I spent the last few weeks traveling throughout Southeast Asia.

This is my first time visiting this part of the world. I was in Kyrgyzstan (Central Asia) back in 2013, but that was for a deployment and I spent the entire time on a military base interacting only with fellow Americans.

Though I am half Korean by ancestry, I have no connection with Asian culture or heritage. It’s not an “identity” for me, in the same way that being American, or being a veteran, or being a former foster kid is.

I’ve only written one essay from the “Asian American perspective” and I felt a little bit like a fraud when I was approached to write it.

But then I remembered the strident and moronic activists who claim to speak on behalf of this group, yet have no real connection with it.

Upon reflection, I felt that despite my distance from the “Asian American experience,” I still had more in common with the typical working class person from that community struggling to get by than the status-seeking sociopaths (many of whom are actually ashamed of their parents and grandparents for not mindlessly obeying the latest ideological fashions) trying to co-opt and exploit that identity to advance their own social and material interests. You can read my essay about class and Asian American social mobility here.

A few years ago at Yale, a Korean student told me about her job interview, which consisted of a panel of three people. “I just wish one of them had been Asian,” she said. “I would have felt more comfortable.”

I have never once in my life had that thought, or anything remotely resembling it.

In America, the educated class is the most preoccupied with race and racial consciousness.

So much so that I have now absorbed some of their outlook. As I was traveling over the last few weeks, I registered the fact that the population in these countries look a lot like me, which is something I wouldn’t have cared about or perhaps even noticed seven or eight years ago.

Anyway, here’s an assortment of thoughts and observations about Malaysia and Singapore.

A Brief Overview of Malaysia (and Singapore)

Malaysia is known for, among other things, incredible food, ethnic diversity, political instability, and corruption. Generally, though, few westerners know anything about the country and its history.

Here’s an extremely brief history of Malaysia. With some discussion of Singapore too.

Malaysia was historically Buddhist and Hindu. After contact with Indian Muslim traders in the twelfth century, local rulers in Malaysia converted to Islam.

In the sixteenth century, Europeans were trotting across the globe in search of spices and other goods.

The Portuguese reached the Malay coast in 1509. They colonized the region and set up trading outposts.

To this day, some Malays still speak a dialect of Portuguese called Kristang.

Later, the Dutch wanted control of the spice trade. They formed an alliance with local sultans to oust the Portuguese. In 1641, Dutch and Johor (Malay) soldiers and sailors were successful in seizing control from the Portuguese.

Then the British developed an interest in the region. They needed a halfway base for East India Company ships on the India-China maritime route.

In 1824, the British and Dutch signed the Anglo-Dutch Treaty, dividing the region into two distinct spheres of influence.

So then the Dutch controlled what is now Indonesia. The British controlled what is now Malaysia and Singapore—then called “British Malaya.”

British colonial rule fundamentally altered the ethnic composition of Malaya.

They brought in Chinese and Indian migrant workers in part because they were useful as labor and because they held weaker nationalist grievances against the British colonial administration than local Malays.

These three ethnic groups form the bulk of modern Malaysia today:

Malays (today 62.5 percent of the population); mostly followers of Islam

Chinese (20.6 percent); primarily Buddhists

Indian (6.2 percent); generally followers of Hinduism

To be clear— “Malay” is an ethnic group. “Malaysian” is a nationality.

So you can be a “Malay Malaysian” or an “Indian Malaysian,” or a “Chinese Malaysian.”

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Chinese worked in mines and Indians tapped rubber trees and built the railways. This influx of labor revolutionized the Malayan economy.

But there was a growing resentment among Malays that the British were marginalizing them in their own country.

By the 1930s, many Malays were calling for independence from colonial rule.

In 1941, a few hours before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military landed on the northeast coast of Malaya.

In only a few months, they took over the entire peninsula and Singapore.

When I visited the National Museum of Singapore, I learned that the Japanese tried unsuccessfully to force everyone to learn Japanese before eventually giving up and using translators. However, they were successful in changing the local time zone by an hour and a half to match Japanese time.

The Japanese were brutal.

