Mr. Nobody From Nowhere

What Gatsby misunderstood about social class

In the Satyricon, written by the Roman author Petronius in the late first century AD, one of the characters is named Trimalchio.

Trimalchio is a freed slave who has grown wealthy. He throws lavish parties for guests who come, drink his wine, eat his food, and depart without bothering to ask his name.

In the process of coming up with a title for what would become The Great Gatsby, author F. Scott Fitzgerald considered two other titles: “Trimalchio” and “Trimalchio in West Egg.”

He also considered “Gold-Hatted Gatsby” and “Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires.”

Though Fitzgerald was never satisfied with the final title, it has become one of the best known and most widely read books in American history.

Old money versus new money. The emptiness of ambition. Pursuing a prize that is undeserving of your efforts. People have been discussing these topics for a long time. Even before Fitzgerald wrote this book.

In my more cynical moments, I think one reason The Great Gatsby is assigned in high school is to weaken its effect on us (the same goes for Orwell). Anything we are required to read loses some of its power.

Or, as Shilo Brooks points out from his experience as a professor, “a young person might read a certain book before they’re ready for it and then bounce off it. But if they had read that book at 40, they would’ve loved it, and so that impression stays with them.”

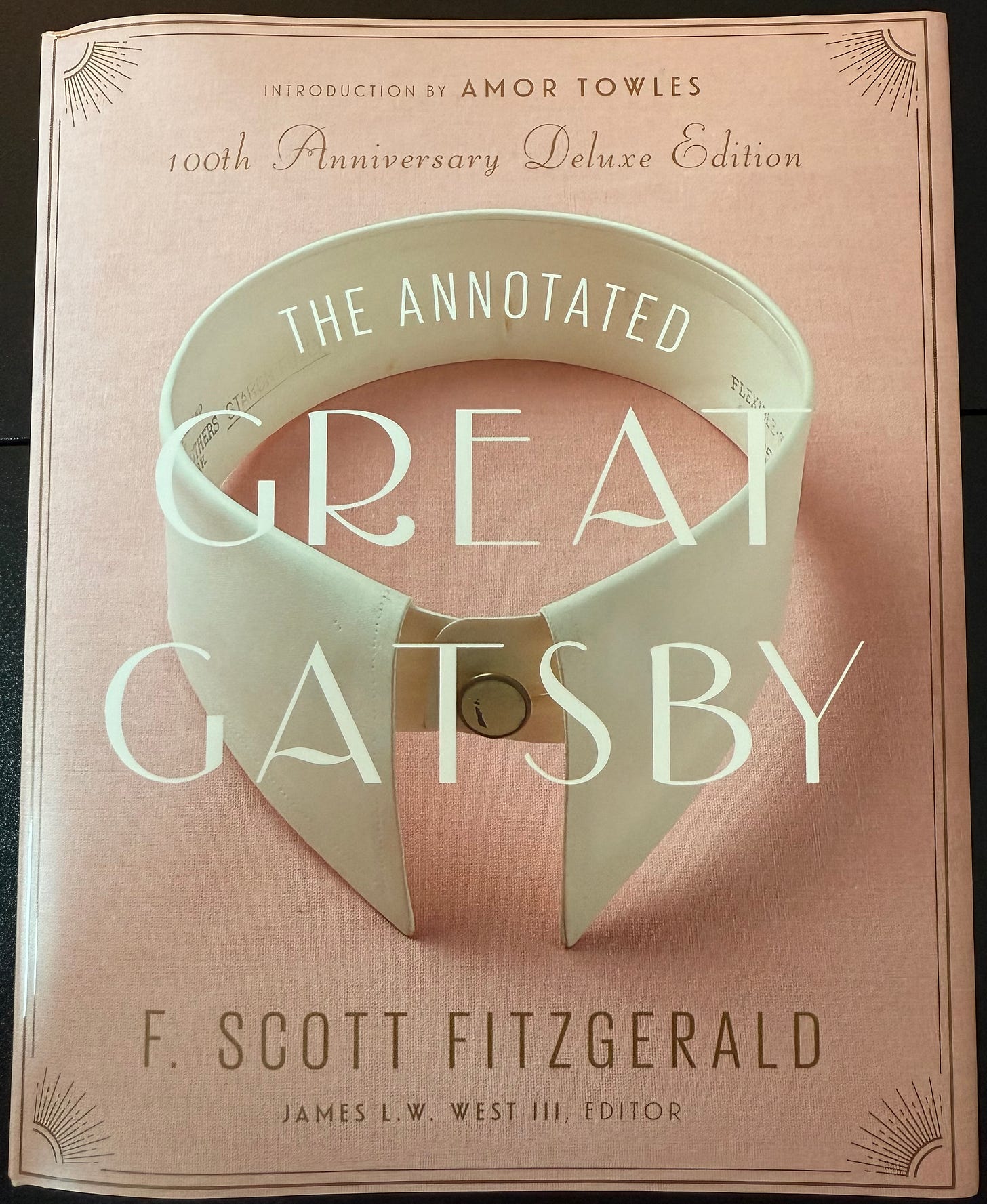

If you’re American, you probably read this book in high school like I did. Then I read it again when I was 23. After learning that a 100th anniversary annotated edition was published last year, I read it for a third time.

