Rage of the Falling Elite

How downward mobility fuels radical politics

In America, we love a rags-to-riches tale. Think of Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish immigrant who rose from bobbin boy to steel magnate; Oprah Winfrey, who grew up poor in rural Mississippi; even Elon Musk, the awkward South African transplant who transformed himself into the richest man alive.

These stories are endlessly recycled because they affirm a central American creed: that each generation can surpass the one before.

Today, however, that creed is starting to creak. In 2025, the most combustible force in American society isn’t upward mobility, but its opposite.

It’s easy to laugh at the caricature of the wealthy progressive—taking a knee in Brooklyn for Black Lives Matter, occupying a quad at Harvard for Palestine, or waving a placard outside the headquarters of a Fortune 500 company in the name of climate. Yet the radicalization of seemingly well-off people is one of the defining political developments of the past decade.

Consider how the upper middle classes lionized Luigi Mangione, who is accused of killing the CEO of UnitedHealthcare. Or how they propelled the socialist Zohran Mamdani toward becoming the next mayor of New York.

The children of affluence appear to be mobilizing—and boy, do they want you to know about it.

But what is really happening here? Why are people who appear to have “made it” rallying to causes at odds with their own standing?

The answer lies in a less romantic story than Carnegie’s or Oprah’s. It is the story of downward mobility.

For generations, Americans assumed that their children would live better than they did. Today, that assumption no longer holds. In fact, the higher your parents’ income, the less likely you are to match it.

According to The Pew Charitable Trusts, fewer than four in 10 children born into the richest fifth of households stay there; more than one in 10 fall all the way to the bottom fifth. Similarly, a 2014 study in The Quarterly Journal of Economics found that while 36.5 percent of children born to parents in the top income quintile remain there as adults, 10.9 percent fall to the bottom quintile.

Sociologist Musa al-Gharbi, in his 2024 book, We Have Never Been Woke, argues that this downward mobility of children born into wealth is the psychological engine of contemporary politics. This may look like a trivial problem—the petty disappointments of a small slice of America—but the unhappiness of this group, raised to expect the world and denied it, has outsize consequences.

To be clear, this cohort has never faced genuine poverty. Still, they have experienced the sting of loss: They came of age after the Great Recession, watched job security fade as the digital economy made their skills obsolete, and learned that highly coveted jobs in academia, media, and politics were far fewer than promised. These disappointments, al-Gharbi writes, helped power the Great Awokening. Many disillusioned strivers aimed their anger at the system they believed had failed them, and at the lucky few who did manage to retain or enhance their class position.

Unlike the working classes they so often claim to represent, these downwardly mobile elites remain armed with the tools of their upbringing: degrees, contacts, cultural fluency. They may no longer have the bank accounts their parents did, but they retain platforms in media, academia, and politics through which to broadcast their grievances. Given these advantages—or perhaps the right word is privileges—it should come as no surprise that their concerns, which seem to the average American profoundly niche, have dominated the cultural conversation.

Some of this downward mobility is voluntary. Al-Gharbi notes that many young, college-educated people would prefer “to be a freelance writer or a part-time contingent faculty member rather than work as a manager at a Cheesecake Factory.” The dream is artistic freedom and flexible work. The reality is disillusionment when prosperity does not follow.