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of modern Singapore, has described his experiences as a young man, seeing the cruelty all around him:

“There was no human rights. The first thing I saw, two days after they came in, when I went out to sort of buy some food, were two human heads on a pole outside the tallest building in Singapore and Chinese characters to say ‘If you are not well-behaved, you will end up here.’ I thought to myself, ‘If only I had a camera.’ Here was this modern, 12-story building, highest in Singapore then, and this medieval scene. So the Japanese never talk of human rights because they understand the brutality, the cruelties that they inflicted on fellow Asians, whom they came to so-called ‘liberate.’ These are realities.”

And:

“The three and a half years of Japanese occupation were the most important of my life. They gave me vivid insights into the behavior of human beings and human societies, their motivations and impulses…I saw a whole social system crumble suddenly before an occupying army that was absolutely merciless.”

And:

“The dark ages had descended on us. It was brutal, cruel…One day the British were there, immovable, complete masters; next day, the Japanese, whom we derided, mocked as short, stunted people with short-sighted squint eyes.”

After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese surrendered and withdrew from Malaya and Singapore.

Older people in Malaysia and Singapore (as well as Korea and other Asian countries) still have some lingering animosity to the Japanese for their brutality during their imperial expansion in World War II.

I asked my girlfriend how her oldest family members would feel if I was half Japanese rather than half Korean. She said it would probably be fine. Probably.

I asked a friend from Seoul if young Koreans today are hostile to the Japanese. He said not really. But there is a subtle competitiveness in the Koreans when it comes to outperforming the Japanese economically. Perhaps a sublimation of the desire for revenge.

In the U.S., there is still a lot of guilt and anxiety around whether dropping the atom bombs on Japan was the right thing to do. But if you speak to the older generation in Singapore and Malaysia, who have memories of that era, they are grateful for America’s resolve.

After World War II, the Federation of Malaya achieved independence from the British colonial rule.

The federation was renamed “Malaysia” in 1963.

By the 1960s, the relatively poor Malays were growing resentful of the economic success of Chinese Malaysians.

And the Chinese Malaysians were resentful of the political privileges granted to Malays.

Chinese were generally treated as second-class citizens, despite their economic success (I am generally fascinated at how economic success does not necessarily translate to political power).

The Malay-dominated government then attempted to suppress all languages except Malay and introduced education policies that disregarded Chinese and Indian history, language, and culture.

It was around this time that ideological differences—notably government policies favoring Malays over other ethnic groups—led Lee Kuan Yew and his political allies to challenge the Malayan government, leading to Singapore’s expulsion from Malaya. Singapore, a small island just below Malaysia, became an independent sovereign country in 1965.

Some westerners think Singapore is part of China. Or used to be part of China. Or has some kind of connection with China similar to Taiwan or Hong Kong. This isn’t the case.

Singapore is mostly populated by the descendants of immigrants who fled China in search of work or to escape the strife of communism and political instability. But Singapore has never belonged to China or been a Chinese territory.

In 1969, in Malaysia, the Malay-dominated Alliance Party lost seats to the Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party.

Malays feared that they were losing political power.

This led to a full-scale riot. Hundreds of people were killed.

The brutality of the riots led to the Malaysian government enacting strict speech laws. And creating an affirmative action plan to help achieve economic parity between the Malays and Chinese.

Since then, Malaysia has managed to forge a tolerant and generally peaceful multicultural society (this is also true for Singapore).

Though they are the ethnic majority in Malaysia, Malays account for three in four of the poorest people in the country. Cronyism and discrimination against Chinese and Indians is widespread. Discrimination against ethnic minorities is an extremely sensitive topic in Malaysia. My girlfriend’s uncle advised me not to write about it.

Ethnic loyalties remain strong. The concept of a single “Malaysian” national identity is tenuous though much discussed in the country.

In contrast, in Singapore, the Singaporean national identity is strong. Regardless of ethnic background, people will generally tell you they are Singaporean first. The country requires compulsory military service for men, the children learn the national anthem, and schools cultivate pride in students by teaching them the history and culture of Singapore. Lee Kuan Yew was well aware of the dangers of attempting to forge a multiethnic nation, and had witnessed race riots firsthand. So he consciously set out to forge a unified, superordinate identity for Singaporeans.

