Despite What They Say, Elite Colleges Don't Promote Equity

Playing musical chairs at elite universities disguises the real problem

The main result of a new paper led by Raj Chetty confirms the obvious: The most prestigious colleges in the U.S. are far more likely to admit applicants from rich families rather than applicants poor and middle-class ones, even when they have equivalent academic qualifications.

But there were also several other intriguing and less predictable findings from the study.

The paper, titled “Diversifying Society’s Leaders? The Determinants and Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Private Colleges” has received a lot of news coverage.

To me, this was perhaps the most intriguing headline about the paper:

Which the Atlantic later changed to:

The 12 colleges in this new study encompass the 8 Ivy League colleges: Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Brown, Dartmouth, the University of Pennsylvania, and Cornell. The other 4 are Stanford, MIT, Duke, and the University of Chicago.

Outside of the upper and upper middle class, there is a commonly held belief that “Ivy League” is synonymous with “elite/fancy/expensive/famous college.” I believed this myself. When I was learning how to apply for colleges in 2014, I recall being surprised that Stanford and MIT were not Ivy League colleges.

The meaning of the term actually refers to a collegiate athletic conference (hence “league”), but it is now associated with prestige, academic excellence, and social elitism (and not necessarily in that order).

The researchers of the study use the common term “Ivy-plus” to describe the 8 colleges along with the other 4 highly selective schools.

Many students and graduates of such colleges take pleasure in speaking about the prestige and power of these schools. And debating (sometimes playfully, sometimes not) where their particular institution ranks along the status hierarchy.

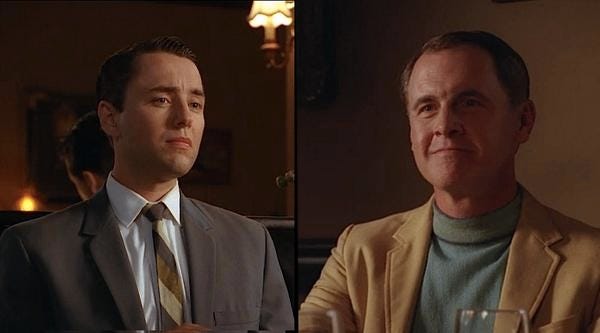

In Mad Men, there’s an amusing scene where Duck Phillips tells Pete Campbell about a meeting he’s arranging with a client:

Pete (scoffs): Fine. Who is he?

Duck: Mike Sherman. Princeton ‘52. You should have a lot in common.

Pete: I’m Dartmouth ’56!

Duck: Don’t pretend like you’re not gonna jack each other off.

The chattering class spends a lot of time speaking about how much effort, stress, and fretfulness surrounds applicants who aspire to enter such colleges. Tellingly, there is less discussion about how these exhausting games do not cease for students who are admitted. Arguably, the status anxiety becomes even more intense if admitted.

In a study from 2014, researchers asked students from Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania (an Ivy League college, but less famous than Harvard) to write down 7 things they would say when describing their university to other people.

Compared with students at Harvard, students at the University of Pennsylvania were significantly more likely to use the word “Ivy” to describe their school. They wanted to emphasize their membership in this rarified group.

For social categories, people who belong to a highly regarded group near the group’s boundary are more likely to highlight their membership in the group. For those who are comfortably in the group, and not near its boundary, they usually have little desire to signal their membership. Their position is secure.

You can see this with racial “passing.” In the U.S. and elsewhere, light-skinned ethnic minorities would attempt to “pass” as white to access the privileges that accompanied that social category. Nowadays, you often see a version of the opposite—white people pretending to be Black or Hispanic or indigenous to advance their educational or professional ambitions. This also occurs today with mixed-race people with a white parent. They feel less secure in their nonwhite status, so they double down on activism or broadcasting certain opinions to ensure people accurately consider their position to be on the “correct” side of the group boundary.

In my case, because I am half AAPI and half Latinx, I will inconsistently invoke whichever racial identity cajoles white people (the round-eyed devil) into giving me the largest amount of unearned benefits.

These elite colleges are the factories where the ruling class sausage is made.

In the press, the main finding of the new Chetty paper has been simplified into this NPR headline: “Affirmative action for rich kids.” It’s not wrong.

The finding that, controlling for grades and test scores, applicants from rich families are more likely to be admitted is not entirely surprising. In addition to academic excellence, the true mission of these institutions (whether they will admit it or not) is attracting and cultivating elites.

One reason elite universities have lasted so long is that historically they have been good at forming ties with every elite faction so that no matter who wins in an intra-elite conflict, the victors channel resources to support their survival.

Paraphrasing a scene from The Social Network, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton are older than the country they’re in. These 3 institutions were founded before 1776. They have survived multiple social upheavals because they are good at identifying and admitting elites, aspirational elites, counter elites, aspirational counter elites, and so on.