Recall that young Jimmy Gatz, while serving in the military, falls in love with Daisy, a woman from a wealthy family.

At the time, he lacked the money and the confidence to propose to her. He is reassigned to fight in Europe during the Great War, and becomes determined to make a fortune so that he can return, marry Daisy, and support her in a way that fits her social class and expectations.

To do this, he remakes himself. Jimmy Gatz becomes Jay Gatsby.

He enters the criminal underworld in New York and earns his money quickly and illegally through bootlegging and gambling. Speed has its costs, though. Gatsby acquires his riches without acquiring the habits that come with it for those born into wealth. He acquires economic capital but not cultural capital. He tries to fake it by implying that he studied at Oxford when in fact he later says he’d undertaken a brief program there while stationed abroad.

Paul Fussell, the social critic and author of Class: A Guide Through the American Status System, wrote that manners, tastes, opinions and conversational style are just as important for upper-class membership as money or credentials, and that to fulfill these requirements, you have to be immersed in affluence from birth. Likewise, the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu stated that a “triadic structure” of schooling, language and taste was necessary to be accepted among the upper class. Bourdieu described the mastery of this triad as “ease”. When you grow up in a social class, you come to embody it. You represent its tastes and values so deeply that you exhibit ease within it.

Gatsby buys a mansion near Daisy and begins throwing extravagant parties hoping Daisy will hear of his gatherings. He imagines that one night Daisy will wander in, see what he has built, and fall in love with him again. Instead, Nick Carraway, Daisy’s cousin, moves in next door. Through Nick, Gatsby meets Daisy again and discovers she is married to Tom Buchanan, a rich, gruff, and unfaithful man who has a mistress named Myrtle Wilson.

Daisy is impressed by Gatsby’s wealth, but she is also indecisive. When Tom confronts Gatsby during a drunken argument at the Plaza Hotel, a catastrophe ensues.

Driving back to Long Island, Daisy, at the wheel of Gatsby’s car, kills Myrtle Wilson, Tom’s mistress. Gatsby volunteers to take the blame to protect Daisy. Myrtle’s husband, George, hunts Gatsby down, killing him before taking his own life.

In the aftermath, Gatsby’s funeral goes nearly unattended. Daisy and Tom disappear abroad. Nick leaves New York. Of course, The Great Gatsby contains far more than this chain of events. The film critic Roger Ebert is credited with saying “It’s not what a movie is about, it’s how it is about it.” The same, of course, applies to novels.

Fanny Butcher, reviewing for the Chicago Tribune, wrote that “It is the story of an almost undreamed of love, of a sordid affair which is a background and a contrast to that love, of a group of that class of America’s ‘nobility’ who take all of the privileges of the European ruling class and assume none of its responsibilities.”

When people in their twenties move across the country, the change often involves some degree of reinvention. They leave behind one version of themselves and begin another.

In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald communicates the struggle of the main characters to find peace in their lives through the shared trait of restlessness. All of the main characters are transplants to New York. Gatsby was raised in North Dakota, served in Europe, and then ended up in West Egg, a fictionalized version of Great Neck on Long Island. In one of their earliest interactions, Gatsby tells Nick, “I thought you ought to know something about me. I didn’t want you to think I was just some nobody. You see, I usually find myself among strangers because I drift here and there trying to forget the sad thing that happened to me.”

Nick Carraway fits this pattern. Although he is Daisy’s cousin and an old acquaintance of Tom Buchanan, he describes them as “two old friends whom I scarcely knew at all.” The details we’re given about Nick’s own life are sparse. He comes from the Midwest, attends Yale, serves in World War I, experiences a failed romance, and then moves to New York for a vaguely defined job on Wall Street. What little we know of his background closely resembles what we initially learn about Gatsby’s.

Interestingly, in the 2013 film adaptation, Nick Carraway (portrayed by Tobey Maguire) twice tells the viewer that he graduated from Yale. In the book, though, Carraway tells the reader “I graduated from New Haven in 1915.” A buried signal intended to communicate to the knowing reader that he went to Yale.

