Why Cancel Culture is Fading

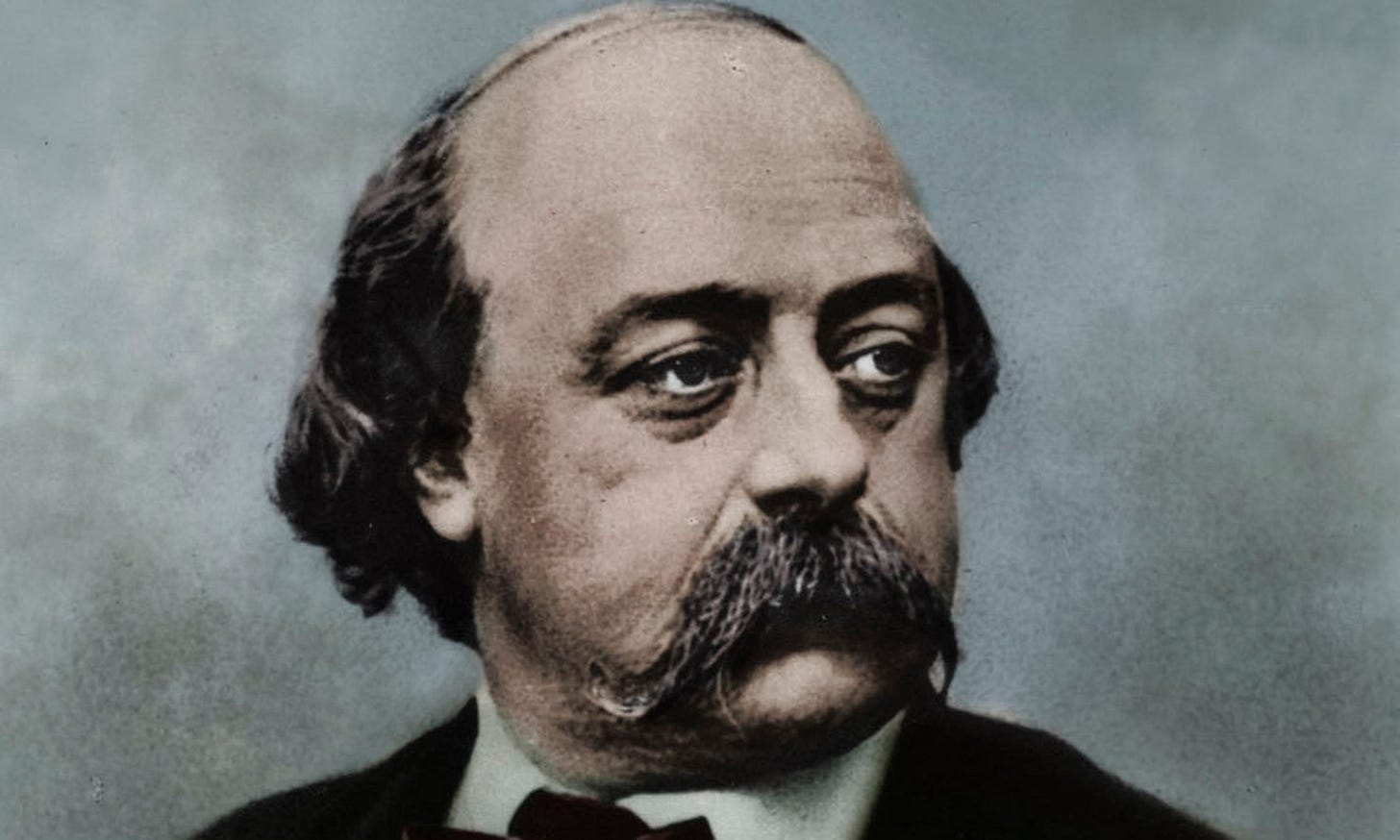

"Even when you take out the canines of a tiger, his heart remains that of a carnivore."

Cancel culture is fading. But this isn’t because people have suddenly become more tolerant. Rather, the hunting ground has changed and the prey have learned to hide.

Asked about being cancelled, Denzel Washington recently said, “Who cares? What made public support so important to begin with? You can’t lead and follow at the same time… You can’t be cancelled if you haven’t signed up. Don’t sign up.” His indifference is admirable. It is also uncommon. Reputation still matters, especially in elite worlds.

I saw this firsthand in 2019 at the University of Cambridge. At a social gathering with a group of doctoral students, I overheard them debating whether they could watch a Liam Neeson film. One American student insisted Neeson was “racist now,” referring to his confession of shame over some ugly thoughts he had held as a young man. Another student checked her phone, found that Neeson had been forgiven by large swaths of Twitter, and the group then headed to the cinema. It was both absurd and revealing. Educated people were outsourcing moral judgment to a social media feed.

At its peak, cancel culture functioned as a sophisticated enforcement system. The tactic was simple: make examples of high-profile figures to frighten everyone else into silence. Consider the sacking of the New York Times editorial page editor for running a piece backing National Guard deployments during the 2020 riots. Polling at the time showed that the majority of American voters supported the idea. Or consider Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the feminist novelist, who faced intense backlash in 2017 after stating that trans women had different life experiences from women born female, despite affirming equal rights for transgender people.

The lesson was blunt. Expressing a mainstream view could end a career if it violated elite narratives.

The mechanism was elegantly brutal. Activists identified a target, synchronised the message to create the appearance of consensus, and watched institutions fold under what looked like public demand. A small and connected minority passed itself off as the voice of the people.

