The Male-Warrior Hypothesis

“If conflict is like bad weather, women try to stay out of it, whereas men buy an umbrella.”

The male-warrior hypothesis has two components:

Within a same-sex human peer group, conflict between individuals is equally prevalent for both sexes, with overt physical conflict more common among males

Males are more likely to reduce conflict within their group if they find themselves competing against an outgroup

The idea is that, compared with all-female groups, all-male groups will (on average) display an equal or greater amount of aggression and hostility toward one another. But when they are up against another group in a competitive situation, cooperation increases within male groups and remains the same among female groups.

Rivalries with other human groups in the ancestral environment in competition for resources and reproductive partners shaped human psychology to make distinctions between us and them. Mathematical modeling of human evolution suggests that human cooperation is a consequence of competition.

Humans who did not make this distinction—those who were unwilling to support their group to prevail against other groups—did not survive. We are the descendants of good team players.

It used to be accepted as a given that males were more aggressive toward one another than females. This is because researchers often used measures of overt aggression. For instance, researchers would observe kids at a playground and record the number of physical altercations that occurred and compare how they differed by sex. Unsurprisingly, boys push each other around and get into fights more than girls.

But when researchers expanded their definition of aggression to include verbal aggression and indirect aggression (rumor spreading, gossiping, ostracism, and friendship termination) they found that girls score higher on indirect aggression and no sex differences in verbal aggression.

The most common reasons people give for their most recent act of aggression are threats to social status and reputational concerns.

Intergroup conflict has been a fixture throughout human history. Anthropological and archaeological accounts indicate conflict, competition, antagonism, and aggression both within and between groups. But violence is at its most intense between groups.

A cross-cultural study of 31 hunter-gatherer societies found that 64 percent engaged in warfare once every 2 years.

Men are the primary participants in such conflicts. Human males across societies are responsible for 90 percent of the murders and make up about 80 percent of the victims.

The evolution of coalitional aggression has produced different psychological mechanisms in men and women.

Just as with direct versus indirect aggression, though, homicide might be easier to observe and track with men. When a man beats another man to death, it is clear what has happened. Female murder might be less visible and less traceable.

Here’s an example.

There’s a superb book called Yanoama: The Story of Helena Valero. It’s a biography of a Spanish girl abducted by the Kohorochiwetari, an indigenous Amazonian tribe. She recounts the frequent conflicts between different communities in the Amazon. After decades of living in various indigenous Amazonian communities, Valero managed to leave and described her experiences to an Italian biologist, who published the book in 1965.1

In the book, Helena Valero describes arriving in a new tribe. Some other girls were suspicious of her. One girl gives Valero a folded packet of leaves containing a foul-smelling substance. She tells Valero that it’s a snack, but that if she doesn’t like it she can give it to someone else. Valero finds the smell repulsive and sets it aside. Later, a small child picks up the leaf packet, takes a bite, and falls deathly ill. The child tells everyone that he got the leaf packet from Valero. The entire community accuses Valero of trying to poison the child, and banishes her from the tribe, with some firing arrows at her as she runs deep into the forest.

The girl who gave Valero the poisonous leaf packet formed a win-win strategy in her quest to eliminate her rival:

Valero eats the leaf packet and dies

Or she gives it to someone else who dies and she is blamed for it, followed by being ostracized or killed by the community

This is some high-level indirect aggression. Few men would ever think that far ahead (supervillains in movies notwithstanding). For most men, upon seeing a newcomer they view as a potential rival, they would just physically challenge him. Or kill him in his sleep or something, and that would be that.

Point is, this girl would have been responsible for Valero’s demise had she died. But no one would have known. If a man in the tribe, enraged at the death of the small child, had killed Valero, then he would be recorded as her killer. Or if Valero had been mauled by a jaguar while fleeing, then her death wouldn’t have been considered a murder.

Interestingly, the book implies that Valero was viewed as relatively attractive by the men, which likely means the girl who attempted to poison her was also relatively attractive (because she viewed her as a rival). Studies demonstrate that among adolescent girls, greater attractiveness is associated with greater use of aggressive tactics (both direct and indirect) against their rivals.

The male-warrior hypothesis states that men developed the ability to cooperate and coordinate their behavior to jointly compete, and this arose from pressures in the ancestral environment in which male groups competed with other male groups to obtain resources and access to women. Research findings are consistent with this hypothesis. Intergroup conflicts are primarily driven by men. Men are the main victims of such conflicts. Men tend to be suspicious, aggressive, and unforgiving to outgroup males.

