Killing A Bad Strategy Before It Kills you

How to use limited means to achieve aspirational ends

Alexander the Great supposedly kept a copy of The Iliad on his nightstand and a dagger under his pillow.

His ambition—to become Achilles—was just out of reach.

The means to do it—a dagger—was directly within grasp.

On Grand Strategy by historian John Lewis Gaddis covers roughly 2,500 years of history, pulling from writers, statesmen, theologians, and political philosophers. Rather than presenting a single thesis, the book is more of a synthesis—something Gaddis pieced together over decades of teaching. The book is dense at times, simply because of the sheer range of ideas it engages with. But it stands as one of the most concise and nuanced explorations of grand strategy. I first encountered these ideas as a student in John’s class at Yale.

The book draws on sources as varied as historian Thucidydes, political philosopher Machiavelli, strategist Carl von Clausewitz, psychologist Daniel Kahneman, novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, and many, many others.

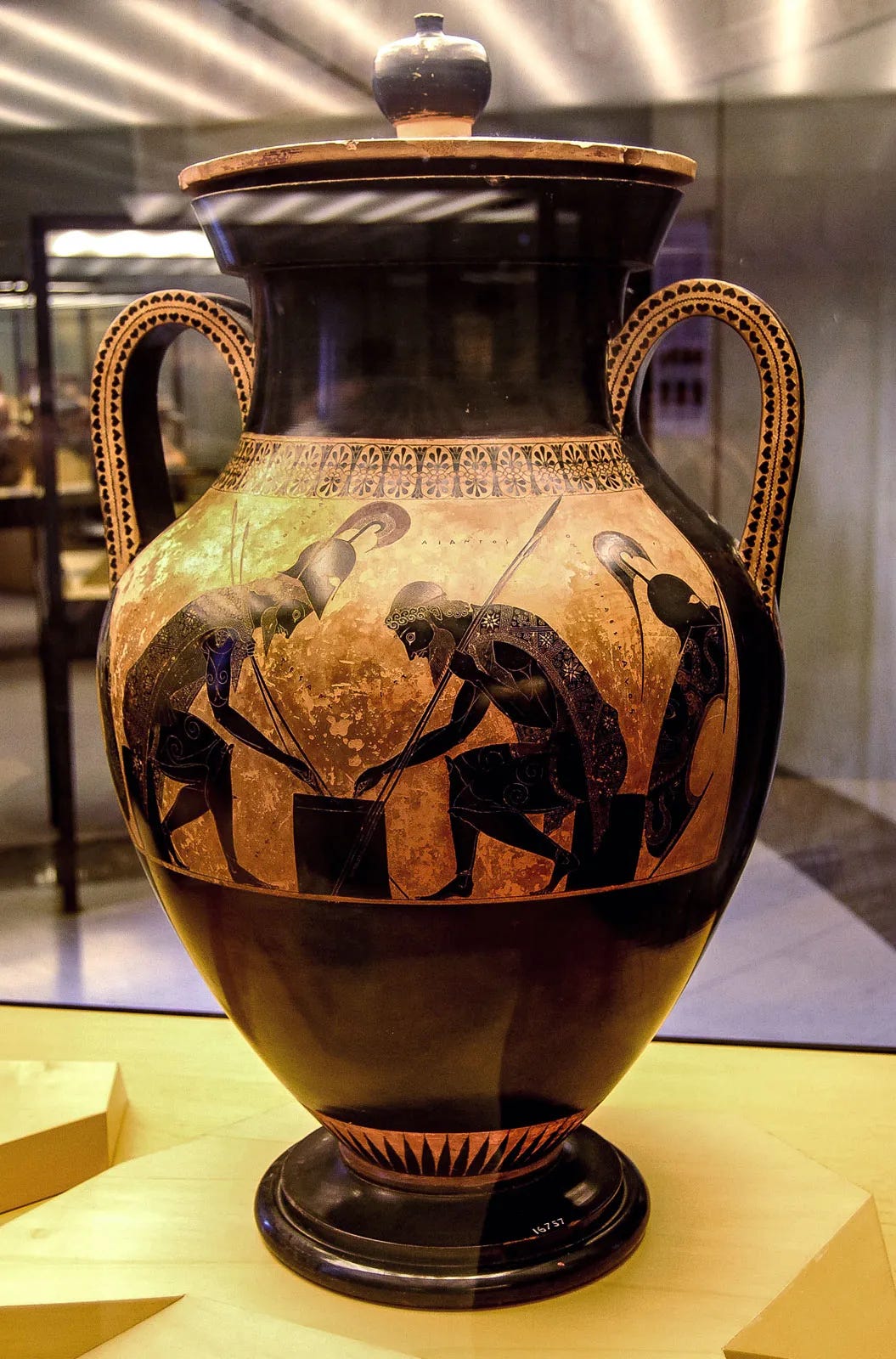

The cover of On Grand Strategy features an illustration of two ancient Greek warriors—Achilles and Ajax—based on the iconic image depicted on ancient Greek pottery (most famously on an Attic black-figure amphora by Exekias from around 540–530 BC).

In the original artwork, Achilles and Ajax—both great warriors of the Trojan War—are shown hunched over a game board, engrossed in a moment of strategic thinking.

Here are 11 lessons I learned from On Grand Strategy:

1. Grand strategy is the art of achieving lofty aspirations with limited means.

People have long faced the enormous gap between what they hope for and what they can hope to get. This dates back, Gaddis suggests, “probably to the first prehuman who figured out how to get something it wanted, using whatever means happened to be available.”

Elsewhere, Gaddis has stated that grand strategy is “about how one uses whatever one has to get wherever it is one wants to go.” Which means that “grand strategy need not apply only to war and statecraft: it’s potentially applicable to any endeavor in which means must be deployed in the pursuit of important ends.”

Grand strategists can sometimes accomplish feats that are seemingly beyond their capabilities. This requires knowing how to allocate one’s limited resources for maximum effect without overstretching yourself.

