Thomas Sowell, now 93 years old, is one of the most esteemed and prolific authors and social commentators today. Trained as an economist at Harvard and the University of Chicago, he has written more than thirty books, and from 1991 to 2016, he had a nationally syndicated column.

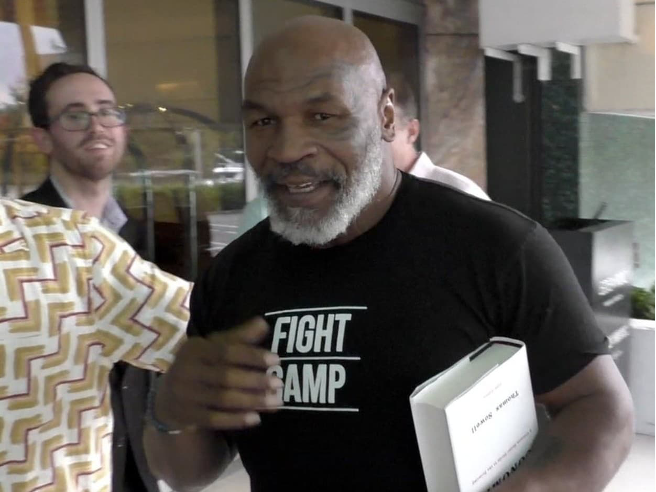

Sowell’s readers and admirers include the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker and the former heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson.

Pinker has characterized Sowell as the most underrated author in history. He also stated that, “Sowell is a libertarian conservative, which makes him taboo in mainstream intellectual circles, but even those who disagree are well advised to grasp his facts and arguments.”

Mike Tyson has been publicly spotted carrying a copy of Sowell’s book Basic Economics.

Thomas Sowell was a Marxist as a young man. Today, though, he is generally considered to be on the political right.

I recently read his memoir, A Personal Odyssey.

The entire book is superb. However, the sections that were most compelling for me cover his childhood, early life in poverty, teenage homelessness, experiences of being drafted into the Marine Corps, and financial struggles during his college and grad school years.

Here I’ll share some lessons from the book that stood out to me.

Not all of these lessons, of course, were learned for the first time.

Some of them I re-learned through the process of walking through life from Sowell’s point of view. Often, learning a lesson once isn’t enough. Lessons sometimes have to be reinforced. And frequently, a lesson has a stronger impact if it comes from the right person at the right time. Hearing a piece of hard-won wisdom from Thomas Sowell (or any other thinker you respect and admire) might hit you differently than hearing it from, say, your parents or a teacher.

“In retrospect, even my misfortunes were in some ways fortunate, for they taught me things that would be hard to understand otherwise, and they presented reality from an angle not given to those, among intellectuals especially, whose careers have followed a more straight-line path in familiar grooves. I lived through experiences which they can only theorize about.”

—Thomas Sowell

Lessons below:

When love and attentive care are available, kids don’t necessarily know they’re living in poverty.

When he was a baby, Sowell’s parents gave him to be raised by his elderly aunt (“more like my grandmother than my mother”) and her adult daughters, Birdie and Ruth. Sowell’s mother later observed that he had a better material life with his aunt than she could ever give him. Sowell’s father was ill, and they already had four children to care for. Raised by his aunt, Sowell describes how as a child, he was “loved, and perhaps even spoiled.”

As a young boy, Sowell, along with his aunt and her adult children, lived in a wooden house in North Carolina without electricity, central heating, or hot running water.

Despite this, Sowell writes, “It never occurred to me that we were living in poverty, and in fact these were some of the happiest times of my life…Once I tagged along with Ruth when she went to her job as a maid in the home of some white people. When I saw two faucets in their kitchen, I was baffled and said: ‘They sure must drink a lot of water around here.’”

Envy can backfire.

Thomas Sowell learned to read before he was four years old. He describes a story that stuck with him: There was a dog with a bone who saw his reflection in a stream and thought that the dog had a bigger bone than he did. He opened his mouth to try to get the other dog’s bone, and lost his own when he dropped it in the water.

