Better an Absence of Men Than Imperfect Men

Thoughts on communist takeovers + a review of “Meeting with Pol Pot”

In U.S. high schools, you get 155 hours of Hitler, 3 minutes on Stalin, and zero on Pol Pot.

Fifty years ago Pol Pot’s forces entered the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh. This was perhaps the most insanely murderous regime in human history. And this occurred to the cheers and satisfaction of Western leftist intellectuals.

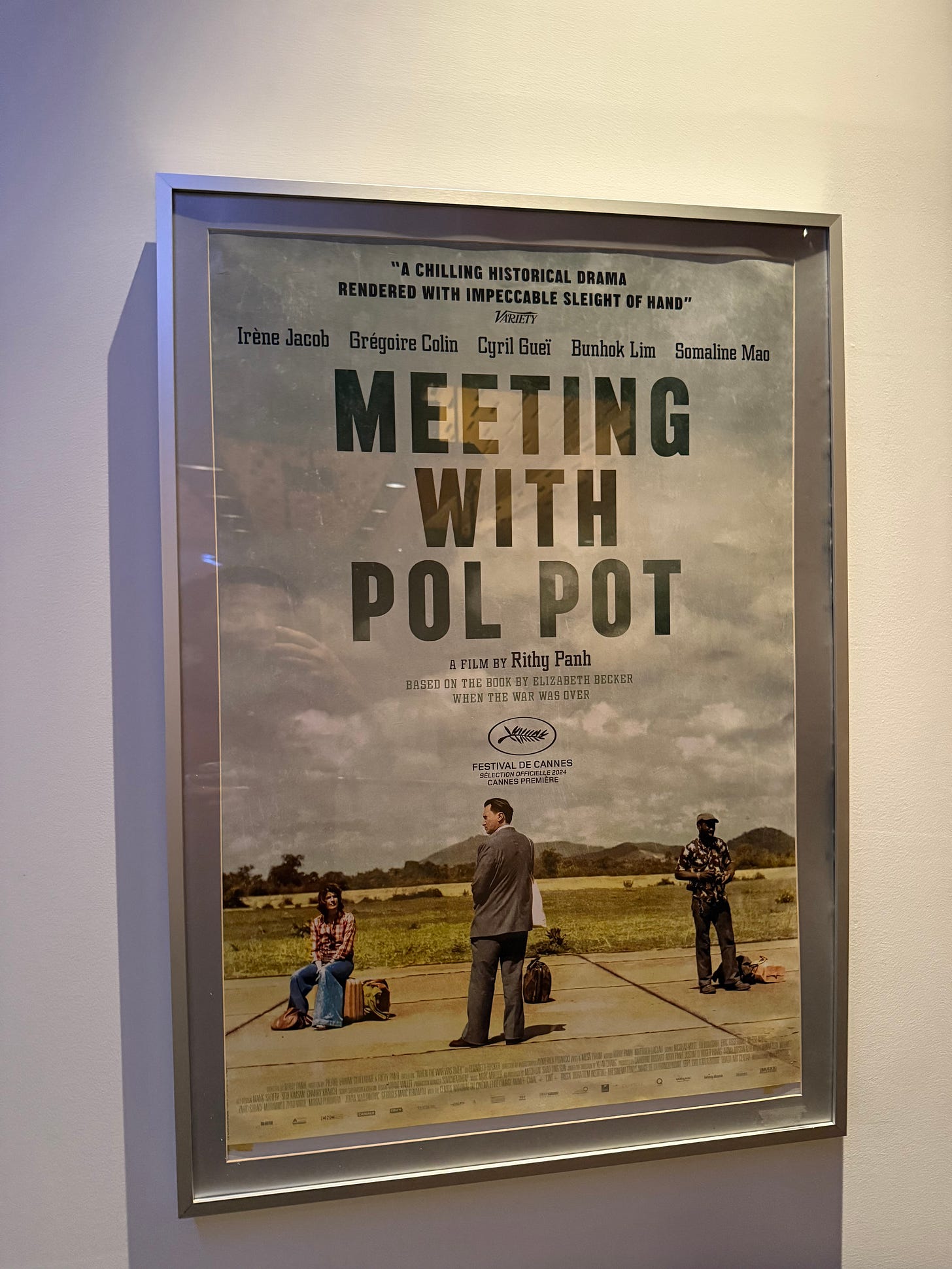

The Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh lost his entire family to the communist takeover and subsequent genocide in Cambodia in the 1970s. His new film, “Meeting With Pol Pot,” dramatizes a real 1978 visit to Cambodia by three Western journalists.