The greatest strategists in history are remembered not just for what they accomplished, but for how improbable their success seemed at the start. Lincoln took office as the leader of a fractured country, fought and won the bloodiest war in American history, and ended slavery—all without an elite education or military background. His rise defied expectations. Augustus pulled off an even trickier balancing act, turning Rome from a republic into an empire without ever declaring himself emperor, even though his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, had been murdered for seeking too much power. Both men changed history by doing far more than anyone thought they could.

Your life experiences are fleeting, information you read tends to fade, your vision for your future is lofty but unclear. Grand strategy involves drawing useful and actionable information from the trials of our lives and the information we consume to construct a firm bridge between our existing reality and our imagined future.

2. Foxes are better than hedgehogs at forecasting the future.

On Grand Strategy offers a framework provided by the political philosopher Isaiah Berlin, in his 1953 essay The Hedgehog and the Fox.

The title comes from a quote attributed to the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: “A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Isaiah Berlin placed thinkers into two general categories:

Hedgehogs inflexibly view the world through a single overarching idea (e.g., Plato, Hegel, Marx)

Foxes, who draw from multiple frameworks and experiences that are often contradictory (e.g., Aristotle, Shakespeare, Lincoln)

Decades after Berlin offered this framework, the political psychologist Philip E. Tetlock sought to determine the factors that contribute to accuracy in forecasting future events.

Tetlock and his team collected data from experts in universities, governments, think tanks, foundations, international institutions, and the media. Tetlock found that “Who the experts were—professional background, status, and so on—made scarcely an iota of difference. Nor did what the experts thought—whether they were liberals or conservatives, realists or institutionalists, optimists or pessimists.” But how the experts thought—their style of reasoning—did matter.

The critical variable turned out to be self-identification as “foxes” or “hedgehogs” when shown Berlin’s definitions of those terms. The results were unequivocal: foxes were far more proficient predictors than hedgehogs.

Surprised by the results, Tetlock set out to figure out what made his “foxes” better forecasters than his “hedgehogs.”

