A Prize To Be Won By Fierce Struggle

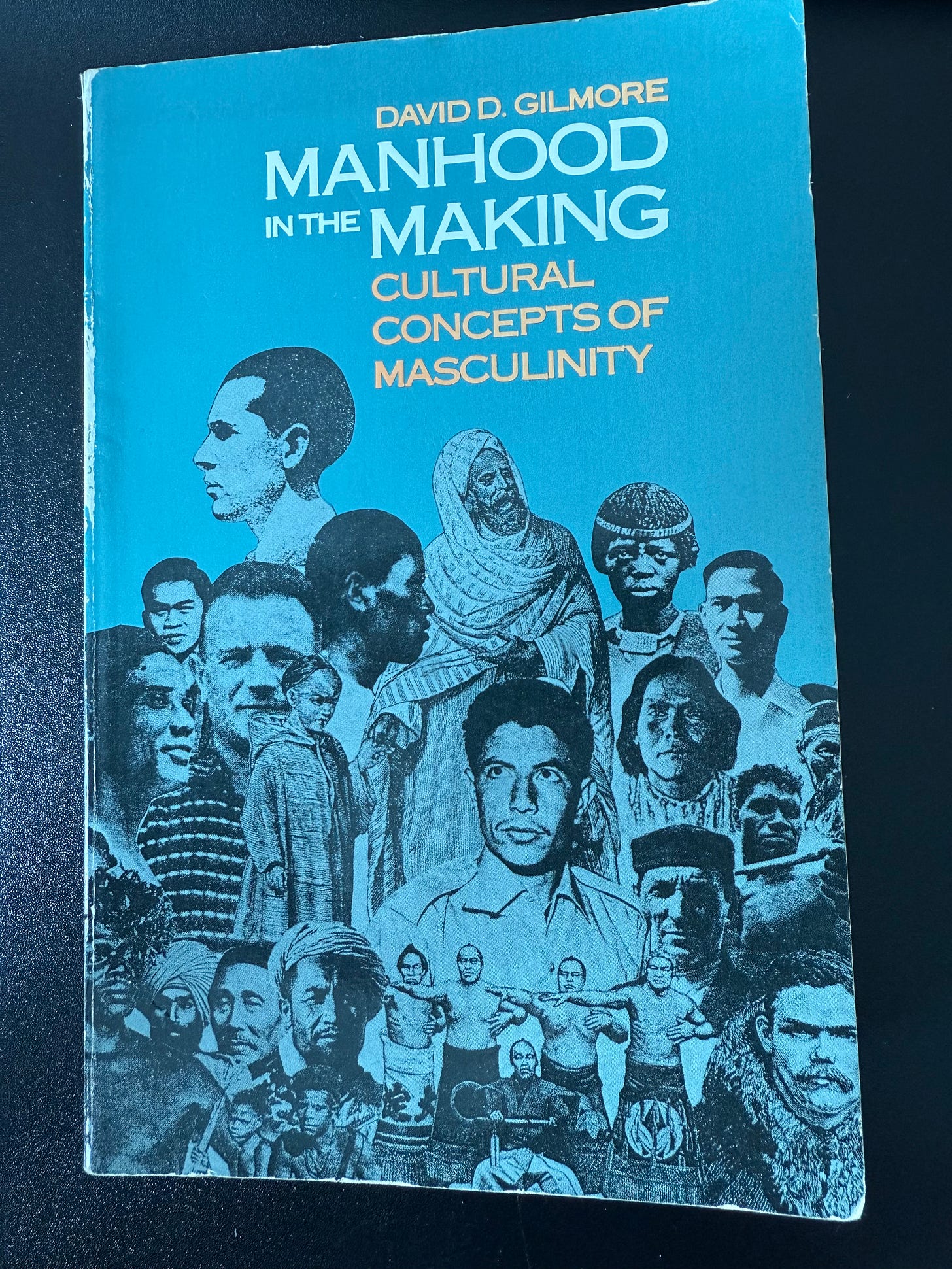

Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity — A review

After years of living in foster homes, I was adopted by a woman who got a divorce — which was followed by a string of catastrophes in our lives. Then my adoptive mom entered a relationship with a woman named Shelly. When I was in eighth grade, they figured out that heating a house with firewood was cheaper than using the central heating system.

That winter, I woke up at 5:30 a.m. every day to light a fire so the house would be warm by the time my moms got up for work. At first I objected to this new chore, complaining that it wasn’t fair. My mom and Shelly calmly explained that they worked all day to pay the bills, and keeping the house warm was the least I could do as “the man of the house.”

At age 13, this was the first time anyone had ever described me as a “man.” I implicitly grasped that it had something to do with responsibility and contribution.