Many spoilers ahead.

At the time, the country was sealed off from the world. After taking power in 1975, the Khmer Rouge communist regime emptied the cities and forcibly relocated the population into labor camps. The film is loosely based on Elizabeth Becker’s 1986 book When the War Was Over.

One of the journalists in the film, Alain Cariou (played by Grégoire Colin), is a socialist academic who, as a young man, studied with Pol Pot in Paris. Both were student activists (shocking!).

Pol Pot grew up relatively well off and learned about Marxism and socialism as a student in France. Despite his family's relatively prosperous origins, in an interview in 1977, Pol Pot claimed that he was born into a "poor, peasant family".

You still see this among affluent socialists today, who cosplay poverty in an attempt to manipulate actual poor people into supporting their twisted ideology.

Later, after the communist takeover in Cambodia, Pol Pot and his boys would line suspected class enemies up against a wall and speak French to them. If they reacted (indicating they understood and were therefore rich/educated) he’d have them shot.

No one hates elites more than elites (or aspirational elites).

Once you understand this, then you understand why you’ll find 100 communists at an Ivy League or Oxbridge institution before locating even 1 at a community college.

Too many people mistakenly think that the battle is between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” What actually happens is the "haves" want to seize money from the "have-mores" and to do they so disguise their malicious desire as concern for the "have-nots."

Relatedly, many people misunderstand that clever intellectuals can be more dangerous than oafish jocks. Didier Maleuvre, a professor of literature at UC Santa Barbara, reminds us that, "large-scale harm is not committed by the frothing bully; it is done by well-mannered, affable, intellectual, and comparatively feminized coalition builders like, say, Lenin, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and other such well-spoken technocratic tyrants.”

Anyway. Back to the film. The journalist Cariou, now in his forties, arrives in Cambodia full of optimism. He looks forward to visiting his old friend Pol Pot. He wants to see the revolution up close. He believes the Western press has unfairly maligned it. Never mind the stories from refugees about forced labor, executions, starvation, and torture. Cariou is prepared to believe he’s witnessing the birth of a utopia.

Cariou parrots the regime’s slogans, praises their effort to create “a new man,” and seems genuinely impressed by the society he encounters: peasants stripped of names, possessions, education, and even eyeglasses.

Everything they see, every person they interview, every site they visit is orchestrated and manipulated to present a picture of harmony, equality and prosperity.

Reality gradually becomes harder to ignore. Cariou and his two fellow journalists become increasingly aware of how much coercion, torture, and outright murder is required to build this supposed “utopia.”

Still, Cariou clings to his beliefs. He wants the revolution to work. For Cambodia, of course, but for the ideals he once marched for as a student in Paris. The Khmer Rouge communists repeat slogans about human dignity. But there’s none of it in sight. Even in the Potemkin village the communist officials have orchestrated for the journalists, the sense of emptiness, desperation, and death in the air is unmistakable.

Gradually, you see Cariou move from confidence to unease to guilt. The film director Rithy highlights the painful process of waking up. Of watching a cherished worldview crumble under the weight of reality. Of famine, torture cells, and piles of human skulls.

Interestingly, Cariou is based on real-life British academic Malcolm Caldwell, who was executed under the orders of Pol Pot.

Cariou’s colleagues aren’t so easily manipulated.

Lise Delbo (Irène Jacob), a veteran journalist, covered Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

She approaches the trip with more skepticism and a personal question: what happened to her old interpreter, one of the many Cambodians sent off to labor camps and never heard from again?

The third visitor, Paul Thomas (Cyril Gueï), is a French African war photographer. He’s seen too much to be fooled. He objects when the communist officials try to stage every image and control every interaction the journalists have with the local population.

