Two recent studies led by Harvard economist Raj Chetty found that having well-off friends as a kid improves your odds of making more money later in life.

The researchers analyzed more than 70 million Facebook users and their friendships to explore how social relationships are associated with social mobility.

They ranked users by socioeconomic status, age, and zip code, among other variables.

A key conclusion is that geographic locations with more ties between low and high-income individuals also have higher rates of upward mobility for lower-income people.

On average, a low-income kid who relocates to a community with more economic connectedness (more cross-class relationships) will have a 20 percent higher income as an adult.

The findings suggest that if a poor child grows up in a neighborhood where 70 percent of their friends are wealthy—the typical rate for higher-income children—then their future income would rise on average by 20 percent.

This is roughly equivalent to the difference between having a high school diploma and a college degree.

Part of this, of course, is because having high-income friends increases the likelihood that you yourself will apply to college.

The focus, naturally, is on future earnings. I would be curious to know if poor kids in a predominately wealthy neighborhood or school go on to be happier.

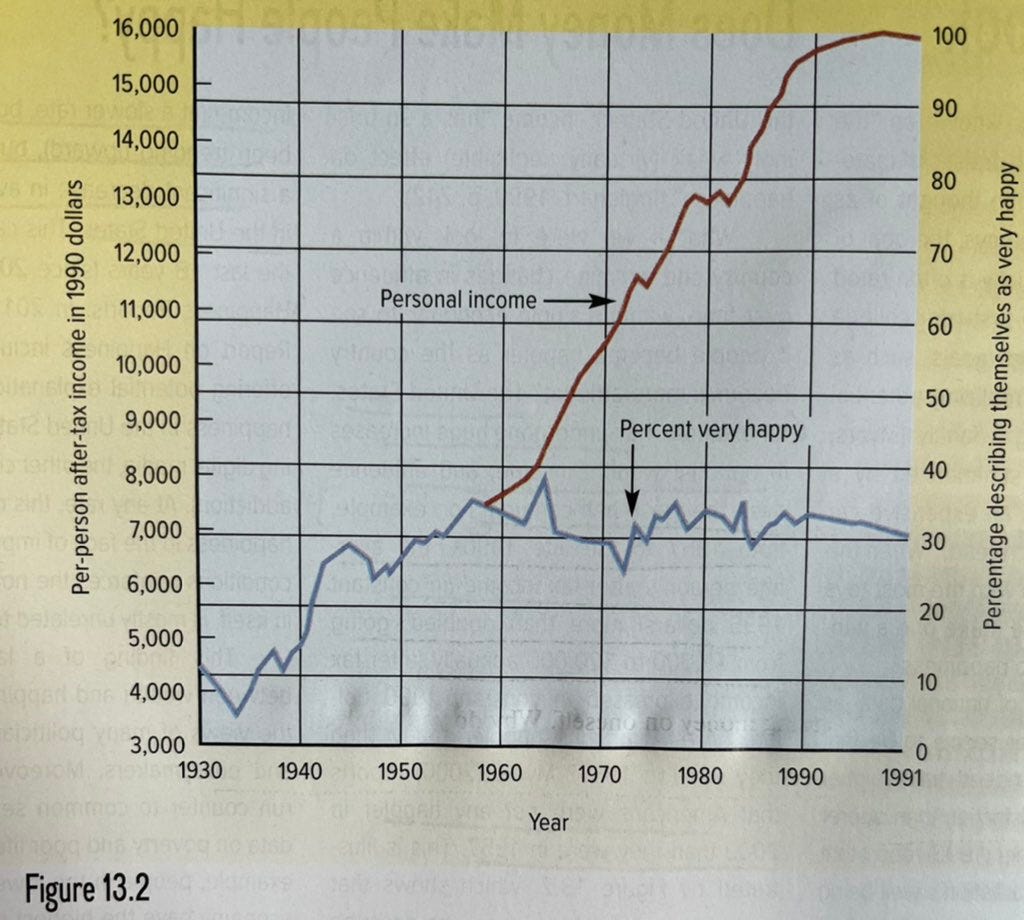

Assuming happiness (rather than individual achievement or measures of upward mobility) is the actual aim of public policy, it’s worth noting that as income in the U.S. soared from the 1940s to the 1990s, Americans’ level of happiness remained the same:

In his recent book Don’t Trust Your Gut, data scientist Seth Stephens-Davidowitz reports research indicating that beyond the point at which people can afford basic material needs, the link between money and happiness is tenuous:

“One reason that we aren't getting any happier even though we are getting richer is that money has only a small effect on happiness...Doubling your income can be expected to increase your happiness by about one-tenth of a standard deviation.”

Interestingly, Chetty and his colleagues discovered a “friending bias.” The finding is that even when low-income and high-income kids interact with one another, they tend not to become friends.