Interlude on Free Speech

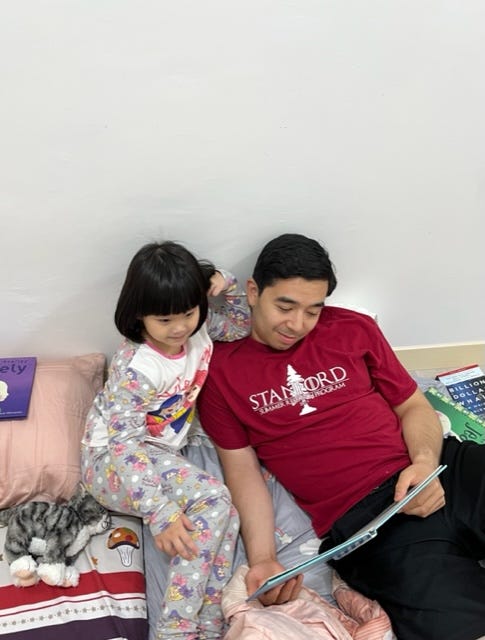

When I first began dating my girlfriend, who is Malaysian Chinese (her ancestry is ethnically Chinese, but her family has been in Malaysia for a couple of generations), she and I had a conversation that has lingered in my mind.

I described the importance many Americans place on freedom of speech. I spoke about how the interchange of ideas leads to truth, insights, efficiency, and a host of other benefits.

She then replied that if freedom of speech existed in Malaysia, it would rapidly descend into violence.

“Why?” I asked. My belief was that the suppression of speech was more likely to give rise to conflict.

“There’s a history of inter-ethnic violence and race riots. The strict speech laws against disparaging race, culture, or religion maintain peace.”

I listened to her explain the situation in Malaysia. I read about the history and politics of the region. My intuitions were pushed around quite a bit.

Gradually, I came to accept that each culture has its own set of values. And that the enlightenment ideal of the free exchange of ideas is very much rooted in a western mode of thinking. Each society is distinct in its development and ethics.

An adaptive and useful norm in one culture may have debilitating effects in another. One size does not fit all.

If one society has a long cultural history of free expression, then meddling with that norm might be foolish. If another society has a long cultural history of suppression, then lifting it might not be ideal.

The unwillingness to interfere with other cultures is something left-wing anti-imperialists and Burkean conservatives have in common.

The Oxford philosopher Isaiah Berlin, discussing the ideas of eighteenth century philosopher Justus Möser, has written:

“There is a local reason for this or that institution that is not and cannot be universal. Möser maintained that societies and persons could be understood only by means of a total impression, not by isolation of element from element in the manner of analytical chemists; this, he tells us, is what Voltaire had not grasped when he mocked the fact that a law which applied in one German village was contradicted by another in a neighbouring one: it is by such rich variety, founded upon ancient, unbroken tradition, that the tyrannies of uniform systems, such as those of Louis XIV or Frederick the Great, were avoided; it is thus that freedoms were preserved.”

An interesting aspect of western culture is what Berlin has called “monism.” The idea that there is one true way that humanity should live. The enlightenment is one example of this; the view that moral questions can be solved by scientific means, and that the answers arrived at by such a process must necessarily hold across time and cultures. Monism dates back before that, with Christianity. Whether “civilizing” other cultures, converting other people to Christianity, exporting democracy, installing handpicked political leaders and so on, there exists a strong desire to enforce a moral vision on other people.

Other observations and reflections:

I asked my girlfriend’s parents how their ancestors came to settle in Malaysia. They said their grandparents fled China in the early twentieth century. They cited poverty, political instability, and communism in China. But they didn’t know specific details, like the age of their grandparents upon arrival, what years they left China, and so on. It reminded me of Americans who have some vague awareness of their ancestors coming to Ellis Island, but have lost touch with the specifics of their family’s immigration history.

In Singapore and Malaysia I saw several young people give up their seats on the train for elderly people. I saw an old man give up his seat for an older man. Can't remember the last time I saw anything like that in the US or UK.

The Islamic prayer is broadcast publicly throughout Malaysia five times per day. My girlfriend’s family lives in a Buddhist Chinese ethnic enclave, yet the Islamic prayer calls are played loudly throughout the neighborhood. This woke me up several times in the night, but the residents in the neighborhood have learned to ignore it.

We walked around a village in Kedah where my girlfriend grew up. It was striking to see nice renovated homes right alongside dilapidated ones. This is in part because people here seem to be more grouped by ethnicity than income. So ethnic enclaves contain both middle class and lower class families. These two houses were literally side-by-side:

We went to some food stalls in a small Malaysian village and I learned that this is what they think of as “Western food”:

This reminded me of when you visit Asian restaurants in small towns in America. They’ll have bastardized menu items with names like “Chinese noodles” or “Shanghai beef.” I think this is less common now than it was 15 or 20 years ago, though.