At one point in the film, Thomas quietly opens one of the neatly arranged sacks of rice—meant to show off the agricultural success of the communist regime—and discovers these sacks are actually filled with dirt.

Most of their visit takes place near the unfinished Kampong Chnnang Airport. The regime started building it in 1976 but never completed it. Thousands of forced laborers died there. Starved, beaten, executed. For years, the place was said to smell of death. Human bones would rise through the soil when the rains came.

There’s a reason Eisenhower instructed that the Nazi concentration camps be thoroughly photographed at the end of World War II. He told U.S. troops to document everything. Eisenhower understood that there would be people in the future who would deny it ever happened because they were naive about the depths of human depravity.

Today, we largely take for granted that murderous regimes can arise out of “hate” or other ugly motives. Many people have a difficult time, though, processing the fact that murderous regimes in the twentieth century also grew out of noble-sounding ideals like “equality,” “egalitarianism,” “human dignity,” and so on. Relatedly, you’ll often hear people accuse their opponents of “dog whistling” to subtly support fascism or far-right extremism. Communists don’t have to dog whistle, because their ideas are not stigmatized to nearly the same degree, despite the fact that communism is the frontrunner among murderous ideologies with regard to body count.

People focus on ingroup/outgroups, how people are cruel to outsiders, how people dehumanize their outgroup, and so on. More interesting to me is how communism got groups to murder their own people. Pol Pot, a Cambodian himself, got other Cambodians to slaughter millions of their fellow citizens. Same with Stalin and Mao. People who look just like you, speak the same language as you, eat the same food as you, practice the same religion, and so on. Still mass slaughter and unrivaled bloodthrist. Educators, psychologists, and formally educated people in general are weirdly uncurious about this.

Eventually, the journalists are granted a meeting with Pol Pot. When the moment arrives, the director Rithy doesn’t show him clearly. We hear a voice (actually Rithy’s voice) speaking from the shadows.

Pol Pot declares, “Better an absence of men than imperfect men.”

The effect is eerie. It reminded me of Colonel Kurtz from “Apocalypse Now” (my discussion/review with Trung Phan and Jim O'Shaughnessy here).

If you want to learn more about the history of what happened in Cambodia, I recommend reading Survival In the Killing Fields by Haing Ngor and The Lost Executioner by Nic Dunlop. You could also watch “First They Killed My Father,” a heartrending film directed by Angelina Jolie, based on the book by Loung Ung.

You’ll learn how Pol Pot directed a reign of terror that led to the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people, or about one-fourth of Cambodia’s population. Pol Pot was only in power from 1976-1979. In less than 4 years, 25% of Cambodia's population was killed. This is widely considered to be a genocide. Naturally, Western intellectuals at the time did all they could to deny what was happening.