In fact, even if economic divides were eliminated and every zip code, every school, and every college in America were perfectly balanced by income, the researchers found that 50 percent of the current social disconnect would remain between the rich and the poor as a result of this friending bias.

Which makes sense.

Rich people prefer to be around rich people. And poor people, believe it or not, often don’t enjoy being around rich people very much. People generally favor being around people like themselves.

Including me.

I still keep in touch with a couple of friends from high school. But the more time passes, the harder it gets. Our life trajectories have completely diverged.

But most people in my friend group today were not born into fortunate circumstances, either. When I’m around people from comfortable backgrounds, I understand it’s not their fault that they didn’t have to endure the same kind of struggles that the guys I grew up around did. I sometimes find it hard, though, to fully connect with them. Weirdly, I’ve found that I get along better with people who grew up rich and don’t apologize for it than upper middle-class people who pretend to be poor out of an obnoxious sense of guilt.

Unsurprisingly, the people I’m most comfortable around are those who, like me, started with relatively little and found a way to improve their circumstances. This is a small pool—smaller than the groups of people who start out and remain either poor or rich.

Yet this is my “friending bias.”

Something overlooked in discussions of class acculturation for upwardly mobile people is how difficult it is to maintain ties with friends across multiple classes.

A study investigated how social relationships influence newspaper-reading habits.

The paper found that a highly educated professional has a 57 percent probability of reading prestige newspapers (“broadsheets”) if their best friend is also an educated professional.

But if their best friend is a blue-collar laborer, then the probability drops to 32 percent.

Not reading prestige newspapers, though, impedes upward mobility. Lacking awareness of the etiquette and concerns of the educated classes can impede success in white-collar occupations.

So if an upwardly mobile working-class person maintains ties with old friends, and retains some of the same cultural habits, it will become harder for them to integrate into a new class.

How many low-income people want to lose contact with their old friends for a shot at upward mobility? Very few. If I had known in advance that this would happen, however gradually, I may have made different choices. I felt a deep bond with my friends growing up, and still do, even as the distance between us grows.

In his recent book Friends: Understanding the Power of Our Most Important Relationships, the Oxford psychologist Robin Dunbar writes:

“Special friendships are very few in number…the ones with whom we shared the ups and downs and traumas of early adult life, whose advice we sought in those moments of deep crisis, the ones we sat up with late into the night…It’s as though this small number of special friendships are carved in stone into our psyches precisely because we engaged in such intense, emotionally passionate interactions. We can pick up these relationships years later exactly where we left them off. But for the rest, friendships are fickle things.”

I have friends who I haven’t spoken to for years. But if and when we speak again, we will pick up right where we left off.

Other research indicates that in terms of the effect on happiness, having a friend you see regularly is equivalent to making an extra $100,000 a year.

Assuming it is harder to form deep friendships with those very different from ourselves (which seems undeniable in the case of rich and poor kids), would it be wise to introduce policies that would reduce the likelihood of deep friendships developing so that low-income kids can earn a 20 percent higher income later in their lives?

In NPR’s coverage of these studies, they report that “cultivating these kinds of relationships is crucial for upward mobility in America.”

But where does the drive to cultivate them come from?

It’s hard enough to make friends with people who are similar to ourselves. Building relationships with people who are very different is even more demanding.

I was reminded of this rant from a couple years ago:

“Let me tell you something. We get fed a steady diet of ‘If these people just had some opportunity’ or ‘If they were afforded the same or ‘If they were given the chance to excel, they would grab the American dream…’ BULL FUCKING SHIT. I’ve had A THOUSAND conversations with A THOUSAND losers where I went “Listen to me. Let me help you!” Then I get “Fuck you, fuck off, talk to the hand.” This fucking notion of ‘oh these poor people, they’re so noble and all they want is a chance.’ Are you fucking nuts? Everyone I tried to help from my old neighborhood has told me to fuck myself. Every one of them! All poor. All losers. All making the same goddamn mistakes over and over again refuse my help out of some insane sense of pride. Like opportunity is a stick of kryptonite to these people if they were superman. They do everything they can to avoid it. They get all puffed up and tell me how they roll and what they do and their plan and how I’m not the boss of them. The idea that they just need a helping hand. That is something we have signed off on, like as a society. No goddamn way. In my experience, almost everybody I have extended a helping hand to and went ‘Here’s what we can do has actually treated me worse than when I was just a loser like them. They are horrible. None of them take your advice, none of them say thank you, and no one takes opportunities. I’m not even just talking about poor people. Another friend of mine went to fuckin’ UCLA and Berkeley and I told him to come be a writer on my new TV show and he just replied that he’ll come up with his own thing. The same thing he’s said for the last five fuckin’ years. Then asks if he could borrow one of my cars for a date. Fuck these people.”

-Adam Carolla (comedian and former construction worker)

Carolla is one of the rare successful comedians today who grew up poor, worked blue-collar jobs, and still maintains ties with the guys he grew up around.