The key difference is that foxes pull information from a wide range of sources, piecing things together intuitively rather than relying on rigid, all-encompassing theories. They don’t believe politics can be reduced to a simple, mechanical science and approach their own ideas with humility. They are open to criticism and revision. Foxes are often too nuanced for the spotlight. They hedge their bets, qualify their claims, and don’t make for compelling TV guests or easy policy advisors. I’m reminded here of when careful scientists couch their findings in phrases like “This may suggest that…” and then retards online reply “Ho ho, ‘may suggest?’ I guess this so-called ‘expert’ doesn’t really know anything.”

Hedgehogs, on the other hand, have no such reservations. They dismiss self-doubt, double down when challenged, and assert big, sweeping explanations with absolute confidence. If they start digging themselves into a hole, they don’t stop—they just dig deeper. Their certainty makes them sound persuasive, even when they are completely wrong. But their predictions usually fall flat because they’re too committed to their own narratives to adapt. Anonymous social media accounts with large followings are usually hedgehogs.

From all this, Tetlock distilled a basic theory of good judgment: the best thinkers are self-critical. They recognize how unpredictable the world is, remember and learn from their mistakes, adjust their beliefs when new evidence comes in, and ultimately make better predictions over time. “In short,” Gaddis writes, “foxes do it better.”

3. Plans are useless. Planning is essential.

Gaddis has asked, “What’s the difference between wisdom and intuition? Wisdom has accumulated over a period of time. Intuition is the heat of the moment. The more wisdom you have, which is another way of saying ‘more training,’ which is another way of saying ‘more experience,’ the more wisely you’ll make decisions in the heat of the moment.”

There’s a key difference between knowing your destination and knowing the path you will take to get there. A typical commercial airplane is off course 90% of the time, yet it almost always arrives at its destination because it knows exactly where it’s going and makes constant small corrections along the way. You cannot know the exact path to your goal in advance. The real purpose of planning is so that you remain aware that a possible path exists. You’ve heard the statistic that 80% of new businesses fail in their first five years, but a far more interesting statistic is that nearly all of the businesses that succeeded did not do so in the original way they had intended.

If you look at successful businesses that started with business plans, you will commonly find that their original plans failed and that they only succeeded by trying something else. It is said that no business plan survives contact with the marketplace. You can generalize this and say that no plan survives contact with the real world.

You shouldn’t blindly stick to a plan without keeping your bigger goals in mind. Let’s say everything is going smoothly, but then an unexpected opportunity pops up. Do you ignore it to stay on track, or do you pivot and take the opportunity, even if it throws off your original course? This is when you need to pause and reassess—does the opportunity move you closer to your real goal, or is it just a distraction? A plan is only as good as the information you had when you made it. If something new comes along that changes the equation, you have to be honest with yourself about whether sticking to the plan still makes sense. Sometimes, a detour can get you where you want to go even faster. Other times, chasing every opportunity just pulls you further off course. The key is knowing the difference. If you stick too closely to your original plan, if you attempt to forge causal chains, then unexpected events will throw you off course. Seize unexpected opportunities while retaining objectives. In the military, missions are given with objectives and intent, that way if the leader on the ground recognizes another objective would better match the intent of the mission, they can change course.

Remember that old Mike Tyson quote about how “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face”? That doesn’t mean Tyson didn’t have a plan when he entered the ring. That doesn’t mean he didn’t train or strategize.

Here’s another quote attributed to the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: “We don't rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.”

Even if, in moments of conflict, or what Clausewitz described as “friction” in the context of war, unexpected events occur for which your training did not prepare you. You still need plans. You still need to train.

Wise decision-making isn’t about simply finding the right answer; it’s about maintaining focus on a big goal while also staying aware of the changing circumstances around you. It’s about killing a bad strategy before it kills you.

4. The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.

Great leaders are often undone by conflating means with ends, thinking that by virtue of their desiring a particular outcome it will naturally come to pass. In the process, they neglect the practical strategies which brought them fame and glory in the first place.

To resolve this, Gaddis merges Berlin’s essay with Fitzgerald’s remark that “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function” is the mark of a first-rate intelligence. I’ve always liked the full quote: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless yet be determined to make them otherwise.”