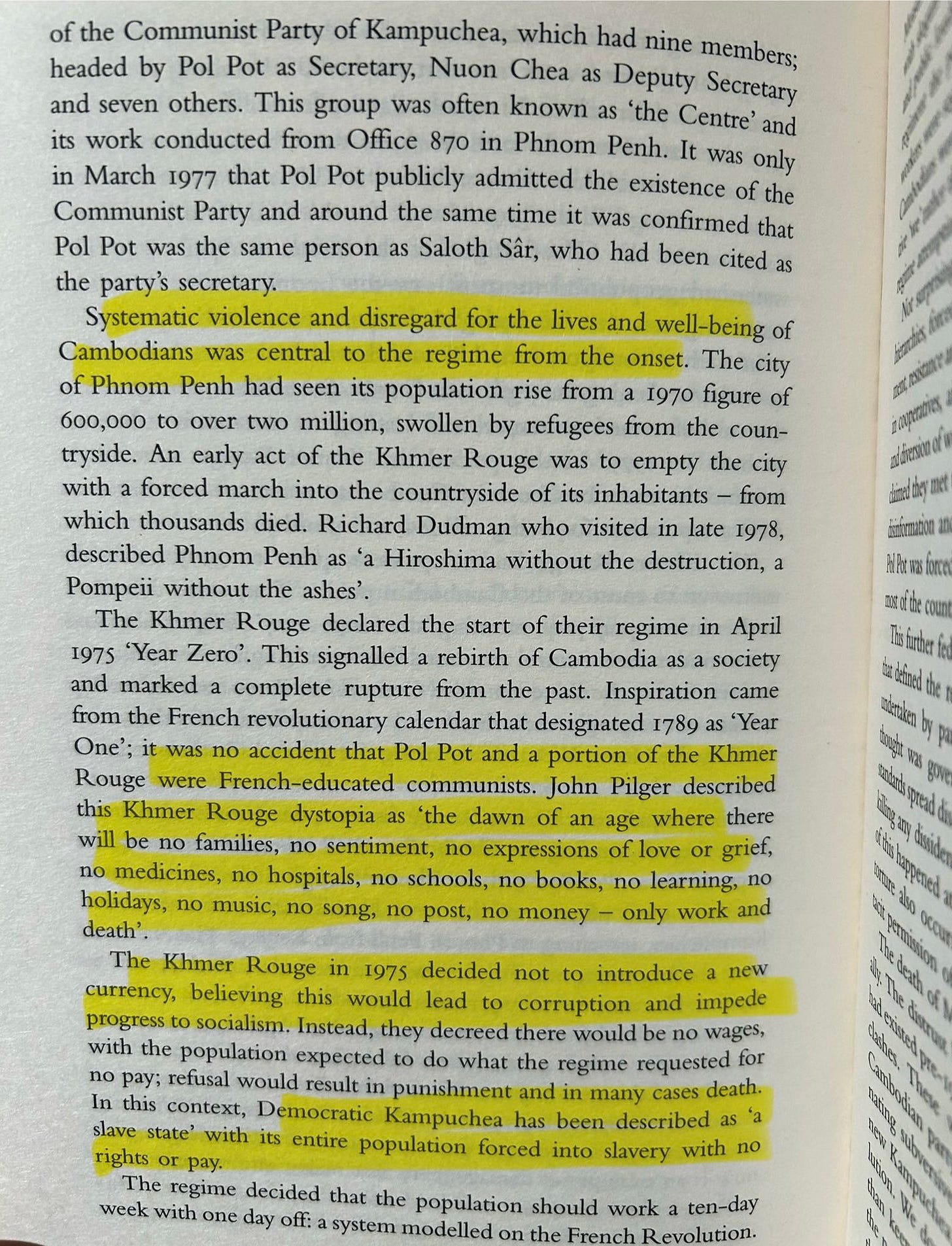

Pol Pot and his inner circle of communist revolutionaries tore apart Cambodia in an attempt to ''purify'' the country's society and turn people into revolutionary worker-peasants.

Many people were executed outright: former soldiers, civil servants, merchants, teachers, anyone labeled a “parasite” or “intellectual.” The elderly, the blind, the sick, and even children were tortured and killed.

As his project began to fail and famine swept the country, Pol Pot blamed those around him.

First it was loyalists from the pre-revolutionary regime. Then he blamed other Communist officials. Eventually, he targeted his closest allies.