People can be both proud and resentful of a loved one’s progress.

From North Carolina, young Thomas Sowell and his family relocated to Harlem. His older female cousins worked as maids and nannies in white people’s homes in New York and transmitted to Sowell things they learned, such as table manners and vocabulary. As he matured, Sowell also began reading and learning ideas and keeping up with current events. None of Sowell’s family had ever reached the seventh grade. Writing about his aunt, who he called “Mom,” Sowell says, “She became, and remained over the years, ambivalent about my progress—proud of my advancement yet resentful of being left behind.”

I sense some of this with my own adoptive family. My adoptive mom is clearly proud of what I’ve accomplished as the first person in the family to graduate from college. But when other members of our family talk about my success, she often changes the subject. This is one reason I almost never bring up anything happening in my life when around my family or old friends. And only speak about it if asked. I’ve written about similar themes here.

Some of this resentment between Sowell and his aunt boiled over. Later, in his teens, Sowell got himself emancipated and moved into a shelter for homeless youth.

People will lie if they think it’s for a good cause.

As a kid, Sowell was invited by his school to attend a two-week summer camp. When he went to speak with the people running the program, he was surprised to find that all the other kids there were white. He asked if any black kids were going to the camp, and they assured him that there would be. When Sowell arrived at the camp, he learned he was part of an experiment to put the first black kid into the program. Sowell concludes that it was “my first encounter with the notion that people who think they are doing something noble don’t have to tell the truth.”

Simple questions often have simple answers.

When Sowell was at the summer camp, he had the following exchange with one of the white kids:

“Tommy…?”

“Yeah.”

“…can you tell me something?”

“What?”

“How come…you don’t act like the colored people I see in the movies?”

That stumped me for a moment, and then I said:

“Well, they get paid to act that way—and I don’t.”

That seemed to satisfy him and, with a sigh of relief, he went back to where they had been.

When my two weeks at camp were up, he was one of those who came around to say goodbye. And he cried.

Objective measures of performance are ideal; relying on subjective evaluations is a major blunder.

Sowell describes how his middle school teachers’ “concern about our attitudes affected their judgments of our intellectual ability.” Sowell and some of his peers were troublemakers, which led the teachers to view them as academically unprepared. Yet Sowell and a large proportion of his classmates passed the entrance exam for Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech, and Stuyvesant (where Sowell went on to attend). This reminds me of a 2016 study which found that implementing a standardized testing requirement increased the number of poor and nonwhite kids in gifted programs. In other words, an IQ test administered to all students revealed that previously overlooked students from disadvantaged backgrounds qualified as academically gifted.

Similarly, another study found that when relying on their own impressions, teachers tended to view a kid from a low-income background as less academically competent, even when they had the same test score as a rich kid. The objectivity of scores can serve as a useful corrective to the subjective nature of teacher evaluations.

A passage from the book:

When Mrs. Sennett started with me and asked where I intended to apply to high school, I looked up briefly and said, “Stuyvesant High School” then went back to my sketching.

Mrs. Sennett threw up her hands in exasperation and said:

“Have you been listening to anything I said? What makes you think that you can go to Stuyvesant High School?”

“I have a friend who goes there,” I said, “and he never seemed to be a better student than I am.” I was of course thinking of Eddie Mapp.

“Oh really?” Mrs. Sennett said sarcastically. “Let me just look at your I.Q.” She began digging into the folders with great energy, as if eager to discredit me. When she got to my I.Q. records, her sneering expression turned to cold resentment. She went on to the next student.

In my view, schools should administer standardized tests (free and compulsory SAT or ACT) to all students in order to identify gifted youngsters from poor and marginalized backgrounds.

Life is tough all over.

Sowell worked a part-time job as a grocery delivery boy while he was studying at Stuyvesant High School in New York. The money he earned, though, barely covered his lunch money and subway fare to travel each day from Harlem.

Here’s Sowell at age sixteen:

I took my first full-time, year-round job as a Western Union messenger, delivering telegrams down in the grim and sometimes dangerous Chelsea district in lower Manhattan. It was my first encounter with low-income and sometimes semi-literate white people. Some of the older people from immigrant backgrounds could not read English, so I had to read the telegrams to them, and sometimes interpret them as well. It was my first realization that life is tough all over.