Women have these feelings toward unfamiliar men too, though less so. Their feelings tend to be expressed through fear and avoidance rather than overt conflict because of the risk of potential sexual coercion.

Interestingly these patterns are reflected in chimpanzees, too.

In his book Our Inner Ape, the primatologist Frans de Waal observes:

“Captive chimps are just as xenophobic as those in the wild. It’s almost impossible to introduce new females to an existing zoo group, and new males can be brought only after residential males have been removed. Otherwise, a bloodbath results.”

Aggression differs within versus between groups. Ingroup conflict is typically contained and ritualized while outgroup violence is all-out, gratuitous, and sometimes lethal.

As I’ve written elsewhere, a psychopath is a person who treats their ingroup the same way that normal people treat their outgroup.

On average, men appear to build stronger ties with ingroup members of the same sex than women. And tend to be more vicious toward outgroup members of the same sex than women.

Interestingly, men get along despite being more hierarchical than women, who tend to favor egalitarian relationships. One possible reason for this is that men often receive a romantic bonus from being friends with a higher-status individual whereas women often do not. Just by being a part of a male rock star’s entourage, a man will often find himself to be more appealing to women than he otherwise would be.

Corroborating this idea, a study found that young men desired friends who are intelligent, athletic, creative, socially connected, capable of financial success, and had a good sense of humor, much more than young women did.

Moreover, primatologist Frans de Waal has suggested that women are peacekeepers and men are peacemakers.

That is, within their groups, women are good at conflict prevention and have a general distaste for violence. And men are good at stirring up conflict against fellow group members and also good at subsequently resolving it.

Chimps also show this pattern. Female chimps have far fewer fights than males because they work hard to stay on good terms with those with whom they enjoy close ties. But if a fight does break out between females, they seldom reconcile. De Waal shares findings indicating that male chimps reconcile in about half of their confrontations, whereas females reconcile only 20 percent of the time.

His book Our Inner Ape goes on to describe how female chimpanzees feign reconciliation attempts in order to inflict more harm:

“The idea here is to trap the opponent using false pretenses. Puist, a heavy, older female pursues and almost catches a younger opponent…ten minutes later Puist makes a friendly gesture, stretching out an open hand. The young female hesitates at first, then approaches Puist with classic signs of mistrust, such as frequent stopping, looking around at others, and a nervous grin on her face. Puist persists, adding soft pants when the younger female comes closer. Soft pants have a particularly friendly meaning…Then, suddenly, Puist lunges and grabs the younger female, biting her fiercely before she manages to free herself. Reconciliations among male chimps may be edgy, sometimes even unsuccessful (meaning the fight starts all over again), but they never include trickery.”

This echoes Valero’s experience of another girl giving her a “gift” to get rid of her.

De Waal also describes a swimming coach who was interviewed about her switch from training women to training men. The coach observed that if two young women got into a fight at the beginning of a season, there would be little chance of reconciliation for the remainder of the year. Young men, on the other hand, were constantly belittling one another but at the end of the day they would still drink a beer together and a week later barely remember the conflict.