Depending on where they fall politically, many people believe, hope, or fear that men are “naturally” ambitious, confrontational, risk-seeking, and other male-coded attributes. Until recently, I believed this myself.

But recently I read “Manhood in the Making,” a 1991 book by the anthropologist David Gilmore. It changed my mind. Gilmore argues that masculinity isn’t something that just happens to boys as they grow up. Cultures had to create manhood — had to actively train it into young men — because the natural state of young males is apathy, self-indulgence, and laziness.

Indeed, many young men today don’t seem like they’re bursting with disruptive energy. They seem checked out. Detached. Coasting through life.

Now, many are told that manhood is just a social construct. And, as Gilmore points out in his fascinating book, it is. But it is a useful one.

Social constructivism has gotten a bad rap in recent years, mostly because of how it’s been used and misused in debates about sex and gender identity. That’s unfortunate, because when it’s done properly, constructivist thinking can offer important insights about how the world actually works.

The philosopher Joseph Heath has observed that many progressive academics are drawn to constructivism because they’re frustrated by certain aspects of society but also recognize there’s no use criticizing something that can’t be changed. If a particular social arrangement is a construct, then maybe it can be changed, and so it becomes worth criticizing.

The problem is, people sometimes take this logic too far. They start declaring things to be social constructs simply because they wish they were different. For example, some argue that biological sex itself is purely a social construct — not because there’s strong evidence against sex differences, but because redefining sex as entirely socially constructed would support political goals regarding gender equality or identity.

But many people also make the opposite mistake. They assume the social world around them is natural, fixed, and inevitable. They forget that many of the things they take for granted are actually constructs. Anyone who spends time reading history or studying other societies eventually sees this. Other people in other places have lived by very different rules.

That’s what Gilmore’s book helped clarify for me. Manhood is not a biological fact. It’s a social role, built around expectations and obligations. Being male is biological, but in cultures all over the world and throughout history, manhood has been a title — a status one must earn.

There’s a scene in the 1999 cult classic film “Office Space” where the protagonist is asked what he’d do if he had a million dollars. After a few crude jokes, he pauses and says, “Nothing. I would relax. I would sit on my ass all day. I would do nothing.”

Most men, particularly young men, would far prefer this mode of living as opposed to, say, being a domineering tyrant or a responsible authority figure.

Mature masculinity is artificially induced through culture. Mature men do not naturally emerge like butterflies from boyish cocoons. Rather, they must be carefully encouraged, nurtured, counseled, and prodded into taking the actions necessary to achieve mature manhood.

Gilmore writes, “Manhood is a cultural construct based on group needs that overlays and counteracts a hesitant and resisting nature.” In other words, manhood exists to push against the default setting: self-indulgence and avoidance of responsibility.

He also points out that work is typically viewed as “synonymous with suffering,” and “is something most men will freely admit they hate and would avoid if they could.”

Social conservatives often assume men naturally want to be good husbands and fathers. If that were true, ancient Rome wouldn’t have needed laws against bachelorhood. It took serious effort to get men to take on those roles. Progressives make a similar mistake, assuming men desire power and control. But most young men today aren’t power-hungry. They’re increasingly checked out.

This is why cultures around the world created rituals to shape boys into men. As the psychologist Roy Baumeister has written, “In many societies, any girl who grows up automatically becomes a woman.… Meanwhile, a boy does not automatically become a man, and instead is often required to prove himself, usually by passing stringent tests or producing more than he consumes.”

Gilmore points out that on the Greek Aegean island of Kalymnos, many of the inhabitants make their living by commercial sponge fishing. The men dive into deep water without the aid of special equipment, which they scorn. Diving this way is a gamble because many men are injured. Young divers who take precautions are mocked as effeminate and ridiculed by their peers.

Halfway around the world, in the high mountains of Melanesia, young boys undergo intense trials before achieving the status of manhood. Young boys are torn from their mothers and forced to undergo a series of brutal masculinizing rituals. These include whippings, beatings, and other forms of terror at the hands of older men, which the boys must endure stoically and silently. This community believes that without such hazing, boys will never mature into men but will remain weak and childlike. Real men are made, they insist, not born.

Many cultures, Gilmore writes, view manhood as “a prize to be won by fierce struggle.”

Perhaps my favorite manhood-related insult comes from Papua New Guinea. Men who are cultural contributors and creators are honored for their constructive manhood and are said to have “strong heads.” The object of shame is the man who “consumes more than he produces,” and thus “fails in all the constructive masculine pursuits: he provisions no one, cannot protect his kinsmen from attack, impregnates few women, and contributes little that is new and useful to the economy, religion, or technology,” Gilmore writes. This physically and culturally sterile man is said to have a “soft head” — like a baby.

Boys have to be encouraged—sometimes actually forced—by social sanctions to undertake efforts toward a culturally defined manhood, which by themselves they might not do.