The fear was clearest among the highly educated. A 2019 Cato/YouGov survey found that 25 per cent of those with a high school education worried about job risks over their politics. The figure rose to 34 per cent for university graduates and an astonishing 44 per cent for those with postgraduate degrees. The higher your education, the better you understood the rules of the game and the cost of breaking them. Consistent with these findings, the political scientists James L. Gibson and Joseph L. Sutherland revealed that self-censorship is more common in metropolitan areas than in rural areas (42% versus 33%, respectively). Cities are where highly educated elites cluster, and they are more intolerant of differing viewpoints than most other people.

The tactics of cancel culture were both solemn and flippant, which made them especially effective. Targets were accused of grave moral offences. Anyone who questioned the severity of the punishment was told to relax because it was “just people being mean on the internet.” Moral authority and plausible deniability, used in rotation, protected the process from scrutiny.

As Robert Greene has written in his book The Laws of Human Nature, “We live in a very politically correct time...the nicest, most liberal, most progressive people on the planet...behind closed doors, they turn into raging manipulators who will do anything to get exactly what they want. Power is timeless.”

The public pile-ons were only the surface. The real work happened behind closed doors. Academics quietly blackballed colleagues. Hiring committees excluded candidates for their views. Journals retracted papers for their conclusions rather than their methods.

The strategy relied on punishing the powerful to terrify the rest. In 2020, hundreds of scholars urged the Linguistic Society of America to strip Harvard professor Steven Pinker of honours. But Pinker understood the real target—it was a warning shot aimed at every graduate student, junior academic, and untenured professor watching from the sidelines, telling them to keep their mouths shut.

As Pinker memorably put it, the atmosphere resembled The Sopranos: "Nice career you've got there. It would be a real shame if something happened to it." Often the problem wasn't that people were being cancelled for expressing outrageous views, but that they were cancelled for expressing views that might very well be correct.

You do not have to topple every public intellectual. You only need a few scalps so the rest fall in line. The goal was never to punish everyone. The goal was to frighten enough people to create the illusion of consensus.

So why the decline in cancel culture? The easy targets are gone, and the survivors have learned to keep quiet. The campaign worked too well. People with heterodox views were either purged or trained to self-censor so thoroughly that there is no one left to cancel.

Another reason is structural. When Elon Musk bought Twitter (now X) in 2022, he did not just acquire a website. He disrupted the central coordination hub for the activists, academics, and journalists who ran cancellation drives. The people who once set the daily script lost their primary tool.

Users previously banned — including Alex Jones and Donald Trump — were reinstated, reflecting Musk’s “free-speech absolutist” stance. Musk also reinstated the Babylon Bee, a Christian satire outlet that had been banned for naming the former US assistant secretary for health, Dr Rachel Levine, who identifies as transgender, as 2022’s “Man of the Year”.

Some decamped to Bluesky and similar sites to little effect. As sports journalist Ethan Strauss put it, without Twitter they are “like a genie locked in a lamp. Yell, shriek, beat your chest, it doesn’t really matter. It’s just noise that echoes within a sealed chamber.”

X’s user base is not large relative to other social media platforms, but it is unusually influential in media, technology, and finance. For that cohort, nothing matches its density of information or its interest-driven network effects. Whoever controls that machine helps decide what counts as the day’s conversation.

You can see the desperation. Earlier this year, Democratic senators tried to flood X with the identical reply “That shit ain’t true” to counter opponents. The stunt revealed how much control they had lost. Without the ability to simulate consensus, their posts blended into the noise.

But cancel culture has not entirely vanished. In recent years, the energy once concentrated on the left has been growing on the right. With more influence in Congress, a sympathetic Supreme Court and growing control of state governments, conservatives now have the power to advance their own version of cancellation.

Some of this has taken the form of laws and executive orders targeting flag-burning or requiring immigrants’ social media to be scrutinised for “anti-Americanism”. In April, the US Naval Academy cancelled the author Ryan Holiday’s lecture an hour before it was due to begin. He had refused to delete slides highlighting the removal of more than 500 titles from the academy’s library — books that had been purged under DEI-related orders.

And this week, Cracker Barrel, the southern comfort food chain, scrapped a rebrand after a wave of conservative backlash. The company had unveiled a new logo in an effort to modernise, but reversed course days after Trump himself blasted the rebrand on Truth Social as critics accused the firm of abandoning “nostalgic Americana”.

These may not look like the online pile-ons of the previous decade, but the logic is similar. You do not need to silence everyone. You only need to target enough examples so everyone else falls into line. The danger is not whether cancellation comes from the left or the right, from institutions or from social media. The danger is that any faction with power will be tempted to use it to punish opponents and enforce conformity.

The motives underlying cancel culture remain: envy, a desire for power, the thrill of the chase. Much of what is now acceptable today will be heresy tomorrow. Posts that seem harmless now may be exhumed years from now and used against you. The mob is quiet, not absent. It is waiting for the next inevitable cultural shift and fresh prey. Sooner or later, the hunt will resume.

In any society, there exists a small percentage of highly aggressive people who will always adapt to political, cultural, media, and technological innovations. As Gustave Flaubert once wrote, “Speak of progress as much as you want. Even when you take out the canines of a tiger, and he can only eat gruel, his heart remains that of a carnivore.”

A version of this article was originally published by The Times under the title “A new kind of cancel culture is brewing — on the right.”

I live in Austin. I can report that conversations are still circumscribed among the college educated according to feminist social justice orthodoxy, and people in social settings are still highly unlikely to push back against the assertion of leftist ideological dogmas. So, cancel culture has faded on the internet, but the signs of its success are found in small group settings and institutions.

Rob, you do not distinguish between the Left's cancellations which are in service of tearing down established practices and customs, and those of the Right, which try to protect them. It is custom which constitutes the culture and provides social cohesion, and while here and there in need of careful improvement, should not be indiscriminately torn apart in pursuit of a grandiose imagined Progressive future. That is nihilism, which has unfortunately become ubiquitous.