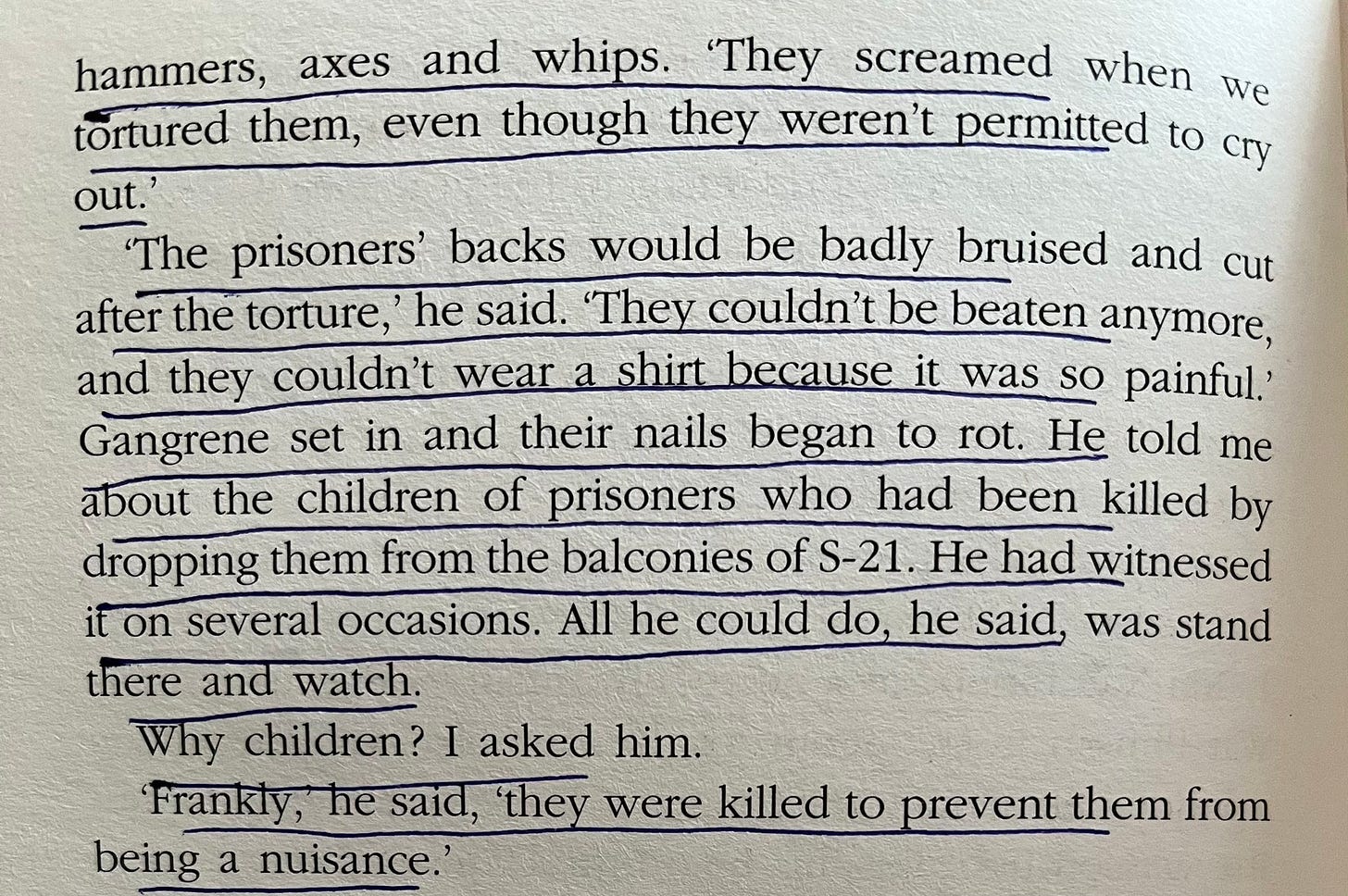

Suspected enemies were rounded up and sent to prisons, where they were tortured into confessing to imaginary plots. Then after confessing, they would be executed.

This part about communist regimes—the obsession with confessing one’s guilt—has always fascinated me. And it usually plays out the same way. The communists in Maoist China described it as “exhaustive bombardment.”

The interrogator will basically say, “Hey, we already know you are a spy/counter-revolutionary/enemy of the regime. We just need you to say so. And if you acknowledge your guilt, then this will all go so much easier for you.” Eventually, the tortured individual just wants the pain to stop and they acquiesce, believing that if they just confess to the imaginary crimes, they will be released or at least will no longer be tortured. So they confess. And once they have acknowledged their guilt, they are executed.

On this point, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn explained the logic of Soviet interrogation tactics: because guilt can never be absolutely certain, it is useless to seek evidence in the first place. Therefore, evidence is not necessary. Thus, the best proof of guilt is a confession. Which the interrogator must do his utmost to extract.

Communist officials in various regimes were obsessed with extracting confessions from the falsely accused. Why bother with confessions? One purpose is to shatter the idea of objective truth that exists independently of the Party. Another is to force the population to accept falsehood as a way of life. To humiliate ordinary people.