Scarcity breeds gratitude.

During an intense period of financial difficulty and family conflict, Sowell temporarily dropped out of school and moved out on his own before reaching legal adulthood.

From the book:

I learned how to look for a job—relentlessly. Each day, I would decide which was the most promising job to go for, and would arrive early enough to be first in line. When that interview was over, it was off to the next job on the list, and so on all day long, until I finally returned home, tired and dispirited, at the end of a long day of being turned down or told that they would get back to me. Then it was more of the same the next day, and the next, until I finally found something.

During one of these periods of unemployment, I fell behind on rent and began to skimp on food. It finally occurred to me that I could get some money by pawning my one suit. I took it down to the lower east side of Manhattan, where there were many pawnshops, and got some money for it. Immediately, I went to a little fast food place near the corner of Third Avenue and 14th Street, where I ordered a knish and an orange soda. It was delicious. No meal I have ever had since then, anywhere in the world, has ever topped it.”

Food tastes better when you’re hungry.

I never had any toys when I was living in the foster homes. When I was adopted, I got a few toys. I cherished each and every one of them, and never lost track of them. My sister had one stuffed bear that she carried around with her everywhere. Today I’ll often see kids with a room full of toys and stuffed animals and they have little to no interest in any of them.

Pay in the present to invest in your future.

As a teenager, Sowell, at one point, was working two different part-time jobs, one at a machine shop and one at Western Union. The Western Union manager told Sowell he had to quit his machine shop job because they needed him full-time. Western Union was paying him more, so the obvious choice was to leave the other job. But Sowell was friendly with the machine shop foreman and knew that if he remained there, he would gain more skills and, potentially, more pay. Sowell quit Western Union. This led to temporarily increased financial precarity, but Sowell was then hired at the machine shop full-time.

Don’t judge the discrepancy between the actual and the ideal; focus on what the reality-based alternatives could be.

Sowell describes how, as a young man, he took a keen interest in the unfolding of the Korean War. Upon learning that the Soviets had set up a puppet government in North Korea, and the U.S. had done the same in South Korea, he was outraged. He then acknowledges that this was because he hadn’t thought about what the realistic alternatives might have been, and concentrated only how the installation of these puppet governments was so far from the rhetoric of socialism and freedom.

Trust people who value being honest more than being nice.

As the Korean War intensified, Sowell was drafted into the Marine Corps. He notes that color did not matter, as all new recruits were treated with equal disdain. Sowell describes his life in the Marine barracks in Pensacola. There were two non-commissioned officers permanently stationed to oversee the young marines. One was Sergeant Gordon, “a genial, wisecracking guy who took a somewhat relaxed view of life.” The other was Sergeant Pachuki, “a disciplinarian who spoke in a cutting and ominous way” and was always “impeccably dressed.”

Sowell and his peers preferred Sergeant Gordon, as he was more easygoing. Sowell had to go into town to pick up a package. Sowell asked his Chief Petty Officer if he could leave the base to retrieve his package. Sowell received permission.

Later, while Sowell was not on base, he was marked as absent and was accused of being AWOL (absent without leave), a serious offense. Sowell knew Sergeant Gordon, the nice one, had overheard him asking for permission to leave the base. Gordon denied having heard anything, and told Sowell, “You’re just going to have to take your punishment like a man.” Gordon fretted that if he crossed the higher-ups, he would be reassigned to fight in Korea.

But unasked, Sergeant Pachuki came forward and spoke with the colonel, explaining the situation. As a result, Sowell was exonerated and returned back to his duties.

Referring to Gordon, the “nice” sergeant who betrayed him, Sowell writes, “People who are everybody’s friend usually means they are nobody’s friend.”

A “free good” is a costless good that is not scarce, and is available without limit.

Sowell would regularly needle Sergeant Grover, another member who outranked him.

