Who Keeps the Castle Clean?

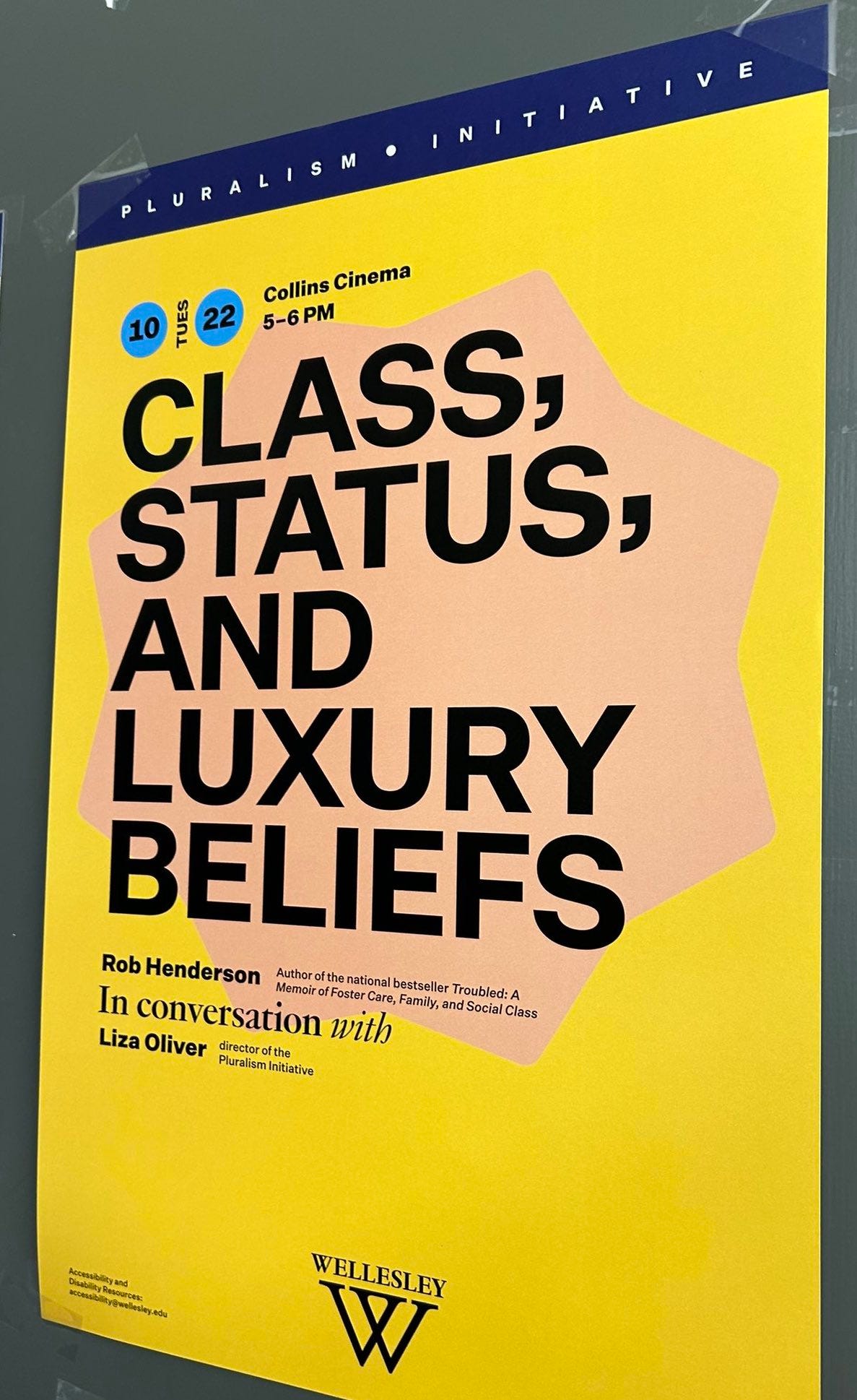

My discussion about social class at Wellesley College

Below is a transcript, lightly edited, with some highlights from my discussion at Wellesley College. We spoke about authenticity, elite hypocrisy, social mobility, and more. Enjoy:

Professor Liza Oliver:

So there's one anecdote that you gave in your book that when you arrived at Yale in 2015, there was a huge controversy that made national news regarding Halloween costumes and about the idea of cultural appropriation.