This phenomenon gives rise to some interesting dynamics on elite campuses. Today, you can find establishment types with ties to various government agencies and anti-establishment types whose one true wish is to subvert the U.S. government. In a way, these elite colleges hedge their bets by hiring both types on the faculty and admitting both types into the student body. No matter who wins, these schools come out ahead.

As I mentioned, there were some unexpected findings from the new study as well.

In a classic study from 2002, the authors (Dale and Krueger) found that after controlling for academic ability, graduates of highly-ranked universities do not, on average, wind up earning more than those who attend lower-ranked ones. They examined differences between students admitted to the same colleges but attended different ones. For example, imagine two students get into Princeton. One actually goes to Princeton and graduates. The other admires his Princeton admission letter but ultimately decides to remain close to home and attends Sacramento State. Who will go on to have higher earnings? The results of the 2002 paper suggest you might as well flip a coin. The researchers found no impact of going to an elite college. There was, on average, no added bonus, suggesting the ability to get in is more predictive of future earnings than actually attending.

The new Chetty paper found basically the same result. They looked at students who were waitlisted at Ivy-plus colleges. And they compared applicants who were admitted from the waitlist with those who were not.

This clever design allowed the researchers to determine whether attending a top college actually has any benefit for long-term success.

Overall, the researchers found that attending a top college had zero or close to zero impact on average earnings. Similar to the result of the 2002 Dale and Krueger paper, this new finding suggests that ability is more important (for earnings) than actually attending an elite school.

However, Chetty and his co-authors found that compared with waitlist rejects, waitlist admits to elite colleges are:

60% more likely to have earnings in the top 1%

Twice as likely to attend a top 10 graduate school

3 times more likely to work for a prestigious organization (e.g., Goldman, McKinsey, Google, the NYT/WSJ, etc.)

Relatedly, a study a couple of years ago found that roughly half of NYT and WSJ editors and writers are graduates of elite colleges.

So in terms of average expected earnings, going to a top school doesn’t seem to matter all that much. But that “average” masks a striking difference at the upper tail of the distribution.

Attending an elite institution essentially buys you what one of the paper’s authors (David Deming) describes as a “lottery ticket.” It increases your odds of entering the economic or cultural elite.

For earnings, it probably doesn’t matter what college you go to. But if you want to change society, influence others, help to determine what the educated public is speaking about or what they consider to be important, then where you attend might have some impact.

In my case, I probably had the ability to build an audience through my writing regardless of educational pedigree. But my strong hunch is that it would have been harder to get my op-eds placed in outlets like the NYT and WSJ. It would have been more difficult to get a good book deal from a major publisher. People who shape culture and policy might have been less likely to take my writing seriously.

Of course, people who don’t attend selective colleges still obtain book deals and place op-eds in major outlets. Returning to the lottery analogy from David Deming:

“Since you attended an Ivy-Plus college, you get 2 tickets. Friends who attended a selective public university get one ticket, and those who didn’t go to college get none. Your odds are double anyone else’s, but you still probably won’t win.”

If you don’t go to college, your odds of joining the economic or cultural elite are so low they might as well be zero. If you go to a good public college, you’re in the game; you have a minuscule but real shot. If you go to an elite institution, you go from minuscule to small.

In other words, most graduates of elite colleges don’t enter the 1% or go on to attain vast amounts of attention and influence.

So attending an elite college has little effect, on average, on future earnings.

But among those who do attend such schools, what predicts future outcomes?

The researchers found that, all else equal, applicants with high non-academic ratings (e.g., legacy, athlete, extracurriculars, and other “holistic” admission factors) don’t do any better in terms of future earnings or graduate school attendance.

However, academic ratings strongly predicted later life success.

More surprisingly, while students with high academic performance were more likely to later be employed at a prestigious firm, athletes were less likely. This is at odds with the idea that top firms that pay well want competitive, good-looking, well-adjusted people who aren’t “grinds.” Maybe things have changed and that stereotype is outdated.

There was also this:

If you control for test scores, admissions committees assign similar academic ratings for rich, middle-class, and poor applicants.

This isn’t exactly surprising (after all, they controlled for test scores).

But the fact that rich students received far higher marks on “nonacademic measures” like recommendation letters, extracurricular activities, and other components of “holistic” admissions criteria is telling.

More insight into why they hate standardized testing so much.

As I’ve said before:

Elite colleges eliminated the SAT before they eliminated legacy admissions. Tells you all you need to know.

Could there be more social class diversity at these schools? Yes.

One of the paper’s authors estimated that there are roughly 25,000 students per year from low and middle-class families that meet the academic standards necessary to be admitted to an Ivy-plus institution. 25,000 is a lot of students.

Still, I think the whole idea of playing musical chairs with seats at elite universities is a distraction.

A lot of people ridicule trickle-down economics. To simplify, the idea is that if you let rich people keep all their money, somehow that money’s going to magically trickle down to the hands of the dispossessed and the poor.

The whole discussion around affirmative action, whether based on race or class is similar.