Why did the falsely accused confess? After all, people who are legitimately guilty often deny any wrongdoing. Of course, one reason is to get the torture to stop. And because the interrogator deceives the punished individual by saying “If you just confess, everything will be okay.” The historian Robert Conquest suggested that subjects of a communist regime are so conditioned to tell lies, that telling one more lie in the face of fabricated accusations is no big deal.

Years ago, I visited the Oranienburg concentration camp in Germany. There I learned that Nazi guards needed some kind of "reason" to murder prisoners. They couldn’t just indiscriminately execute people. “Official procedure” was required. This upheld the illusion that this was all somehow “legitimate.”

You can read this description of what happened in Somalia, and it looks no different from how communism worked in just about every other country in which it was implemented:

“I was born in Somalia in 1969. The country had achieved independence nine years before. But less than a month before I was born—on October 21, 1969—a junior member of the brand-new Somali armed forces seized power with the help of the Soviet Union. The first two decades of my life were shaped by the upheaval that followed that coup.

The Somalia that gained its independence was a young, optimistic society full of national pride. We had such hope for growth, political stability, prosperity, and peace. But, in a story sadly familiar to many of my fellow Africans, those hopes were dashed.

What followed was a nightmare.

For me it is all captured in the earliest memories of my youth: statues of Mohamed Siad Barre, our dictator, sprung up across Mogadishu, flanked by a trio of dark seraphim: Marx, Lenin, and Engels. This particular communist experiment plunged Somalia into bloodshed, mass starvation, and a 20-year period of suffocating tyranny. I recall my grandmother and mother smuggling food into our house. I also remember the whispering: we felt the state was omnipresent. It could hear everything.

My father was thrown into prison. His friends—those other pioneers in pursuit of a democracy modeled on America—were either jailed like him or, in many cases, executed.”

And yet there are still people who believe in this ideology. You can be a communist in a capitalist society. You can’t be a capitalist in a communist society.

In Cambodia during Pol Pot’s reign, temples were destroyed. Religion was abolished. Buddhist monks were murdered.

Under the banner of communism, the Khmer Rouge regime enslaved and murdered millions of people.

Families in Cambodia were torn apart. Husbands separated from wives, children from parents. Holidays and music were banned. Romance, prayer, joy—all outlawed. Local officials dictated who could marry. Disobedience meant execution. Children were forced to inform on their families.

Many of those who resisted, including children, were buried alive, dropped from balconies, or fed to crocodiles.

Work crews were formed to dig canals and farm land by hand, without machines. People labored from sunrise to late at night. The regime promised progress. Instead it delivered cruelty, hunger, and mass death.

Recall this quote from Thomas Sowell: “The history of the 20th century is full of examples of countries that set out to redistribute wealth and ended up redistributing poverty.” These regimes aimed to promote peace and instead promoted terror and violence.

It’s important to remember here that Pol Pot didn’t rise to power by promising to be evil. He promised goodness. He promised dignity. Fairness. Equality. A better world. He said he wanted to help the poor.

That’s always how it starts.

Neither Pol Pot nor the people who helped him were mustache-twirling villains. They were educated, articulate, and convinced they were on the right side of history. Evil usually doesn’t look like evil. This is the part that’s hard for some people to accept. Many of the worst atrocities of the 20th century weren’t driven by hatred or greed.

The communists in Cambodia turned an entire nation into a prison camp, then a graveyard. And they did this in the name of equality, fairness, dignity, and justice.

Good to read on the day that Marxist-Islamists are demonstrating in Times Square. Would that they could all be made to read it.

This reads like a cautionary tale of socialism, which is indeed true, but where is the cautionary tale about late stage capitalism? The entire reason people even consider socialism is because they are tired of late stage capitalism: private equity cannibalizing local businesses and communities to maximize profit, the wealthy bending the rules to benefit their industries (read: crypto), the financialization of real estate pushing housing out of reach for large swaths of people.

I am not saying socialism is the answer, but to me the (legitimate) criticism of socialism needs to be balanced with the (also legitimate) criticism of capitalism, which is arguably more relevant today as we actually live in a capitalist society, not a communist one.