So the idea around cultural appropriation and offensive costumes, and you recount in your book you confiding in a friend that you didn't understand why everybody was so, so upset about this, why there was such an explosion on campus about it. And the person responded to you, "If you don't understand, you're just too privileged."

Can you talk about that a little bit?

Dr. Rob Henderson:

That was my first semester on campus, Yale in 2015. Let's see, I left the military in August and started class in September. And then in October I witnessed this wellspring of activism on campus attempting to get these two professors removed, one of them successfully, for what I thought was this fairly innocuous email. The university administration sent this email campus-wide essentially telling students to be mindful and to avoid cultural appropriation.

In response, hundreds of students marched around campus and called for her to be fired, and then for her husband to be fired for defending her. I was perplexed by this. I asked one female classmate what it was about the email that this professor had sent that was so offensive.

I knew that this classmate grew up in Greenwich and went to Exeter, an expensive private school. When she heard my question, she responded by saying I was too “privileged” to understand the pain these professors had caused. It took me a while to understand the intellectual acrobatics necessary to arrive there, which is essentially a form of stereotyping. She saw a cisgender, heterosexual, mixed-race Asian American male and made a series of assumptions about me.

In her mind, I must've had a very charmed life. Initially I was irritated by those assumptions, but gradually I just accepted it and found that because of those assumptions, I got a more accurate glimpse into what people really thought because they felt they could speak in a more unfiltered way around me. At least initially, before they spent a lot of time around me, they just assumed I’d grown up comfortably like they had, and therefore they felt free to fully express their views.

***

Professor Liza Oliver:

So on college campuses, there are specific kinds of oppression that we are very good at acknowledging and giving attention to, and there's other forms of oppression that we aren't and that we don't really recognize or talk about. And so I guess my question to you would be, why has the default of not understanding a particular claim that somebody makes—as in your case, "I don't understand"—why has the default become you must be too privileged as opposed to the opposite? Well, maybe it's because you haven't had access to the same kinds of conversations I've been having access to for a long time.

Dr. Rob Henderson:

A lot of graduates and students of elite universities will attempt to co-opt the suffering of marginalized people. They'll identify whatever commonalities they share with historically marginalized groups and then essentially co-opt the suffering of those people, even if they themselves haven't suffered.

They say, "Well, the category I belong to, there's been this long history of mistreatment." And then from there claim that anyone who doesn't understand what they've been through or what these marginalized communities have been through, they must be privileged.

But I mean, ironically, the less marginalized or the more privileged you are, the better positioned you are to accentuate your own marginalization because you can communicate it in a way that's palatable to upper-middle-class people.

Often what you'll find—and I struggled with this myself, and I speak to young people who have recently applied to college—if you've truly been through something stressful or traumatic, there's a reluctance to speak about it. You don't want that to be your identity. You want to rise above it by embracing a different aspect of your identity.

You want to talk about your interests or your intellectual preoccupations or the hobbies that allowed you to distract yourself from, or allowed you to draw your attention away from, those negative experiences. And if you ask them to talk about those experiences, they don't know how to put it into words that are sort of just the right amount of uncomfortable for the reader, the kind of Disney version of the story rather than the real thing.

Whereas people who have grown up relatively affluent and privileged, and maybe they've experienced some mild adversity, they know how to use the right language and the right jargon and terminology, hitting all those right buttons so that another privileged person can read it and say, “Okay, you're the right kind of marginalized, you're the right kind of person who knows how to communicate your suffering in a compelling way.”

***

Professor Liza Oliver:

So you are now part of the group, part of the class of people that you criticize.

Dr. Rob Henderson:

Is this my official membership induction?

[laughter]

Professor Liza Oliver:

Yes. You're welcome to the club.

Dr. Rob Henderson:

I'm a made man.

[laughter]

Professor Liza Oliver:

So what would you say to those who say you're a part of the group now and you're speaking from a place of privilege yourself now about lack of privilege?