Many ethnic Chinese no longer know the history of their ancestors’ journey to Malaysia. But they have been politically marginalized, and Malaysian schools are often de facto segregated by ethnicity, so the Chinese community in Malaysia primarily speak Mandarin (or Hokkien or other regional dialects from China). The absence of assimilation has preserved their culture. So much so that Chinese Malaysians are in many ways more “Chinese” than mainlanders in terms of culture. They have retained much of the traditional culture.

Chinese Malaysians are still practitioners of Buddhism and devotees of Taoism and Confucianism. This is in contrast to mainland Chinese who, as a result of Mao Zedong’s campaign against religion, have lost much of their religious and cultural heritage. Nevertheless, Chinese Malaysians also learn Malay in school, and the younger generation can speak English.

In contrast, Singaporeans primarily speak English. The young generation is losing their mother tongue. My girlfriend has family in Singapore, and her nieces in Singapore aged 9 and 14 did not know how to speak Mandarin or Hokkien. Only English.

On a flight, my girlfriend and I sat next to a large Chinese man (from the mainland). He kept slapping his stomach and shouting at the flight attendants how hungry he was. I told this story to my girlfriend’s father, and he said mainland Chinese with money often behave in an undignified manner. My girlfriend said this is because of Mao, who dismantled the decorum in traditional Chinese culture and didn’t replace it with anything. This might be an aspect of the vulgar Marxist view that religion, tradition, and manners are distractions from materialist concerns. My view is that the reverse is often the case; materialist concerns are often a distraction from the edifying benefits of ritual, tradition, and so on.

Relatedly, many people are familiar with Singapore’s peculiar laws. They have banned chewing gum and spitting, and enforce strict laws regarding littering. Apparently in China, litter and spitting used to be (and to some extent still are, in places like Beijing) widespread. In Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew enacted a campaign against spitting, and the Singaporean government began fining people for spitting in the 1980s. Lee wanted to create a cultivated, refined society, to attract business and establish Singapore as a First World oasis among developing countries in Southeast Asia. To do this, he forced people to shed what he viewed as the crass habits of the mainland.

LKY was strident and unapologetic in his view that ordinary people need moral leadership. The western media would often call him an authoritarian, and he would brush it aside. Here’s one of his quotes:

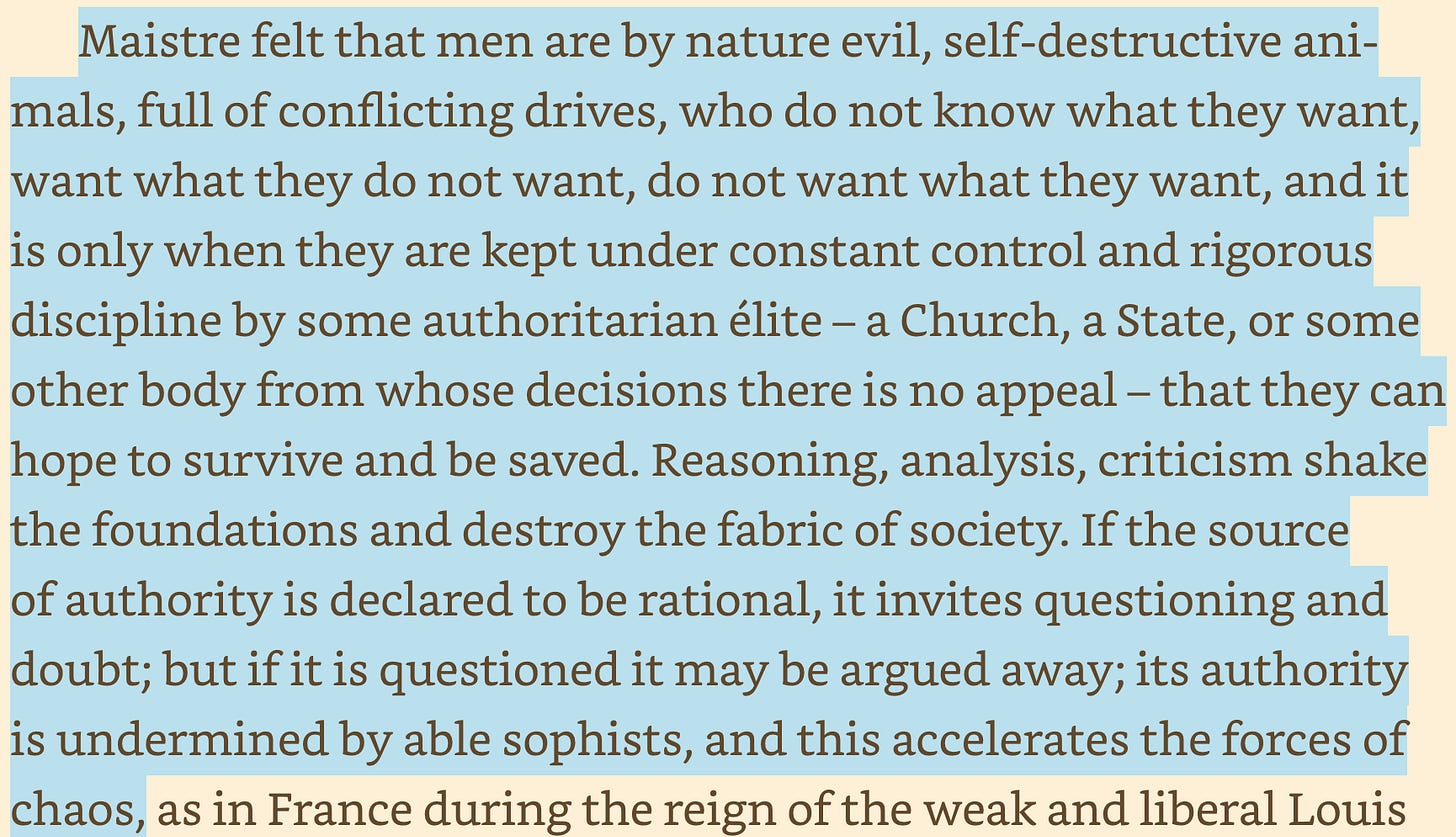

To some extent, LKY’s views overlapped with the philosopher Joseph de Maistre (1753-1821):

When I asked Chinese Malaysians if they feel more Chinese or more Malaysian, they say they feel more Chinese. When I ask Chinese Singaporeans if they feel more Chinese or more Singaporean, they say they feel Singaporean.

In Singapore I asked someone if the tap water is safe. He replied "yeah we drank it when I had to do mandatory national service." Then I remembered in the Air Force we filled our canteens in an outdoor bathroom/latrine tap right next to the toilets. As a kid mowing lawns and cleaning gutters I drank water straight from a rubber hose. Now I have a brita filter at home. Can't believe how soft I've become.

The older generation of Malaysians and Singaporeans don’t express much affection. Instead, they show it by trying to feed you. A lot. All the time.

My girlfriend’s elderly uncle told me that Malaysia and Thailand should be far wealthier than they are because of their abundance of natural resources. I asked why he thinks Malaysia and Thailand aren’t richer, and he replied “corruption.” He then observed that Singapore and Japan have few natural resources yet are rich because they have trust and are not corrupt. This man grew up in extreme poverty but was clearly intelligent and spoke fluent English, which is rare among elderly Malaysians who did not attend university. He stressed how poor he was as a boy and how proud he was of his children and his niece (my girlfriend). I thought of how much the world has changed—in the past a smart guy couldn’t leave his life behind, attend university, and enter a new social strata. Today, they can. While I am in favor of people improving their lives, much is lost when smart people leave their old communities behind.

We visited Thailand for a couple days. I learned that despite many Thai restaurants in western countries offering chopsticks to patrons, forks and spoons are more commonly used in Thailand. It is considered uncouth to eat from the fork (similar to how westerners view eating off a knife). The fork is used to push food onto the spoon, which you then use to eat.

I hired a local Malay tour guide to show me around Kuala Lumpur. He asked me “Why do white people eat rice with a fork? You can add way more onto a spoon.” He also said that Malaysians brush their teeth first thing in the morning, and then eat breakfast. And then explained that once he learned that westerners frequently eat first, then brush, he adopted that habit. His mom saw him do this and said, “Why are you behaving like the whites?”

Masks are pervasive. Indoors. Outdoors. In cars. People sitting outside by themselves. My girlfriend and I were frequently the only ones not wearing masks.