Making good choices is hard enough, even in the best of circumstances. Just because you know something will benefit you, doesn’t mean you’ll actually do it. Back when I was a kid who barely graduated high school, I knew a lot of the choices I was making in the moment were unwise. I just didn’t care.

Carolla’s rant reminded me of experiences I’ve had trying to help my friends. A couple of examples come immediately to mind.

When we were both nineteen, one of my high school friends (raised by his grandmother because his mom was addicted to drugs and his dad was in prison) worked ten hours a week at Burger King. Our other friends and I mocked him endlessly for having to wear a visor at work.

He’d also make fun of me, reminding me that only three years prior, I had to wear an apron to work in my dishwashing job.

We were at Applebee’s one day. I saw a sign out front that said they were looking for full time servers. I told my friend to ask for an application. He replied in a mocking tone, “You ask for an application.” I got up to use the restroom and picked up an application on the way back. Right there in the restaurant we filled out the application for him together.

They hired him. When he was scheduled to start his first day on the job, he simply didn’t show up.

Another story.

Five years after my friend ditched his Applebee’s job, I had just finished attending the Warrior-Scholar Project, an “academic boot camp” designed to help veterans prepare for college.

I returned to my unit after completing the program. I told everyone I knew about it. I told them I’d help them with their applications after work if they were interested. Zero people took me up on my offer. The same thing happened when I got my acceptance letters for college. I told all the junior enlisted guys that I would be happy to help with college applications. Three guys expressed interest. I followed up with them as the deadline approached, and each said they were no longer interested.

It took a few more experiences like this before I would finally learn an important lesson—people don’t like unsolicited advice. When someone is ready to change the direction of their life they will seek out guidance. But foisting advice on people doesn’t work.

People often ask me why I turned out differently than my friends. One major reason is that I was smart enough (or dumb enough) to enlist in the military. I didn’t fully realize what that decision would entail. Being locked in an environment where I was forced to follow all the rules; where my choices were stripped from me. It wasn’t, “Show up to work and if you don’t you’ll be fired” or “Do drugs and you might, maybe, someday, face unpleasant consequences.” It was “Show up for work, and if you don’t, you will be court-martialed” and “Don’t do drugs, and if you do, you will be court-martialed.” I had to spend years in that extremely rigid environment to shed bad habits.

Right around the time my enlistment concluded and I moved to New Haven, one of my high school friends joined in the military. I asked him what made him decide to enlist, and he replied, “You.” I didn’t tell him to, or advise him to. He simply saw it had benefited me, and wanted to experience those changes himself.

He may have doubled his earnings during that six year enlistment (cumulatively—in the first couple of years you basically make minimum wage, but then earnings increase quite a bit after that), which, interestingly, might have collectively raised the overall income of my high school friend group by 20 percent on average (which was a key finding in those new studies).

But after my friend left the military, he fell back into the same habits. Working a low-income job, smoking weed in parking lots, and trying to sleep with women much younger than himself.

In the aggregate, the Chetty study finds that having affluent friends helps low-income people earn more later in life.

But my guess—which is just a guess—is that there are some power laws at work here. It’s not that having rich friends lifts every poor person’s income by 20 percent. Rather, out of, say, 5 poor people who have some rich friends, 1 out of this 5 (who likely has some highly atypical characteristics) will go on to earn far more than he otherwise would have.

Anyway, these new studies are carefully done and help us to understand the factors underlying social mobility. Having rich friends improves your likelihood of earning more money later in life. Still, the implications for the real world are unclear. The burden of trying to befriend people with a totally different life experience might not be worth the future earnings premium.

I imagine someone making an offer to me as a kid.

“Hey, when you grow up do you want to make 20 percent more money than you otherwise would have?”

“Sure.”

“All you have to do is make friends with a bunch of rich kids.”

“No thanks.”

Great piece. This makes me think of Francis Fukuyama's book, not the famous one but a later one, whose thesis is about the demand for dignity. It talks about how dignity is at the core of who we are as people, and I think that's relevant here because there are many things that matter to people more than money. Money is I think overrated in our society, people act like it's the end all be all, but beyond a certain point it takes a backseat to other factors. As your writing here points out.

I also find this to be the case in a lesser topic which is when recommending things like books, tv shows, or movies to people. Most people like to find things out for themselves.

In my years of drug abuse I spent a lot of time around poor people, and I realized just how much differently they live their lives. One experience in particular really shocked me.

I was hanging around (likely waiting to score drugs) and I ran into some teenage kids. Somebody told them I had a job, and suddenly I turned into the most interesting person in the room. The kids were very surprised by this information, and asked me a lot of questions about how one goes and gets a job.

It occurred to me that these kids didn't have a single role model in their life - all the adults they knew were drug-addicted losers; people looking for government handouts to finance their lives of doing nothing but drugs.

Poverty is such a complex set of incentives, culture, and behavior.