Dr. Rob Henderson:

I talk about this in Troubled, this thorny conversation around class, that in America at least we want to believe that upward mobility exists. That if you check the right boxes and do the right things, you can ascend and join whatever group you want. But there's a great book called Class: A Guide Through the American Status System by Paul Fussell. And he writes about this American myth. But the truth, Fussell suggests, is that unless you're born into a certain social class, you can never really become a full member of it. And I point out some statistics in the book, some data indicating that if you have two people who have the exact same degree from the exact same institution, but one of them is a first-generation student and the other is a continuing-generation student, meaning they have at least one parent who went to college, the continuing-generation graduate goes on to earn something like $900,000 more across the course of their lives. Because there's more to class than just credentials; it's connections, it's mannerisms, habits of mind, who you know, how to conduct yourself and carry yourself in different social contexts. I had a friend at Yale who had also served in the military, and he didn't know how the deadlines worked for summer finance internships.

He wanted a job in finance, but he just didn't—he was not plugged into those circles, and he frantically had to submit his application at the last minute because he just was the first in his family to go to college. That knowledge wasn't readily available to him. So all of this is to say that, I guess maybe my résumé looks the same as the next upper-middle-class guy.

Maybe in some ways I could see that I'm an honorary member or something. But I am in this liminal space because I also don't necessarily feel fully at ease when I go back home or when I talk to my friends that I grew up around. That's one of the costs that’s under-discussed of upward social mobility. This is potentially one reason why people don't actually pursue opportunities given to them, because they don't want to leave their friends behind. They don't want to leave their communities behind. And that was, for me, an unforeseen cost of the path I ended up taking.

***

Professor Liza Oliver:

So I think critics of your position would say that you're clouding what are very real distinctions between oppressor and oppressed, and privileged and unprivileged, by making such claims about these categories seem disingenuous. Do you think that you are illuminating something new here that we're missing with these kinds of categories? The term 'luxury beliefs' is new.

Dr. Rob Henderson:

Wikipedia credits me as the originator of the term—if you believe Wikipedia, which some people don't anymore. But the idea—well, it's funny—as a writer or academic or scholar, you often think that you've come up with something original, and then you start reading through the literature and the research and the history of your field, and you learn that someone else discovered it a long time ago.

There’s a novel called The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James, which was published in 1881. And in that novel, there are characters talking about the radicals of the upper class and how their beliefs are “their biggest luxury.” And I'm reading this and I'm like, man, Henry James got there first [note: Adam Smith got there even earlier in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, published in 1759].

I make no claims to true originality—but I resurfaced this idea, gave it a name that people immediately connect with, and got people to think about how class is also a form of privilege. I spoke with this professor at Columbia Business School a few months ago, and he has preliminary data.

He and his PhD students recorded naturalistic conversations in the business school. They're coding these conversations that they're hearing around this elite business school, essentially attempting to identify how comfortable students are talking about their own marginalized identities. And he finds that students are very forthcoming when it comes to race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender.

Students will openly and freely—they're unafraid to talk about their experiences when it comes to those categories. But he says that the one area where students will not talk about, or where they seem very reluctant to talk about, is socio-economic status. Very wealthy students are apprehensive about talking about their family wealth. The low-income students are reluctant to talk about growing up poor. I would argue that lack of material resources is perhaps the most difficult—if you had to choose—growing up without enough shelter and food and warmth and so on. I mean, that might be the worst, but that is the one category that students don't want to talk about—is material privilege, class privilege.

Anecdotally, I've had conversations with academics and executives at top firms, and they talk about diversity quite a bit, but they don't talk about class diversity. And if you bring it up, often people will kind of acknowledge that that is an issue and maybe we should focus on it. But then they say, “Anyway, let's set that aside for now and concentrate on these other topics.”

***

Audience Member:

So you talked about upward social mobility and the cost of that.

I'm wondering if you can talk a little bit about how downward social mobility differs from that, and will people still carry their luxury beliefs when that happens?

Dr. Rob Henderson:

I've posted about this on social media and elsewhere. I would love to read a study or memoir or just something—some experience and something that captures that experience of downward mobility, because surely it must happen.

There've been a couple of surveys out of Pew, which find that if you're born into the top income quintile in the U.S., you have something like a 12% chance by the time you're 30 of ending up in the bottom. And so there is some churn and there's upward mobility, but there's downward mobility as well. And I think maybe those stories don't get discussed or described because they're more depressing, in some ways.

It's not as fun to read someone who starts with everything and then ends up with nothing. I'm overstating it, but you know what I mean. Would they carry their luxury beliefs with them? Probably yes. You could imagine all sorts of idiosyncratic paths and scenarios there, but people tend to, once people reach about age 25 or so, their sort of general outlook of the world remains pretty static.