Leo Tolstoy embodied this kind of thinking. His writing—especially War and Peace—has lasted because he balanced a hedgehog’s sweeping view of history with a fox’s eye for detail. For anyone thinking strategically, this is the key: keeping the big goal in sight while managing the everyday obstacles that stand in the way.

5. Common sense is like oxygen: the higher you go, the thinner it gets.

The book cites a problem Henry Kissinger identified long ago: “the ‘intellectual capital’ leaders accumulate prior to reaching the top is all they’ll be able to draw on while at the top.”

The problem is that as you climb up, and achieve success after success, you might come to neglect the very principles that fueled your rise in the first place.

This is why training is so important. The ability to draw upon principles extending across time and space, so that you’ll have a sense of what’s worked before and what hasn’t. Such training, Gaddis suggests, is “the best protection we have against strategies getting stupider as they become grander, a recurring problem in peace as well as war.”

Relatedly, Robert Greene has said, “People don't understand that the person above them who seems so powerful and in control often has insecurities. The truth is, the higher up you go in a hierarchy, the more insecure you become. The more you worry about whether people truly respect you.”

The fear of making a mistake (and preferring to fail passively) can lead people to overlook common sense approaches. Turning down an invitation to appear on the biggest podcast in the world while campaigning for president, for example.

6. Leaders must appear to know what they’re doing, even when they don’t.

Decisions, particularly in positions of responsibility, usually have to be made before all of the facts can be gathered.

“For a man to achieve all that is demanded of him, he must regard himself as greater than he is.” — Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Remember the definition of Grand Strategy: The application of limited means to accomplish aspirational ends.

“Means” here can refer to material resources. But means can also encompass mindset, or how you view yourself. Again, how far this goes is limited. You can only stretch your self-image so much before it becomes too distant from reality or evokes serious doubt and scorn from those around you.

But it is interesting that you can take this immaterial resource (self-image) and magically add an extra 10-20% and get it to work for you. Imagine if money worked this way. Suppose that merely believing you have an extra 20% in your wallet somehow grows the amount of cash you hold.

It doesn’t work for money. But it works for self-appraisal. Believing you are 20% more attractive, or charming, or competent can, at least sometimes, get you a better romantic partner, or job, or reputation than you otherwise would have.

We use our limited means (how you view yourself) to achieve greater ends (whatever our goals happen to be) than we otherwise would have by fudging our self-appraisal just a little bit.

7. Don’t stake your reputation on molehills.

Diplomatic tension arises when political leaders have conflicting interests.

In 432 BC, Athens imposed the Megarian Decree as a strategic measure to weaken Sparta. Megara was closely aligned with Sparta, which was Athens’ main competitor. By restricting trade with Megara, Athens aimed to undermine Megara’s economy and send a clear signal to other states about the consequences of opposing Athenian interests. The purpose was to bolster Athens’ security and maintain its regional dominance.

Later, when Sparta offered to help ease these economic penalties in an effort to lower the rising tensions between the states, the Athenian leader Pericles rejected the proposal. He believed that even a small compromise would undermine Athens' firm stance, so he chose to maintain the strict measures instead. Ruling out diplomacy, this left war as the only alternative.

Pericles convinced himself that he couldn’t concede a molehill—the Megarian decree—without a loss of credibility.

Later in the book, Gaddis draws a parallel to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In both cases, the leaders found themselves entangled in situations where small, seemingly negotiable issues became symbolic of larger ideological battles. Just as Pericles refused to back down on the Megarian Decree, fearing it would undermine Athens’ authority, U.S. leaders in the Vietnam War became increasingly committed to a conflict that was, in part, about maintaining credibility with international allies. Both situations revealed how diplomatic tensions could escalate when leaders feared their credibility was always in doubt.

Still, I could also imagine that from a game theory perspective, incurring massive costs can have unexpected reputational benefits. U.S. involvement in Vietnam probably did send a signal to the Soviet Union that the U.S. was unwavering in its commitment to containing communism. In this light, the costs of the Vietnam War may have been seen by American leaders not just as a matter of credibility, but also as a strategic move in the broader context of the Cold War. By getting involved in such a costly conflict, the U.S. could have been signaling to the Soviet Union and other global powers that it was prepared to make substantial sacrifices in order to uphold its commitments. It also sent a signal to the world that the U.S. was serious about spilling its own blood and treasure on behalf of its allies.