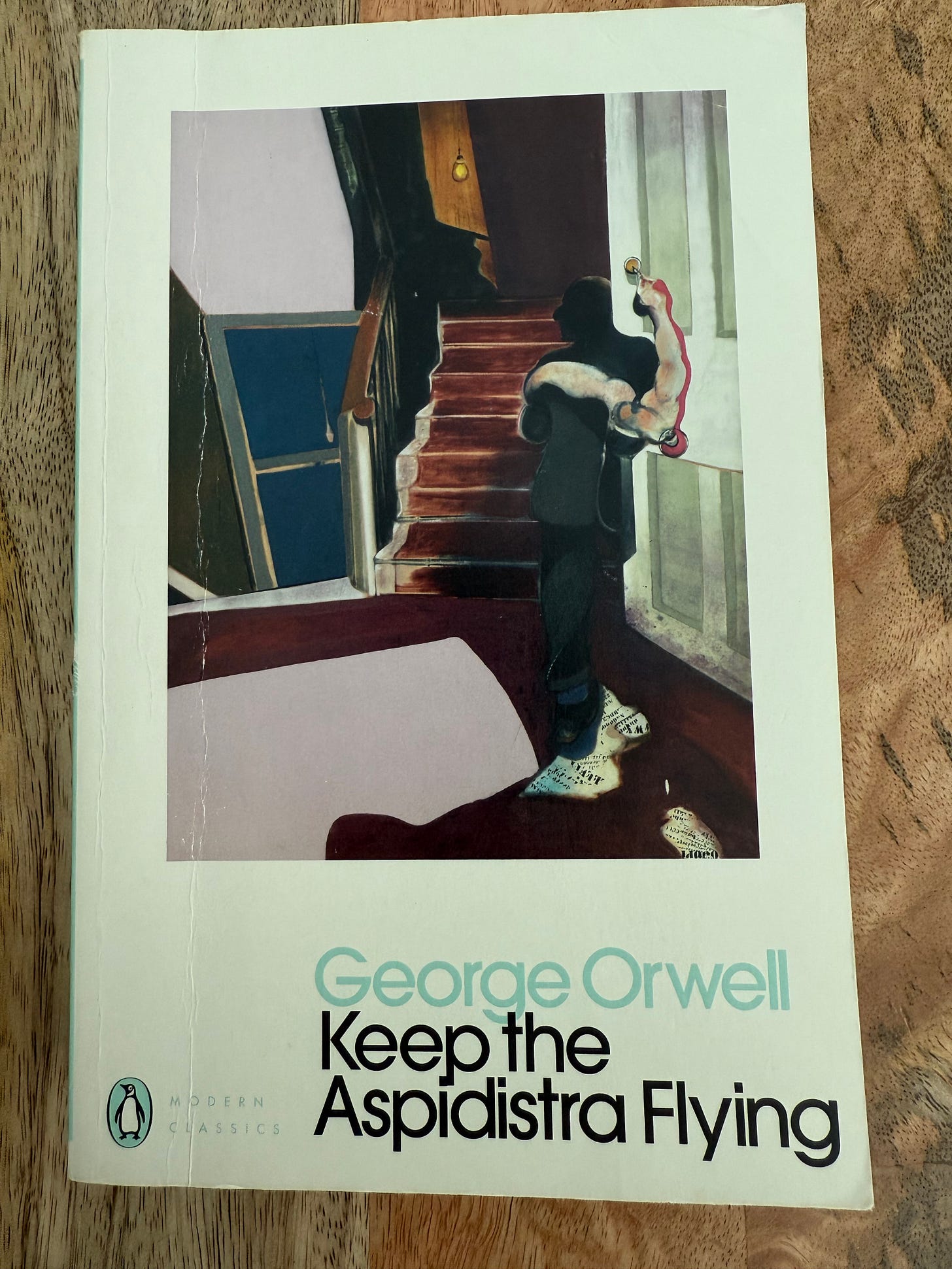

Such disappointment isn’t totally new. George Orwell’s Keep the Aspidistra Flying follows a Cambridge-educated poet who abandons his advertising career, squanders his inheritance, and slides into genteel poverty. HBO’s Girls replayed the same theme for a new generation: Brooklynites with cultural capital but precarious incomes, simultaneously privileged and resentful. The details change, but the shape of the story remains the same—raised in affluence, buoyed by expectation, they discover too late that their choices and the system cannot sustain them.

What is different today, however, is how the disillusion now manifests itself. When reality disappoints those raised in privilege, the gap between expectation and outcome produces rage. Behavioral economics has long recognized this dynamic: Satisfaction depends less on objective conditions than on whether outcomes match or exceed expectations. And today, those expectations are far from being met.

Two years before Girls ended, sociologist Lauren Rivera, in her book Pedigree, found that graduates of lesser-ranked colleges who landed jobs at elite firms were far happier than Harvard and Stanford graduates who landed the same jobs. The reason was simple: Those jobs exceeded the expectations of the former, while for the latter they fell short. The higher the expectation, the sharper the disappointment. The harsh reality, then, is that privilege itself can encourage feelings of decline. When you’re born to—and surrounded by—overachievers, even respectable achievements can feel second-rate.

In a 2018 study, Duke sociologist Jessi Streib explored why many middle-class kids falter in school and work. Her finding was counterintuitive: Entitlement often dragged them down.

It’s not too hard to see why. Success in school requires showing up, meeting deadlines, and tolerating authority. Success at work requires completing projects on time, absorbing criticism, and cooperating with colleagues. Yet the downwardly mobile, Streib found, were often convinced such requirements were beneath them. Their grandiosity and defiance hastened their slide.

As far back as 1987, a 40-year longitudinal study underscored this point. Even then, middle-class children who were emotionally volatile and prone to rage were more likely to experience downward mobility, and by midlife their occupational status was indistinguishable from their working-class peers.

This helps to explain why modern movements like Occupy Wall Street were filled not with the destitute but with college-educated professionals. These were not people starving; they were aggrieved that they were in the 90th percentile rather than the 99th. Surveys show progressive activists are wealthier, whiter, and more highly educated than the average American. They are nearly three times as likely to hold a postgraduate degree.