***

Audience Member:

Just before I ask my question, I wanted to ask if you're familiar with Anthony Jack's idea of the "privileged poor" versus the "doubly disadvantaged"?

Dr. Rob Henderson:

I've heard of it and I'm vaguely familiar with it. Yeah.

Audience Member:

Well, I guess just to—the "privileged poor" is groups of students who would typically belong to their class—they're lower class—they belong to marginalized communities, but they have just been fortunate enough to go to—they're on scholarship at Phillips or something. But I was wondering, where do you think students who are part of that "privileged poor" group of people lie within all of this? Do they have luxury beliefs? Are they instilled upon them when they reach institutions such as Wellesley? When privileged poor students come to Wellesley, how are they impacted by people who have luxury beliefs that are actually part of higher class, or how does their perception of themselves change? All those questions.

Dr. Rob Henderson:

Yeah, I mean, this is purely anecdotal, but what I've noticed is two common paths. One, I guess, would be the path that I took where I became very repelled by what I was seeing and perplexed.

I've noticed others will almost go the opposite way where they realize, "Oh, if I want to make it in this institution, just tell me what I have to say and tell me what I have to believe and do, and I'll do it." And I've met people like that, and they're very good at it.

And I'm not even necessarily saying it's duplicitous or malicious in any way; it's just we're very good at convincing ourselves of the things we need to believe in order to rise in whatever organizational structure that we're in. For people who are first-generation students, people from low-income backgrounds, marginalized backgrounds—and also, I mean, in my case, I was also older and yeah, I had a bit of a chip on my shoulder for being older and for having the experiences that I'd had and thinking about how when I was 17, I was in basic training because I literally didn't have anywhere else to live at that time. And I see—I don't know, should I tell this anecdote here?

Professor Liza Oliver:

Yes, yes, definitely.

Dr. Rob Henderson:

Okay.

So I remember the day after the 2016 election, I showed up to class and no one's in the classroom, and five minutes passed. And one of the other students, she walks in and we're both just sitting there, just time is passing, and we're just, "Where's everyone?" And we open up our email and the professor writes, "It's a dark day in our democracy and we're all afraid and you can stay at home today." Class was cancelled.

I walk out and the campus is basically a ghost town, and apparently most of the classes that day had been canceled. And yet as I walked around Yale, I still saw the landscapers cutting the grass. I walked into the dining hall and still saw the staff serving food. I saw people cleaning gutters and washing the windows.

And what was going on in my mind—I basically saw the modern-day aristocracy staying at home crying, and I saw the staff keeping the castle clean for us. And I walked away just kind of disgusted by it. And so I also entered campus at a unique time, which is also maybe why I ended up with the views that I have and my interpretation of what I was seeing.

***

Audience Member:

Hi there. I'm interested in your modes, methods, or approaches to turning a mirror or holding up a mirror in upper-class spaces and how you sort of successfully scrutinize a group while maintaining a personal authenticity. And you touched on this idea of needing to sort of walk and talk in a certain way to be listened to.

So how do you hold an authenticity while also carrying yourself in a certain way to be heard and listened to in certain spaces?

Dr. Rob Henderson:

Authenticity—I think that there's what authenticity is and then what people think it is. I'll go out to a nice restaurant with some of my friends from college, and they'll say, "Oh, if the people knew the luxury beliefs guy was at this nice restaurant, what would they say?" And I reply, "I like good food."

That’s my authentic feeling about it. I also like fast food and In-N-Out and stuff too. I think all of the snobby attitudes that people have about junk food and fast food, I think some of it is a little silly.

When I recently visited one of my friends who I went to high school with. He's been in this holding pattern at community college for years now, and I'm seeing how his life is unfolding, and I guess it's more guilt than this feeling of not being authentic, but just realizing how much different my life has become.

The authenticity question—I just continue to do what I enjoy doing and not think too deeply about how it's going to come across to other people. I learned very early that I like money and that it's better than not having it. And so I'm unafraid to say it's nice to have money to buy things I like and enjoy.

Salute to the keepers of the castle.

Rob, how did you manage to keep your cool amidst the luxury belief scions? The stress of reading your article was just too much - I need a safe space for a good cry.