Here’s the excerpt:

Some were surprised that I dared to give Sergeant Grover a hard time, on this and other occasions, especially since he was a nasty character to deal with. Unfortunately for him, I knew that he was going to give me as hard a time as he could, regardless of what I did. That meant it didn’t really cost me anything to give him as hard a time as I could. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I was already thinking like an economist. Giving Sergeant Grover a hard time was, in effect, a free good and at a zero price my demand for it was considerable.

Sowell learned he could receive something he enjoyed (pleasure at provoking Grover) in exchange for nothing.

Much of what you see has been carefully curated with an agenda in mind.

One of Sowell’s assignments in the Marine Corps was as a Duty Photographer on base. One day after submitting some of his photos, Sowell had the following exchange with the public information office sergeant:

“They are good pictures, he said. “But they do not convey the image that the public information office wants conveyed.”

“What’s wrong with them?” I asked.

“Well, take that picture of the reservists walking across the little wooden bridge carrying their duffle bags."

"Yeah. What’s wrong with it?”

“The men in that picture are perspiring. You can see the damp spots on their uniforms.”

“Well, if you carry a duffle bag on a 90-degree day, you are going to sweat.”

“Marines do not sweat in public information photographs.”

“Okay, what was wrong with the picture of the reservists picking up shell casings after they had finished firing? That was one of my favorites.”

“Marines do not perform menial chores like that, in our public relations image.”

“But all these photos showed a very true picture of the reservists’ summer here.”

“We’re not here to tell the truth, Sowell,” he said impatiently. “We are here to perpetuate the big lie. Now, the sooner you understand that, the better it will be for all of us.”

When I visited the Air Force recruiter in high school, I saw the brochures with images of well-groomed airmen in their dress blues graduating from basic training. I had no knowledge that much of that training would involve mind-numbing minutia. I suppose this is true for other career fields too. You see radiant coverage of academic research in legacy media outlets, or fun twitter threads outlining interesting research findings. You see the brand new hardcover book with all the glowing blurbs and reviews. You don’t see all the drudgery of research or writing behind the scenes.

Sometimes, it doesn’t pay to have too big a reputation.

Sowell and his fellow marines would sometimes have impromptu boxing matches around the barracks on base. One day Sowell was up against another guy and threw a sloppy right hand. The guy stumbled back, tripped, and fell to the ground. Although Sowell had swung and missed, witnesses thought he had knocked the other guy out.

Later, Sowell went up against another guy named Douglas. Douglas relentlessly came at Sowell and gave him a serious beating. Douglas told Sowell afterwards that the reason he was so aggressive was that he feared Sowell’s “one punch” could turn the fight around at any time. “Sometimes,” Sowell writes, “it doesn’t pay to have too big a reputation.”

Don’t say more than necessary.

Sowell was not above skating on thin ice, even as a marine. One Saturday, there was a Commanding General’s inspection. Sowell notes that at the previous inspection, no one bothered to take roll call, on the assumption that no one would dare be absent. Sowell decided to skip out and visit the library and go to a movie.

Later, he was summoned to his First Sergeant’s office:

“I don’t recall seeing you out there for the Commanding General’s inspection last Saturday,” he said.

I said nothing.

“Well,” he asked. “What do you have to say for yourself?”

“I have nothing to say for myself.”

“And why is that?”

“Because I am not responsible for the memories of First Sergeants.”

Since I was never one of his favorite people, I knew that if he had any hard evidence, he would have started proceedings for a court-martial, instead of trying to trap me into some damaging admission. When he realized I was not going for his bait, he dropped the questioning.

Let me tell you a story. Some years ago, a friend and I were both stationed at the same base. We were out bar hopping one night and he drove home. A cop pulled him over. After they exchanged a few words, the cop took him to the station to take a breathalyzer. By this point, it had been more than two hours since my friend’s last drink, and he passed the test.

The following day, he was called into our unit commander’s office.

“Just tell me the truth, man to man,” our commander said. “Were you drunk at the time the police officer pulled you over?”

“Man to man, sir?” My friend asked.

“Yes, of course. Look, it’s just the two of us here. It’s okay.”