In Malaysia and Singapore, a common descriptor for white people is "ang mo kow." Directly translated it means "red-haired devil." Sometimes they use the softer term “ang mo kow” which means “red-haired monkey.”

Most of the books in bookstores in Malaysia and Singapore are wrapped in plastic.

Young upwardly mobile Chinese Malaysians often move to Singapore. Many of my girlfriend’s cousins live there. Her cousins told me the lack of natural resources has motivated Singapore to do all it can to attract and cultivate human capital because that’s the only way it can maintain its high standards.

My girlfriend tells me that her village in Malaysia is more run down than it was when she was a kid. Brain drain is a major factor. The population is aging, buildings are more dilapidated, fewer children and young adults live in the village compared to 15-20 years ago. Talented and ambitious young Malaysians who attend university subsequently relocate to Singapore, or Hong Kong, or Australia, or the US or UK. Similar to my observations of my hometown in California and other poor regions in the U.S., where smart young people tend to flee to metropolitan areas in search of economic, social, and romantic opportunities. Ease of geographic mobility seems to increase inequality.

The difference between Singapore and Malaysia is stark. They started in the same place when Singapore was expelled from Malaysia in the 1960s, but today Singapore’s GDP per capita is five or six times higher. It shows. Singapore looks like something out of a futuristic movie set in 2047 and Kuala Lumpur (Malaysian capital) looks similar to Bangkok

In the U.S. a few months ago, I spoke with an editor of a major outlet and she told me Malaysia is a better place to live than Singapore (because Singapore is too authoritarian). The Malaysians I spoke with told me Singapore is a better place to live (because Malaysia is too corrupt and chaotic).

Singapore’s demographics:

Ethnic Chinese (75.9 percent)

Malays (15 percent)

Indians (7.5 percent)

In Malaysia, Malays are the dominant group and Chinese are the sizable minority; in Singapore the reverse is true.

Though today it is majority Chinese, many Singaporeans—especially the younger generation—do not speak Mandarin or any dialect from China. They only speak English, and it is common for young Singaporeans to have no interest in their mother tongue.

The inequality in Malaysia is starker than anything I have seen in western countries. In Kuala Lumpur you’ll see a modern skyscraper and sleek shopping malls and two blocks over see people living in slums and serving food out of dilapidated stalls.

The poverty is on another level too. Many houses have battered and worn down cement flooring. No carpet, no hardwood, no ceramic tiles. Just cement. At the same time, though, social capital is high. Neighbors all know each other and regularly drop by to hang out with one another. People deliver food to other houses. Kids take care of elderly neighbors. There’s a boy who lives next door to my girlfriend’s elderly aunt and uncle who helps take care of them. I gave his parents a red envelope full of cash to give to him.

In his autobiography Undisputed Truth, Mike Tyson talks about the poverty he experienced as a kid raised by a single mom in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Then, when he became heavyweight champion, he visited Mexico and saw poverty unlike anything he’d seen before. He grew up wearing old shoes. The kids he saw in Mexico had no shoes at all. That story came to mind as I compared my upbringing in the U.S. with the Malaysian villages.

I asked a Malaysian in Kuala Lumpur for restaurant recommendations and he explained that the prices in the city range literally from $1 to $300 USD for a good meal. I had many meals of the former type (the food stalls in the country are, as a rule, excellent) and one of the latter type (check out Dewakan in Kuala Lumpur).

When you land in Singapore, you hear the flight attendants announce that smuggling drugs into the country carries the death penalty. Lee Kuan Yew has said “If we could kill drug dealers a hundred times, we would, because you destroy whole families. You steal. You cheat. You rob your own parents. It's soul-destroying.” When LKY was a child, one in four Chinese adults in Singapore were addicted to opium. Today, drugs in Singapore are practically nonexistent.

After about a week in Singapore, it occurred to me that I heard zero ambulance or police sirens.

In both Malaysia and Singapore, it is illegal to disparage anyone for their ethnicity, culture, or religion. Laws were enacted after the brutality of the race riots in the 1960s.

The poorest person I spoke with on my trip (an elderly Chinese Malaysian man who catches frogs and cooks noodles to support his family) and the richest person (tech entrepreneur) both told me that Singapore is an incredible place; a sort of promised land.

It’s customary to call anyone middle aged and above “uncle” or “auntie.” This was a huge help for me as someone who is bad at remembering names.