On another, unrelated note, modern readers are often shocked to learn that the Athenians—citizens of a free city who defeated the Persians when they invaded Greece, built the Parthenon, and staged the tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles—also massacred the citizens not of an enemy state but of a neutral power—Melos.

In 431 BC a conflict now called the Peloponnesian War had erupted between two sets of cities, one led by Athens and one by Sparta. It had raged for 15 years when the Athenians demanded the allegiance of the heretofore neutral Melians, whose city traced its origin to Sparta. The Melians balked, and at their request, the leaders of the two sides held a private conference.

The Athenians spoke first. With (to modern readers) breathtaking frankness they dismissed considerations of justice as irrelevant. Justice could obtain only between equals. “For ourselves,” the Athenians said, “we shall not trouble you with specious pretences … since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

As Gaddis writes, “Unwilling to relinquish their independence, placing faith in the hope that the world didn’t really work this way, the Melians refused to yield.”

The Athenians then besieged and captured Melos. They slaughtered all of the adult males and sold the women and children into slavery. We reflect on the horrors of, say, the Vietnam war and feel repulsed. But the only reason we feel repulsed is because we have been immersed in Christian morality for so long. A deviation from the way so many other cultures and times and places felt about what we now consider atrocities.

8. The practice of effective principles precedes their articulation.

On Grand Strategy points out that Octavian, the Roman statesman and leader adhered to Sun Tzu’s teaching from The Art of War:

“[W]hen capable, feign incapacity; when active, inactivity. When near, make it appear that you are far; when far away, that you are near. Offer an enemy a bait to lure him; feign disorder and strike him. . . . When he concentrates, prepare against him; where he is strong, avoid him. . . . Pretend inferiority and encourage his arrogance. . . . Keep him under a strain and wear him down.”

Octavian (who later became known as Augustus Caesar) never met Sun Tzu, yet still channeled his teachings. This is because effective strategies and principles often emerge through practice before they are consciously articulated or codified. Rather than following a written doctrine, Octavian instinctively applied the timeless wisdom of deception, patience, and indirect approaches to warfare and politics. His ability to feign weakness, mislead his enemies, and strike at the right moment mirrored Sun Tzu’s principles, demonstrating that strategic truths are first discovered through experience and only later codified into formal study.

I unknowingly applied this lesson when I wrote this.

9. Equally valid moral ends can collide with no possibility of reconciliation.

There is a chapter discussing Machiavelli. Machiavelli’s critics say that what disturbs them is Machiavelli’s comfort with unscrupulous methods to establish and maintain a powerful and well-governed state.

The book suggests, though, that what really unsettles people is that Machiavelli had inadvertently revealed that there are multiple equally desirable ideals, and that it is impossible to achieve one without sacrificing others. He implicitly recognized that equally sacred ends can collide with no possibility of reconciliation. More on this point here.

10. “Men cannot afford justice in any sense that transcends their own preservation.”

The book borrows the above quote from the political philosopher Harvey Mansfield, generally considered to be Machiavelli’s finest translator.

In 1573, Queen Elizabeth I of England (1533–1603) appointed Sir Francis Walsingham as secretary of state, giving him free rein to protect her and the kingdom by any means necessary.

Given that both the Pope and Philip II of Spain were actively supporting her assassination, Sir Walsingham took extreme measures.

Sir Walsingham built an extensive spy network across Europe, using bribery, blackmail, torture, and espionage to counter threats.

What we like to recall as the Elizabethan "golden age” only survived through surveillance and violence. Queen Elizabeth’s reign relied on intense surveillance and harsh crackdowns on perceived traitors. Unlike her sister Mary, Elizabeth did not execute people for their religion—but she did for treason. She wanted to be loved. But as Machiavelli warned, it is often safer for rulers to be feared.

11. “Details dim the flames fireships require.”