To become a separate person the boy must first break the chain to his mother. His masculinity thus represents his separation from his mother and his entry into a new and independent social status recognized as distinct and opposite from hers.

The principal danger to boys is not the fear of the punishing father but a more ambivalent fantasy-fear about the mother. The ineradicable fantasy is to return to the “primal material symbiosis.” The comforting sense of omnipotence that this symbiotic unity with the mother affords. The blissful experience of oneness with the mother is what draws the boy back so powerfully toward childhood and away from the challenge of an autonomous manhood. Manhood is a “revolt against boyishness.”

The devouring mother can inhibit this, as Jordan Peterson and others have noted. The mother who refuses to allow her son to grow up is one source of “castration anxiety,” the fear of never developing into a man. Manhood imagery, Gilmore suggests, is “a defense against the eternal child within…against what is sometimes called the Peter Pan complex.”

The manhood ideology is a culturally conditioned defense against the wish to take “the path back to fusion with the mother and the pleasures of infancy.” Manhood is an “institutionalized countermythology” aimed at combating the desire for a blissful return to the mother. To be rescued from the hardship of life into a serene and primitive unity.

It is perhaps for this reason that in many cultures, there is “no greater fear among men than the loss of this personal autonomy to a dominant woman.” This anxiety is widespread, as I note here in a separate discussion of another of Gilmore’s works.

In Troubled I describe how during the summer before my senior year of high school, my mom and Shelly relocated to another city 4 hours away. I stayed behind, moving in with my best friend, who lived with his dad and brother. Shelly said “It might be good for you to live with some guys for a while.” Both Shelly and my mother had a working-class mindset that didn’t object to the idea that boys and girls are different. I am 100% certain that they would not have allowed my sister to do the equivalent of moving in with a female friend at such a young age. Perhaps leaving a 16 year old boy in such a situation isn’t a great idea. But, at least in my case, it was what I needed. A year later, I had to ask my adoptive mom to sign a special document to allow me to enlist at age 17. She was momentarily hesitant but didn’t require much convincing. I shipped out for basic training 6 weeks later. To this day I am grateful to her for this. I’m more distant from her than I’d like to be (and not in a geographic sense). Still, I prefer overly distant to an enmeshment that would have hindered my development.

In many societies, men who chose hardship in service of others were rewarded. They were given the title of man. With that came honor, status, and more opportunities to pass on their genes. Men who opted out, who sought comfort over challenge, were shamed. The desire for recognition from their community served as a powerful incentive.

Which might help explain why, in wealthy, modern societies, masculinity is now mocked or pathologized. In safe, prosperous environments, many question whether masculine strength was ever necessary at all.

There’s a common belief that men are naturally dangerous—aggressive, predatory, criminally inclined. And there’s some truth to that, but it’s more complicated than people think. Yes, at the far ends of the spectrum, there are more risk-taking and violent men than women. But that’s not the average. Men are, on the whole, slightly more adventurous, slightly more aggressive. The difference is real, but it’s not dramatic. The average man isn’t wildly different from the average woman when it comes to traits like courage, assertiveness, or even the tendency toward violence.

Interestingly, Gilmore goes so far as to say that “men are no more ‘naturally’ brave than woman are and that their risk-seeking response is counterphobic and culturally—rather than biologically—conditioned.” Counterphobic here means to intentionally seek out the object of your anxiety in order to overcome those anxious feelings. Presenting an image of strength even when internally you are ambivalent, anxious, or fearful. Manhood is the triumph over the natural impulse to flee from danger and responsibility.

So why do we picture men as so much more dangerous? Part of it is statistical. Men show greater variability in these traits, which means the worst offenders—violent criminals, serial abusers—are more likely to be male. That small group distorts our perception of the whole.

But there’s also psychology at play. We’re biased to remember extreme cases. Ask someone to picture a violent person, and they’ll likely think of a man. That’s availability bias. And because our brains are wired to prioritize threats, those impressions stick. That’s negativity bias.

This creates a strange paradox. The worst men — the true predators — need to be constrained. They need less boldness, less aggression, less entitlement. But the rest — the vast majority — need the opposite. They need encouragement. They need to be challenged to step up, take risks, and take responsibility.

The problem is, most public conversations don’t make this distinction. They flatten the male experience into one story. But blanket advice doesn’t work. A society that wants to flourish has to learn how to contain the worst men and cultivate the best ones.

Looking back, I realize my first real lesson in manhood didn’t come from a father figure or a traditional rite of passage. It came from two hardworking women trying to hold things together in a tough situation. When they called me the “man of the house,” they were challenging me to live up to a title that must be earned.

A version of this article was originally published by the Boston Globe under the title “‘A book that changed my mind: ‘Manhood in the Making.’”