“I was drunk.”

Our commander arranged for my friend to be court-martialed that week. He was subsequently discharged.

Never say more than necessary; especially when there’s no possible upside and a lot of possible downside.

Again, standardized tests are good.

Sowell was a high school dropout, having left Stuyvesent due to money issues. He then spent several years in the Marine Corps. After his enlistment, Sowell worked full-time and took a few night classes at Howard. He wanted to transfer elsewhere:

My over-all grade average was about a B minus. Nevertheless, my sights were aimed high: Harvard, Yale, Wisconsin, and Columbia.

The responses of these institutions to my inquiries were cautious rather than encouraging. Harvard warned me not to do anything rash, like quitting my job or withdrawing from the college where I was. They would consider my application, but that was all. Columbia rejected my application outright, a week before I took the College Board exams.

My test scores saved me. They were well above the national average and the college acceptances began coming in—though only Harvard offered any financial aid for the first year, in the form of a loan. They were candid enough to say that they were not convinced that they were doing my any favor by offering me admission and the small amount of aid that they did, for it would be very hard on me, both academically and financially. I liked their frankness and decided to go to Harvard.

Inhabitants of elite institutions treat smug assumptions as substitutes for evidence and logic.

By the time he was about to graduate, Sowell observed that he was “fed up with Harvard.”

From the book:

Perhaps any place with such an awesome reputation was bound to be something of a disappointment. What I most disliked about Harvard was that smug assumptions were too often treated as substitutes for evidence or logic. The idea seemed to be that if we bright and good fellows all believed something, it must be true. Unquestionably, Harvard made a major contribution to both my intellectual and social development. But when time came to leave, I felt that it was not a moment too soon.

Young people are in no position to judge “relevance.”

After graduating from Harvard, Thomas Sowell went on to attend the University of Chicago for his PhD in economics. He states that he had more respect for U Chicago than he ever did for Harvard. This is because U Chicago upheld strict standards of rigor, a marked contrast to the smugness of Harvard. Sowell describes taking a course with Milton Friedman, who would refuse to entry to his class to students who arrived late. Sowell notes that he was only one of two students to receive a B in Friedman’s course (“there were no As”).

From the book:

Some of the most important things I learned at the University of Chicago did not seem at all important at first. One of these things whose relevance I did not see immediately was an essay by Friedrich Hayek entitled “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” It was assigned in Milton Friedman’s course and it showed the role of a market economy in utilizing the fragmented knowledge scattered among vast numbers of people. It would be nearly twenty years later before I would realize the full implications of this plain and apparently simple essay—and then be inspired to write a book called Knowledge and Decisions. Students are often in no position to judge “relevance” until long after the fact.

Sometimes, you don’t realize how much tension has built up until after it has been released.

After receiving his PhD, Sowell got a job teaching at Douglass College. Sowell’s courses were difficult, and many average and mediocre students struggled. His department chair urged him to change his curriculum to make it easier.

Sowell refused and, eventually, resigned:

Although resigning was a tough decision to make—there was no other job offer on the table at the time—once that decision was made, I felt a great sense of relief.

Be careful about who you tell good news to.

After resigning from Douglass College, Sowell later received a job offer from American University. However, American University suddenly revoked the offer two days later, stating that they received “additional information” and advised Sowell to seek a post elsewhere.

Sowell reasoned that since he’d only ever had one academic job before at American University, that must have been the source of this additional information. He writes:

Articles of mine were accepted for publication in three scholarly journals during my year at Douglass College...In my naïve pleasure at getting the acceptances, I had shared good news with my colleagues—without realizing that some of them would never appear in even one journal of the same caliber in their whole careers. Whether prompted by envy or by resentment of my independence, the “additional information” supplied to American University was a knife in the back that could only represent vindictiveness, since my resignation had already relieved the department of any practical problem. It was another painful lesson in academic ethics.

Relatedly, Sowell also did a stint for AT&T before eventually returning to be a professor:

As someone returning to academia, I was welcomed back by my new colleagues as a prodigal son returning from the dog-eat-dog world of business. I had to tell them that the worst rumors I had heard at AT&T were not as bad as what I had personally experienced in the academic world. They thought I was joking.