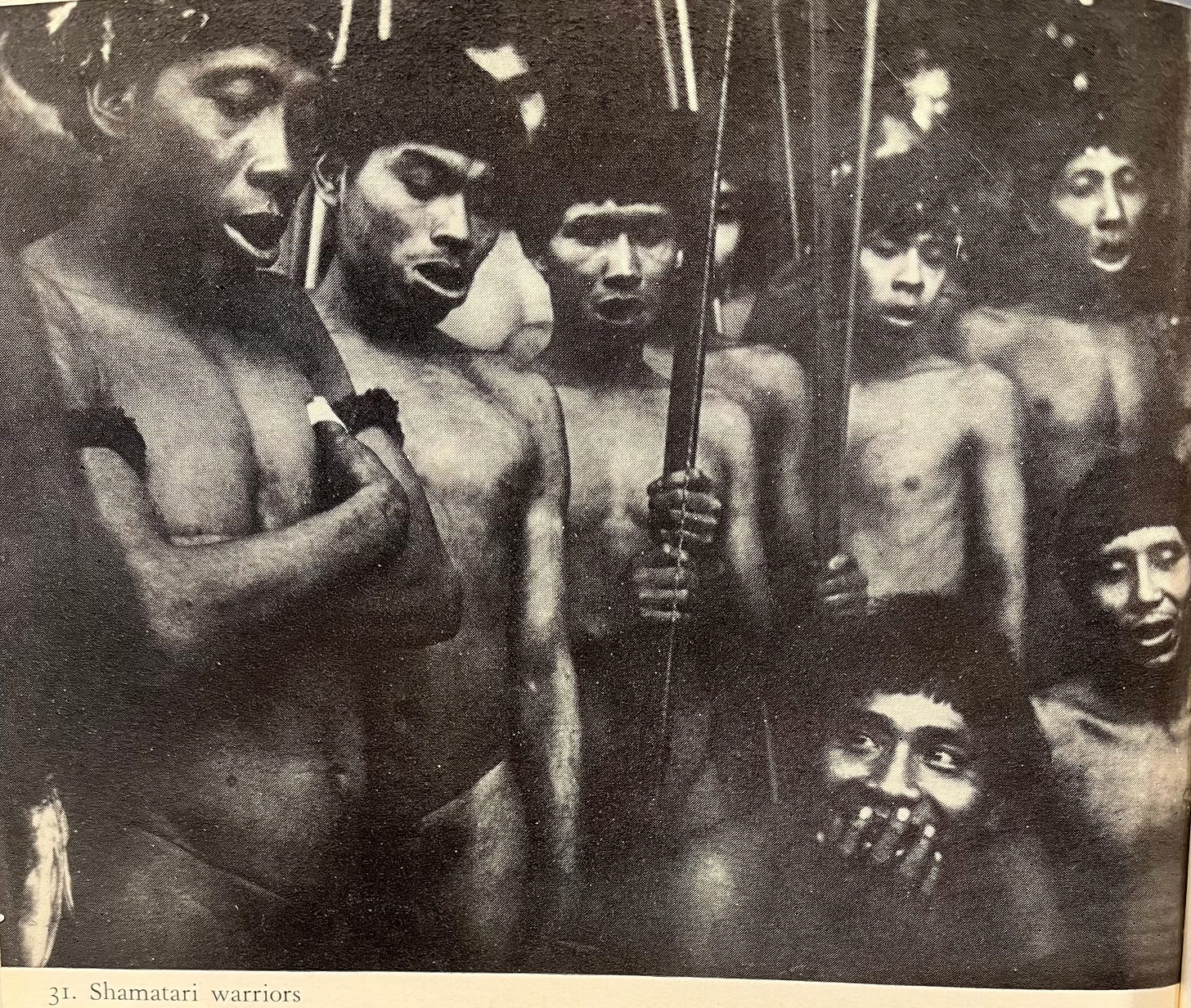

To be clear, some people interpret ingroup/outgroup as having to do with ethnicity or race or something along those lines. In fact, human group psychology evolved in an environment where every individual, whether ingroup or outgroup, was from the same ancestral group. In the ancestral environment, when nomadic hunter-gatherers primarily traveled by foot, no one would have ever met someone of a different race than themselves, whether in their own tribe or a rival one. In her biography, Helena Valero describes the Kohorochiwetari, Namoeteri, Shamatari, and other tribes who are constantly at war with one another, despite all having the same appearance and ancestral background (they paint their bodies, style their hair, and engage in scarification and piercings to distinguish themselves from one another). And, of course, there is the bloody history within European countries and within Asian countries—people who look similar killing each other. Our group psychology can be amplified or subdued by any coalitional markers. Today, most Americans would rather inflict suffering on someone of the opposing political party, rather than someone of a different ethnicity who was a member of the same political party.

Returning to the male-warrior hypothesis, human coalitional psychology seems to be more overtly pronounced among men. At least in ways that are easily visible and verifiable.

In addition to hunter-gatherer communities, the male-warrior hypothesis expresses itself in modern contexts. In a recent study of college and high school athletes, males were more likely than females to say that they had been the recipient of overt aggression (verbal or physical; name calling, fist fights, and so on) from one of their teammates.

In contrast, females were more likely to say they had been the recipients of indirect aggression (e.g., social exclusion; “wouldn’t pass me the ball during the game,” “teammates went to a restaurant without telling me,” and so on). Unsurprisingly, males were more likely to say that the aggression they received was physical, whereas females were more likely to report that the aggression they experienced was verbal.