The dynamic has a name: elite overproduction. Coined by Peter Turchin, it describes what happens when there are more ambitious strivers than there are high-status positions. For Turchin, moderate competition can sharpen a society, but excessive competition destabilizes it. Those who lose out often become disaffected elites, many of whom share the values of the ruling class but resent being locked out of its highest tiers.

History shows it is these disaffected elites who often lead revolutions. Robespierre, Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Mussolini, Che Guevara, even America’s founders—all were well-educated and ambitious, close enough to the ruling class to see its flaws, but excluded enough to seethe with resentment. Their criticisms of the ruling class of their time were sharp because they had seen its flaws up close. As Financial Times columnist Janan Ganesh has put it, “The person likeliest to tear down a nation’s establishment is a half-member of it.” Widespread public discontent is not enough to trigger a large-scale conflict, civil war, or revolution on its own. For the masses to bring down a system, they need an individual or organization capable of solving the coordination problem of uniting large numbers of people toward a shared goal. Impoverished or “immiserated” masses remain largely inert unless they are organized and led by disaffected elites.

Many assume the central conflict in society is between the haves and the have-nots. In reality, much of the struggle is between the haves and the have-mores—people who are already doing well but want the money, resources, and status of those above them. They often disguise this ambition as concern for the have-nots.

Indeed, ambition compounds the problem. Research consistently shows that people of higher socioeconomic status are more likely to crave wealth, status, and prestige than those with less. Émile Durkheim recognized the dynamic more than a century ago: “The more one has, the more one wants,” he wrote. A 2020 Berkeley-Cornell study confirmed this: The affluent were the most likely to agree with statements like “I want a position of prestige.” Elsewhere, a University of Edinburgh study found that malicious envy—resentment at others’ success—was one of the strongest predictors of support for coercive redistribution.

The impulse, in other words, is not to lift up the poor but to tear down those who are one rung higher.

This pattern is not unique to our era. As the historian Michael Knox Beran has observed, in the early 20th century women from America’s wealthiest families were taught that their privilege was undeserved. Many responded with self-denial, repentance, and even sympathy for the Soviet Union. Eleanor Roosevelt—a New York aristocrat and future First Lady—spoke warmly of communism in 1939, calling Soviet innovations “a positive force in world affairs.” The Great Depression further radicalized a generation of Ivy League idealists, many of whom flirted with socialism and communism as they streamed into Washington. Part of the appeal was guilt, but part was also anxiety: They sensed their grip on cultural primacy weakening.

The postwar rise of the SAT accelerated this erosion, creating a more meritocratic system but also producing a more competitive and status-anxious elite. The WASP monopoly began to crack, and with it came a new, more insecure ruling class.

Today’s wealthy activists are the meritocratic descendants of this ruling class—and now, they face their own reckoning. Once upon a time, their education and résumés guaranteed them status. Now, as the economy stratifies, many feel themselves slipping. And once again, socialism—or its progressive equivalents—offers a way to explain the loss and to seek revenge on those who have outpaced them.

How this pent-up rage erupts is still unclear, but it’s certainly not going to be pretty. The children of privilege may not starve. But their disappointment—sharpened by ambition, magnified by envy, and amplified through elite networks—has the power to unsettle politics in ways that hardship alone rarely does.

The result, as we’re discovering, is a cruel paradox. While the American dream of upward mobility built this nation’s mythology, the reality of downward mobility may be what destabilizes it.

A version of this article was originally published in The Free Press under the title “The Revolt of the Rich Kids.”

I believe that a contributing factor to the “victim” self-identification (and accompanying rage) was in how so many upper middle class parents “hovered over” and worshiped their children, protecting them from any anxiety or disappointments (hard parts of reality) that they could and fostering an internalized sense of entitlement (participation trophies!). When the “trophies” for existing quit being awarded, victims of such injustice (wokies love the term “justice”) identified the oppressors as the “fat cats” who had grabbed up all the trophies.

Really excellent piece Rob. I am on staff at a small college and I see today's youth come in aimless and unfocused but they are on a prescribed path, and college is the next level up for them. What is interesting is that for all their knowledge of technology, social media they seem to lack a spirit to make things different. I came of age during the Vietnam war and its aftermath and I watched as those who couldn't adjust to society created their own worlds, people like the two Steves of Apple, of Nolan Bushnell, of Larry Ellison of Oracle, Gates and Allen and others. They came, saw a world they did not fit into well, and created a new one, that seems to be lacking in these younger generations. Instead they have been enculturated to believe that anger is the solution, we have lost something in the intergenerational transfer.