The benefits of anonymity, impartiality, and colorblindness.

From the book:

Because the history of economic theory was of far more interest to scholarly journals in England and Canada than to those in the United States, most of my professional work was published outside the country. Though I did not realize it at the time, this was a long-term blessing, for the economists who ran these journals in other countries had no way of knowing what color I was, so I was spared the doubts that became increasingly common over the years among black academics, as to whether their achievements were really their own or were due to tokenism or double standards applied by whites.

Misguided sympathy and the importance of high standards.

Sowell later got a job teaching at Howard University, a historically black college.

He describes the rampant cheating he witnessed, and his attempts to crack down on cheating and low standards. Describing some of the students, Sowell writes:

I knew that whatever ‘front’ they might put up on campus, behind many of these kids was some father driving a cab at night, after working all day, or some mother down on her knees scrubbing some white woman’s floor, in order to send their children to college to try to make something out of them.

My tightening up on standards and on cheating initially meant massive failing grades on exams. This in turn meant massive complaints—to me, the department chairman, and to the dean. One girl who received a very low grade burst into tears and ran into a colleague’s office.

The book continues with a meeting with the dean, who essentially tells Sowell that his high standards are unreasonable, followed by Sowell’s response:

“We need higher standards, but we have to be reasonable. Kids from these backgrounds can’t handle a lot of abstractions, graphs, and things like that.”

“Yes, they can—but they will not do it as long as they have sympathetic administrators to intervene on their behalf.”

I wrote about this very topic here.

Good teachers don’t push ideological agendas.

From the book:

At the end of the term, a young couple taking my graduate seminar on Marxian theory came to me to express their appreciation for the course, but added:

“We still don’t know what your opinion is on Marxism.”

I took that as an unintended compliment—the best kind.

Sowell was a Marxist in his youth. When asked why he changed his mind, he replied, “Facts.”

At a UATX summer program earlier this year, one of the students told me, “Rob, when I scroll your Twitter, I can’t tell what you’re politics are.”

I just smiled and replied, “Good.”

Liberals thinking conservatives are mean dates back a long way.

Sowell, recently married, describes speaking with his friend:

“Marriage has made you almost human, Tom,” he said. “In another five years, when you see an old lady fall and break her leg, you’ll feel sorry for her.” Jim was a liberal and, to him, those who opposed liberals were just mean.”

Many academics are cowards, unwilling to defend the importance of a good education.

The book outlines Sowell’s experiences as a professor at Cornell:

The black students, or at least the more vocal of them, wanted education that was “relevant,” such as research in the ghetto.

Much of what the students said was sophomoric, but that is what to expect from sophomores. What had me aghast was that the white faculty members at the meeting were not only going along with it, but also were encouraging the students in a wholly paranoid vision of the “repressive” academic establishment, arbitrarily standing in the way of these wonderful ideas and projects.

I tried to argue that the most urgent educational needs of the students were for a solid foundation in academic skills…But the students clearly didn’t want to hear that. Neither did the white activist professors.

Sowell defended his position at a meeting with students and faculty. He continues:

I encountered a colleague from the economics department who had been at the meeting, and began arguing that the students’ proposals were self-defeating. He just listened as we walked across the parking lot. Finally, he said, “Of course,” got into his car and drove off. He knew better all along. It just wasn’t politic to say so.

Elite colleges aren’t necessarily “better” than others. But they generally expect students to quickly absorb and retain a lot of information.

From the book:

It was not that Cornell necessarily covered so much more difficult material than other institutions, though it no doubt did so to some extent. It was the speed with which we covered whatever we did cover…The amount of reading assigned, the amount of verbal facility and mathematical preparation presupposed, the quickness with which explanations were expected to be understood without elaboration—all these were geared to a student body which, in the liberal arts college, was within the top 5 percent in the nation.