It’s trickle-down meritocracy.

The idea is that if more people from marginalized and historically mistreated groups attend elite colleges and obtain positions of influence and power, this is somehow going to benefit the groups to which they belong. If we just pluck a few of those people out of their communities, the reasoning goes, and admit them into elite colleges, then somehow the benefits they receive are going to trickle down to the communities that continue to languish. This doesn’t happen.

It's not the job of elite universities to help the poor and disadvantaged and oppressed. Obviously. But they should stop pretending that’s what they do. It’s duplicitous and cringeworthy. Yes, they will admit students from impoverished and historically mistreated groups, provided they meet certain academic standards. These colleges want to identify those students. They’re not interested, though, in helping to improve the deteriorating communities from which the students came. Elite universities are not in the business of improving the lives of the poor/marginalized/dispossessed. They’re in the business of attracting and shaping elites. That’s fine. But be honest about it.

Matthew Yglesias:

“Top universities want to affirm values like 'diversity, equity, and inclusion,' but the whole point of top universities is to be elitist, hierarchical, and exclusionary...If you want to cultivate excellence among a social elite, then own up to that.”

The chattering class expends more frantic energy trying to ensure that the precise demographics of the ruling class match the country overall rather than trying to improve the lives of those who are truly marginalized or dispossessed.

A trivial 0.8 percent of all college students attend an Ivy-plus institution. The notion that these elite schools promote anything like “equity” is an idea that exists solely in the stunted imaginations of the luxury belief class.

On a recent podcast, NYU professor Scott Galloway pointed out:

“Elite colleges have effectively become the domain of two types of people: the children of the rich, and the freakishly remarkable. Our society shouldn’t be the Hunger Games. We should be looking at the unremarkable kids too, and figure out how to give them a shot.”

Galloway is speaking specifically about economic opportunities. Nothing wrong with that. I’d focus at least as much, though, on a shot at improving children’s early lives. Well-meaning people like Prof G have been trained to speak in the language of economics and education. We could also concentrate on promoting stable families, attentive parents, and good social and emotional health for kids. Somehow we’ve decided, as a society, that it’s okay if a child grows up in hell as long as he somehow manages to go to college and achieves upward social mobility. I haven’t signed off on that, even if the luxury belief class has.

Most students at Ivy-plus colleges come from upper or upper-middle-class families.

Suppose we expel all of them. Suppose we replace them with the 25,000 academically-equipped poor and middle-class students in the analysis I referenced above. These 25,000 talented youngsters receive elite pedigrees. They obtain high-paying jobs. They gain more pathways to power and influence. How nice for them.

What about the rest of the young people in the languishing communities, impoverished families, and dysfunctional neighborhoods they were plucked from?

Out of sight, out of mind, I guess.

I just finished The Fourth Turning Is Here. As someone in my eighties who has lived through the three previous eras described as Turnings by Howe I can say that they are a big deal. The fit is truly going to hit the shan in the next few years, and the result will probably be a levelling like the one following WWII. I operate a tree nursery in rural Texas south of Houston and the immiseration of the lower working class has gotten much much worse in just the last two years. People who could always find something are now broke, out of work, and hungry, and other parts of the country are probably a lot worse. Ideas like the Basic Income pushed by Andrew Yang are going to get a lot of attention as this immiseration spreads. As a descendent of flyover country gentry, town doctor, large farmer, I have lived to see the strip mining of capable people out of those areas. The level of federal debt is obviously unsustainable, the Woke manifestation has no solution for it or anything I can see. Academia and government have become a new Planter Class. The Planter Class lived off the stolen labor of their slaves. Academia is living on the stolen future labor of their students via student loans and government is living on the stolen labor of everyone by incredible borrowing.

“Elite colleges have effectively become the domain of two types of people: the children of the rich, and the freakishly remarkable. Our society shouldn’t be the Hunger Games. We should be looking at the unremarkable kids too, and figure out how to give them a shot.”

Kudos to this article whose subject is rarely discussed in polite or "meaningful" circles since those who would be spearheading the discussion are members of the unclothed emperor's cabal. Anyone else would be deemed unqualified or simply envious. Rob Henderson is among a vanishingly rare sliver of writers with a foot in both camps so to speak, whose experience and perspective is harder to dismiss. Those of us who graduated from state universities (Indiana University here) and at a time (1974) when simply earning a legitimate degree was a huge differentiator, it has been shocking to see the ever increasing hegemony and snarkiness and buffoonery from those with Ivy-plus pedigrees that they try to lord over the rest of us who they wish would simply bow down to their magistic superiority. They really can't understand our lack of reflexive worship. I strongly suspect that many in my cohort would love to see the rapid implosion of the charade which is the "Prestige of the Ivys." If that implosion were to happen in a manner akin to the how long it took the ill-fated Titan recreational submarine to snuff out the lives of its (mostly) smug occupants - who among the readers of this blog would shed a tear?