I was curious about the intricacies of this and asked my girlfriend when it applies—in Korea too? Yes. Indonesia? Yes. What about Asian American middle aged men and women—would you call them uncle or auntie? No, she told me, because they have been indoctrinated to resist being thought of as “old.” This may be because in Asian cultures the elderly are venerated, and in the U.S. it is youth that is glorified.

My old suitcase (after 7 years) has taken quite a bit of damage so I bought a new one. My girlfriend gave my old suitcase to an Indonesian woman who works for her parents. I used to carry my belongings in garbage bags as a foster kid, but I still felt sympathy for this woman when she asked to have my old suitcase.

It’s difficult to judge social class in a different culture. But families in Malaysia are stable regardless of socioeconomic status. My girlfriend’s parents have a decent house. They have been married for more than three decades. They run a restaurant and work hard. Both of their children went to university and moved out of their hometown, but both are loyal to their parents and want to ensure their comfort as they enter old age. Social ties are strong in Malaysia. Poor families are remarkably stable, despite having far less in the way of material resources than the poor in the U.S. or the U.K. In contrast, parents in the U.S. are raising kids who don’t like them very much and many will not be devoted to them in old age.

In a Thai restaurant I asked for a glass of water and they gave me a rice (or maybe it was barley) flavored beverage. When they gave me the glass, I apologized and asked for water, and they gave me another rice-flavored beverage. I gave up and bought a bottle of water. I’ve already been bloated from all the good food here, so I’m trying to avoid drinking carbs.

Although the Chinese ethnic minority are overrepresented among the Malaysian business elite, they don’t seem to have been able to convert their economic capital into political power. The Malays dominate the political sphere, despite not having the same level of financial resources as the Chinese. Reminds me of how little political power the tech sector in the U.S. has, relative to its material wealth. More generally, it leads me to wonder just how much money actually matters when it comes to political power.

Many food stalls and restaurants in Malaysia don’t offer napkins. You have to bring your own tissues.

Singapore is a country where its plumbing systems have kept pace with its advanced economic development. Malaysia is a different story.

Speaking only English with no ability to communicate in any other language seems to be viewed as posh (if you are Asian), and speaking English with an American or British accent is also considered tasteful or refined. Speaking English well is generally a marker of education and wealth.

All I knew about Singaporean English is from the movie Crazy Rich Asians, in which the main characters speak with either a British or American accent. But most Singaporeans speak with their own distinct accent.

Relatedly, we watched the Lee Kuan Yew musical in Singapore. I learned that LKY grew up in a middle-class family speaking mostly English. He attended Cambridge on scholarship. He took Mandarin (as well as Malay and Hokkien) lessons as an adult to bolster support among different political constituencies. The play makes a big deal out of the fact that he was unable to speak Mandarin. Today, English is the national language of Singapore, which is a key reason it has attracted so much business, propelling its miraculous economic growth.

This was super interesting!

About the whole free speech thing—it’s interesting your girlfriend would say that. I was researching and just wrote about how in the French Revolution King Louis XVI enacted free speech laws that brought the number of news publications and periodicals up from about half a dozen to over 1,300 during the course of the revolution. People were both free to say what they wanted but also had an over abundance of information and didn’t necessarily practice the best or most ethical judgement when publishing their papers. Free speech is great, but on the flip side of that coin, chaos can ensue.

I also think it’s interesting that you picked up on the importance of family structures in poorer countries. The breakdown of the family in the US is probably the biggest tragedy of the last century, and the impact will be felt for a long time.

Very interesting! I have been thinking of visiting that area, this definitely makes me more interested in doing so.

I have also heard that Lee Kuan Yew has an excellent biography. I'll have to check it out, he sounds quite wise.

I really dislike the sentiment of 'I wish there were more people like me', meaning people who look like me. It's so shallow. I'm not supposed to say that obviously as a white guy, supposedly i'm blessed to be around people who look like me. Which was the case in my white hometown, although once you go to college and a bigger city it isn't the case nearly so much. And it doesn't make a difference, for the most part the worst people i've known in my life have been white. You might expect that since i've been around so many white people. But my feeling has always been that it just matters how you act and carry yourself. Here in the west it seems like we have an elite class intent on making it all about shallow things like skin color, and not allowing us to move past that. They'd say that isn't possible. A depressing mindset. Why would you want multiculturalism if you don't think people can't move past something like that. But I digress.