A key finding from these studies is that compared to male athletes, female athletes were more likely to experience any form of aggression from their own teammates during a game.

In other words, when involved in a competition with another group, men—who are ordinarily at least as hostile as women when accounting for both overt and indirect aggression—suddenly become more cooperative. They redirect their aggressive energy toward the opposing team rather than toward one another.

As the researchers point out:

“This supports a key prediction of the male-warrior hypothesis, namely that males will do better than females in suppressing competition within their group when they are competing against an out-group…Apparently, men have a greater capacity than women to set aside rivalries and personal differences with groupmates when they find themselves competing against an out-group.”

There is an old Arab Bedouin proverb: “Me against my brother, my brother and I against my cousin, and my brother, my cousin and I against the stranger.”

The male-warrior hypothesis version would be something like “Me against my groupmates, and me and my groupmates against the outgroup.”

As long as individuals—especially men—feel a common purpose, they are good at suppressing their hostility to one another. But as soon as the common purpose is gone, tensions often rise to the surface.

Some of these tensions may in fact be unconscious methods of testing bonds. For a male, knowing where he stands with his group mates tells him how likely they are to prevail against other groups.

In Games Primates Play, University of Chicago professor Dario Maestripieri describes an amusing ritual among young monkeys. A monkey will walk up to a favorite social partner, stick a finger up his nose, and wait for a reaction. If their relationship is good, nothing happens. The purpose is to test the strength of their social bonds so that they can then form alliances against other monkeys.

Similarly, young human males often address each other with abusive insults. The ritual tests the strength of the friendship. If lighthearted verbal quips do not damage the relationship, then the bonds are likely relatively strong. In contrast, women and girls seldom insult their friends, and often work extra hard to praise them to avoid any signs of hostility. Men bond by insulting each other and not really meaning it; women bond by complimenting each other and not really meaning it. Relatedly, a 2018 study found that women prefer to take appearance-related advice from gay male friends (vs. female friends), because they believed female friends might sometimes give purposefully bad appearance-related advice as a means of mating competition.

Compared with women, men compete more overtly with one another to jockey for position within their groups but will suspend those tendencies when confronted with a group of outsiders. In contrast, women appear to compete more subtly with one another and are less inclined to suppress this tendency when competing against another group of women. Group competition in itself appears to be relatively novel among women relative to men. This is likely because men in the ancestral environment competed with their peers to appeal to women in their community. And they united with one another to fight against rival tribes. This typically involved defending their territory, resources, and women from outsider males, or capturing territory, resources, and women from other groups. The evolutionary psychology pioneer John Tooby has stated:

“The assertion that ‘culture’ explains human variation will be taken seriously when there are reports of women war parties raiding villages to capture men as husbands.”

This is stronger than I would put it (culture can explain plenty of human variation, just not as much as evolution). But it gets at the idea that among early humans, women didn’t form groups to seek out reproductive partners. In her biography, Valero details multiple situations whereby men fight over women or raid other groups and take their women. While she does share stories of women expressing jealousy or anger, there are no cases of them uniting together with the shared goal of overcoming another group. This doesn’t mean women are not capable of this. They clearly are.

But there is something peculiar about male psychology that makes them extra (overtly) antagonistic to their peers, and extra hostile to outsiders. This peculiarity and its encompassing features fall under the umbrella of the male-warrior hypothesis.

A quote from Frans de Waal, summarizing how males and females deal with same-sex skirmishes within their peer groups:

“If conflict is like bad weather, women try to stay out of it, whereas men buy an umbrella.”

The great evolutionary psychologist David Buss recommended the Yanoama book on Twitter. If David Buss recommends a book, then anyone interested in human nature should probably read it. I looked it up on Amazon (there should be a decent joke here). Because it is out of print, it was listed for around sixty-seven dollars. I went to a used bookstore a couple days later and randomly found it for five bucks. Lesson: visit used bookstores.

I wish someone would corroborate these findings in professional workplaces. I suspect much of it holds. In startups, being highly competitive would favor a mostly or all male team. But no one wants to say this. And I’ve seen the problems with mostly or all female startups again and again. Competition in the market doesn’t inspire female cohesion, so they have to work much harder to achieve it. They tend to prefer stable, peaceful workplaces, but these don’t naturally generate cohesion, they generate passive aggressive politics

“The lesson: visit used books stores.” ... Unless the store is outside your group territory. Then take an expeditionary force and visit used book stores “