happens next.

Of course, the dramatic and literary styles are not neat categories and there is plenty of overlap. The best shows (including all of the ones mentioned in this essay) have both: Great characters and great plots.

But the distinction helps us to understand what a show prioritizes: Character or plot.

In The Sopranos, the main characters kill a lot of people, but never face any serious consequences.

The Shield, though, was relentless in its depiction of action and consequences.

The anchor of the entire show is that Vic murders a fellow cop, and this hangs over him for the entire series, all the way until the final episode.

As in real life, characters must deal with the consequences of external events and their own actions.

Paraphrasing Aristotle, Edward Teach (The Last Psychiatrist) wrote, “what shapes a person’s character isn’t his internal state, nor the sum total of his past experiences—though something like trauma may be relevant if it is used as something to overcome—character is formed by action only, and only in response to conflict. Literally nothing else matters.”

The Shield supplied a plot device that Breaking Bad would later employ to great acclaim: write the protagonist into impossible situations and see if you can find a way to write him out again. This gives both dramatic shows their “edge of your seat” quality. The Shield had an extraordinary and unrivaled ability to sustain narrative momentum, at least until its spiritual successor (Breaking Bad) came along. It was a perpetual motion machine.

You watch, step by step, someone make decisions and take actions that turn him into an evil man. And these are always choices. Vic (and Walt) intentionally, knowing full well the enormity of their decisions, choose to do the evil thing.

That’s part of what makes the shows so compelling.

The Shield continually poses an implicit question to the viewer: What are you willing to accept in exchange for a peaceful community?

At one point in the show, Vic is pulled off duty. Crime skyrockets in the city (this is when Claudette delivers her rant). Vic had the unique ability as well as the motive to make compromises, enter partnerships with criminals, and commit murder in exchange for profit and peace.

And he paid the price for it.

The Shield takes a classic view of character. It has no interest in their intrinsic “goodness” or “badness.” It has characters that have desires that they act on. And those actions give rise to good or bad outcomes. And the thing that makes you most who you are, the thing that's best about you, is what lifts you up. Or, in the case of The Shield, brings you down. Which is what makes the show a Shakespearean tragedy.

Vic’s greatest enemy turned out to be himself. He was so caught up in trying to obtain money for his family, amass a retirement fund, and cover up the many (many) crimes required to do that. He was constantly getting himself out of trouble, and temporarily freeing himself by making deals that then dug himself in even deeper than before. The way it all ends is incredible.

The television critic Alan Sepinwall has written:

“The Shield, whose ending was so powerful, so unflinching, and so very much a culmination of the entire series that it retroactively made everything that came before it better. Without that finale, The Shield is still a great show. With it, it’s one for the ages.”

The Shield is set in Los Angeles in the early 2000s, but the story is universal: Once upon a time, a man did a bad thing and thought he was still good; he got away with it, and lost everything else.

Hmm, the differences between literary and dramatic storytelling might explain why I loved The Wire and The Sopranos so much, but had trouble enjoying Breaking Bad. This also suggests that I might not enjoy The Shield. However, this is like the 3rd recommendation I've seen so it is time to go and check it out.

“I listened to a screenwriting podcast that distinguished between two storytelling techniques: The literary and the dramatic.

Literary techniques involve meaning and subtext and symbolism. Viewers detect these elements, but the characters in the stories don’t.

In contrast, drama is about actions and consequences. Cause and effect. Events happen, not to make a point to us, but from what the characters do. With good dramas, you understand why characters do what they do, and can follow the chain of events that unfold from their actions.

Literary techniques underscore the distance between viewers and characters. Dramatic techniques attempt to close them.”

Incredible review of the Shield 🍿 sounds great!

I enjoyed BB and Sopranos. Never saw the Wire.

Enjoyed learning about the literary vs the dramatic.

Have you watched and written a review of Oz (HBO MAX)?