During my first year at Yale, I went to office hours to speak with my developmental psychology professor about one of the assignments. He asked how I thought the class was going. I replied that the topics were fascinating, but the pace was relentless. He just smiled and replied, “Yes, we move along at a pretty good clip here.” The expectation (at least in normal courses not infused with identity politics) was that students should be able to absorb and integrate information quickly. Some professors took a twisted amount pride in the reading load they assigned to students.

Affirmative action has undesirable side effects:

One of the ironies that I experienced in my own career was that I received more automatic respect when I first began teaching in 1962, as an inexperienced young man with no Ph.D. and few publications, than later on in the 1970s, after accumulating a more substantial record. What happened in between was “affirmation action” hiring of minority faculty.

Debating dumb people is harder than debating smart people.

Thomas Sowell writes that before he was scheduled to debate Kenneth Arrow (Nobel prize-winning economist), someone asked him if he was nervous because Arrow was so smart. Sowell replied “I don't mind debating smart people. It's debating stupid people that's hard.”

The seventeenth-century Spanish philosopher Baltasar Gracián wrote, “Twice the wit is needed to deal with someone with none.”

Becoming a designated “expert” is often easier than you think.

From the book:

I was surprised to discover how fast and easy it is to become known as an “expert” on a number of subjects. The only subject on which I considered myself at expert was the history of economic theory, but others apparently considered me an expert on all sorts of other things.

Someone associated with writing The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups phoned me at the Center for Advanced Study because, as he put it, “You are considered the leading authority on West Indians in the United States.” Taken aback, I replied:

“Everything I know about West Indians in the United States could be said in ten typewritten pages, double-spaced.”

“But who else could write five typewritten pages?” he asked.

Apparently, there must be an expert for every subject, even if no one knows very much about it.

A few years ago, I’d written a couple of pieces about “cancel culture,” and suddenly people were asking to interview me about the phenomenon. I was unsure whether to do these interviews. I was just a PhD student studying psychology, and didn’t feel I necessarily had special insight into a relatively novel phenomenon. A friend of mine who is a professor said, “Look Rob, if you don’t do these interviews they’re just going to find someone else to speak with. And who knows what type of person that might be.” So I agreed to the interviews. The most surreal moment was on a video stream where the banner read something like “Rob Henderson: Cancel Culture Expert.”

The stuff of which successful politicians are made.

Sowell describes attending a fancy dinner with the then-California Senator S.I. Hayakawa. The economist Arthur Laffer was in attendance, and the senator told Laffer and Sowell that they should enter the next Republican primary.

Sowell gave this some serious thought, even speaking to a political insider, a “political pro” about it.

“Who’s going to be taking care of my son while I am running around every day trying to get votes?” I asked.

“Look,” the political pro said, “to a real politician, his family exists to help him get elected. If you see it differently, then you don’t belong in this business.”

Sowell then writes:

It took these pros very little time to decide that I was not the stuff of which successful politicians are made.

After Cornell, Sowell also worked at Amherst College and UCLA. Eventually, after seeing the decline in academic standards, battling administrators and students who wanted him to relax his grading policies, the infection of identity politics, and his overall disillusionment with academia, Sowell took a job at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, where he could devote his time entirely to research and writing.

On this, he notes:

“It would turn out to be the longest job I ever held and the most satisfying…Although teaching was initially what attracted me to an academic career, the atmosphere surrounding teaching now made it something to get away from.”

I can relate here due to experiences that led me to become disillusioned about academia. Seeing so many academics targeted, de-platformed, and/or fired for the most minor of offenses led me to give up on a traditional academic career.

Unique life experiences often make for a unique thinker.

Near the end of the book, Sowell concludes:

My early struggle to make a new life for myself under precarious economic conditions put me in daily contact with people who were neither well-educated nor particularly genteel, but who had practical wisdom far beyond what I had—and I knew it. It gave me a lasting respect for the common sense of ordinary people, a factor routinely ignored by the intellectuals among whom I would later make my career. This was a blind spot in much of their social analysis which I did not have to contend with.

With all that I went through, it now seems in retrospect almost as if someone had decided that there should be a man with all the outward indications of disadvantage, who nevertheless had the key inner advantages needed to advance.