Rationality is an instrument, not an endpoint. The book cites the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, who wrote that “rationality and calculation can be applied only to means or subordinate ends.”

In other words, rationality is not an end in itself. Rather, it is a tool you can use to achieve any number of objectives. We can choose when to deploy our powers of rationality. And we can choose to refrain from applying it to areas where it is perhaps not best suited. Comfort with contradictions allows us to avoid despair.

Rationality can sometimes (not always) be self-defeating. If you are feeling joy, you can easily talk yourself out of it. You can change your mood by reasoning your way into misery. But if you are feeling miserable, good luck trying to talk yourself out of it. It’s not so easy to change your mood by reasoning your way into happiness. It’s not impossible, but it is far more difficult than the reverse.

When rationality becomes entangled in every part of your life, happiness suffers. Does free will exist? Are we just mindless vehicles designed to carry our genes forward? Is love “real” or just a series of chemical interactions in your brain? Does it “make sense” to love your family (or your country) despite your connection being due to an accident of birth? If you start asking whether each and every one of your beliefs, decisions and actions are “rational” or whether they “make sense,” you are setting yourself up to be unhappy. Discussing marital disputes, Jordan Peterson has rhetorically asked, “Do you want to be right, or do you want to be happy?” This question could be applied to other areas of life beyond matrimonial conflicts. Being happy, of course, entails being right some of the time. But being right all of the time is a recipe for sorrow.

Misery is the price of accuracy only if you fail to integrate lightness of being into your outlook. Lightness of being, as Gaddis highlights throughout On Grand Strategy means learning to live with contradictions. Understand your aims, and use your powers of rationality appropriately.

One area where rationality is limited or counterproductive is in the realm of relationships. Emotional attachments can’t be gamified — at least not the kind that anyone wants. No amount of surveillance or strategy will manufacture a healthy relationship, and no TikTok influencer can prescribe the exact formula each person needs to find fulfillment. Relatedly, the economist Thomas Schelling has pointed out that an emotional commitment to one’s spouse is valuable in the coldly rational Darwinian cost-benefit calculus, because it promotes your evolutionary interests of survival and reproduction. Note, though, the ironic twist: A relationship commitment works best when it deflects you from thinking explicitly about your commitment in such calculating terms (the same logic applies to friendship, btw). People who consciously approach their social and romantic relationships in score-keeping terms tend to be less satisfied in those relationships, and are less attractive as social allies and romantic partners.

Rationality is required for happiness. But too much rationality—questioning every single aspect of life and attempting to force it all into a consistent and coherent pattern—will give rise to a bleak mindset.

Recall the famous quote from the statistician George E. P. Box who said “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Or another from the psychologist Nancy McWilliams: “All of us learn soon enough, from the unpredictable nuances that arise from our relationships and social interactions, how hopelessly inadequate our most thoughtful and elegant frameworks are when confronted with the mystery that is human nature.”

Depending on the situation you find yourself in, consider whether you want to be happy, or whether you want to be accurate.

Grand strategy isn’t just about planning—it’s about adapting. It’s about knowing when to act like a fox and when to think like a hedgehog. When to be rational and when to trust instinct. When to stick to principles and when to make compromises. The best strategists, from Augustus to Machiavelli to Queen Elizabeth, understood that strategy isn’t about rigid adherence to a plan—it’s about staying focused on your aims while adjusting to reality.

To this end, Gaddis has stated that “The only bet we’re making is that some of our students, at some point in the future, will be in a position to do some great things. Our only assumption is that, when they reach that point, some of them will remember something of what we tried to teach them. And what was that? Chiefly, I hope, that it’s risky just to make it all up as you go along. That it helps to know something about what’s worked and what hasn’t over a period of time that exceeds your own.”

Of many good posts, this one (so far) gets my vote for top prize. It embodies so many psychological and sociological principles, and is great advice, to boot. I think of myself, first, and then of so many others, that have embarked on decisions without any contemplated strategy. Those of us without some plan fare well by luck some of us fare well, others not so much.

The amazing thing is that we keep forgetting this wisdom from the past and we still need to be told.