Naturally, I couldn’t help but draw some comparisons to Sowell’s life and my own. The first half of his book was the best. For me, the struggle is always the most interesting part of memoirs and biographies. Sowell’s experiences living in poverty and homelessness in North Carolina and Harlem, dropping out of Stuyvesant, his trials in the Marine Corps, his struggle to make financial ends meet as a 24-year-old undergrad at Harvard, and so on. Astounding and propulsive. Once an author “makes it,” it’s nice to linger and enjoy their success with them. But for me, what drives any story are the setbacks and frustrations and how the person responds and overcomes them.

The script guru Robert McKee has written that “Nothing moves forward in a story except through conflict.” The crime fiction author Allan Guthrie, in his rules for writing, advised, “Torture your protagonist. It’s not enough for him to be stuck up a tree. You must throw rocks at him while he figures out how to get down.” The struggle is what is most captivating.

The book supplies insight into Thomas Sowell that you wouldn’t get from his articles, essays, and his other work. The British philosopher Isaiah Berlin once wrote:

“The deepest convictions of philosophers are seldom contained in their formal arguments: fundamental beliefs, comprehensive views of life, are like citadels which must be guarded against the enemy. Philosophers expend their intellectual power in arguments against actual and possible objections to their doctrines, and although the reasons they find, and the logic that they use, may be complex, ingenious, and formidable, they are defensive weapons; the inner fortress itself—the vision of life for the sake of which the war is being waged—will, as a rule, turn out to be relatively simple and unsophisticated.”

These convictions Berlin describes are often rooted in personal experiences. In an ideal world, the source of an opinion or an idea should not matter. In an ideal world, we would be able to evaluate beliefs and ideas on their own merits. In the real world, though, the source of an opinion often matters to people. Learning about a thinker’s “inner fortress” can lead us to take their ideas more or less seriously. With Thomas Sowell, it is clear that his personal experiences have shaped many of his broader views.

It is odd that A Personal Odyssey hasn’t been adapted into a movie or miniseries. One possibility is that Sowell is guarded and doesn’t want producers poking around into his life. This would make sense. I know people who know Sowell, and my understanding is he is quite reclusive nowadays, regularly turning down invitations to events and stating that anything he has to say, he can just write it. Another possibility is that Sowell is, as Steven Pinker described him, “taboo” due to his political leanings. Still, I don’t see why the Daily Wire or some enterprising right-of-center filmmaker would not take on this project. All this being said, books are usually better than films. But films can reach and inspire more people.

I have two minor criticisms of the book.

First, Sowell always comes out with the upper hand in any confrontational interchange. It’s possible that he is just that good. Still, as George Orwell has written, “Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful. A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.”

Similarly, the economist and memoirist Glenn Loury has stated, “How does the [memoirist] earn the readers’ trust when the writer is reporting on himself? The only way is by disclosing discrediting information. The writer’s got to put blood on it. You have to say things that are ugly about yourself for the reader to take you seriously.”

Sowell does portray his personal difficulties. But in his interactions with his teachers in school, his superiors in the military, his colleagues in academia, and his bosses, he is invariably the more clever one. It would have been interesting to get a glimpse into the occasions when he was one-down instead of always one-up.

Second, there is no discussion of Sowell’s family relationships as an adult. He gets married, he has a son, but these are mentioned in passing. Sowell is clearly a layered and complex individual, and getting a glance into his own experiences as a family man after having had such a tough childhood would have been interesting.

But these are minor quibbles.

Thomas Sowell is a living legend, and his memoir is now one of my favorites.

> A few years ago, I’d written a couple of pieces about “cancel culture,” and suddenly people were asking to interview me about the phenomenon.

One of my first blog posts to be widely circulated mentioned “lookism” and how masking during the pandemic had convinced me that looks-based biases were real. Those few paragraphs of text led someone to extend me a speaking invitation for a DEI panel. [which I declined]

Thankful for Thomas not giving in to silly social games. It is a serious bummer that educators don't understand or don't care that higher standards create better educated, and more capable students.