In the book, Nick Carraway’s “New Haven” line contrasts with Gatsby’s (played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the 2013 film) hurried statement to Nick that he was “educated at Oxford.” Nick feels no need to impress anyone (including the reader), while Gatsby feels self-conscious about his social position.

As the novel unfolds, Nick first begins as a detached observer of Gatsby, becomes an acquaintance, and eventually serves as his confidant. Through this growing friendship, Nick learns more about Gatsby’s past. Yet Gatsby never becomes fully clear to him.

Gatsby is a man who has adapted and changed dramatically from his poor beginnings as James Gatz to the glamorous, wealthy, and seemingly urbane Jay Gatsby. I say “seemingly” here because there are moments throughout the novel where he betrays his poverty-stricken upbringing.

For example, there is a quietly devastating social encounter that escaped my attention the first two times I read this book, which occurs in Chapter 6.

Gatsby is standing on his porch when Tom Buchanan, a man named Sloane, and a woman “in a brown riding habit” all approach on horseback. They are out on a casual afternoon ride and plan to stop by Gatsby’s mansion as a convenient pit stop for refreshments.

Gatsby tells them “I’m delighted to see you.” Fitzgerald immediately undercuts this with a narrator’s aside, “As though they cared!” The line is brutal: it tells you, the reader, that Gatsby has badly misread the situation. The social gap between him and these people is larger than he understands. Tom and his two companions would have been just as satisfied (perhaps even more so) had Gatsby not been home at all. Much like how party crashers treat Gatsby’s famous bashes.

What follows is another humiliation. The woman with Tom and Sloane, out of politeness, invites Gatsby to come along to a dinner gathering they are heading to on horseback. Gatsby accepts eagerly, saying he hasn’t got a horse but leaves to prepare his car.

As Gatsby exits, Tom is mystified. “My God, I believe the man’s coming. Doesn’t he know she doesn’t want him?”

The moment exposes several things at once.

First, it shows Gatsby’s social naiveté. Despite his wealth and elaborate performance of refinement, he does not grasp the unspoken rules of old-money interaction. Within Tom’s circle, invitations can be symbolic, casual, or unserious. Everyone is expected to know when not to take them literally. Gatsby, who has learned manners only from observation and deliberate practice rather than immersion from birth, doesn’t grasp this.

Second, by pointing out that Gatsby isn’t really wanted, Tom reinforces the boundary between old money and the nouveau riche.

Third, the scene dramatizes the central tragedy of Gatsby: his belief that access can be purchased. Gatsby has the external symbols (money, clothes, mansion, charm, etc.) but not the habitus. The people he wants recognition from treat him as an amusing curiosity about whom they gossip among themselves, and they treat his mansion as an upscale flophouse.

This brief interaction captures the novel’s larger meaning. Gatsby can get close to the American upper class, but never fully inside. The barrier is not money, but an invisible inheritance of ease and indifference. These are qualities Gatsby lacks because he was not born into wealth.

Still, Gatsby occasionally mogs Tom. During one of his parties he goes around introducing Tom as “the polo player.”

“Oh no,” objected Tom quickly, “not me.”

But evidently the sound of it pleased Gatsby for Tom remained “the polo player” for the rest of the evening.

But later, in Chapter 7, you see Tom flexing on Gatsby. Tom tells Gatsby, “I’ve heard of making a garage out of a stable, but I’m the first man who ever made a stable out of a garage.” A deliberately absurd and boastful remark.

In the early 20th century, it was fairly common for wealthy people to convert old stables (meant for housing horses) into modern garages for automobiles.

This represented “progress” or modernization. Tom claims he’s done the opposite for the purposes of aristocratic leisure.

Throughout the novel Gatsby obviously takes a great deal of pride in his yellow automobile.

Meanwhile, Tom’s horse riding skills keep coming up in conversation. Old money and new.

And, of course, it is Tom in the fateful Plaza Hotel scene who addresses Gatsby as “Mr. Nobody from nowhere.”

In season 2 of the HBO series The Wire, a narcotics trafficker named D’Angelo Barksdale gives his perspective on Fitzgerald’s message in The Great Gatsby:

“He’s saying that the past is always with us. Where we come from, what we go through, how we go through it — all that shit matters. It’s like, you can change up. You can say you somebody new. You can give yourself a whole new story. But what came first is who you really are, and what happened before is what really happened. It doesn’t matter that some fool say he different, because the only thing that make you different is what you really do, or what you really go through. Gatsby, he was who he was, and he did what he did, and because he wasn’t ready to get real with the story, that shit caught up to him.”

You can try to join a different social class, but you will never be fully comfortable within it.

Another of my favorite scenes from The Wire is when D’Angelo takes his girlfriend to a nice restaurant in Baltimore. You can watch it here:

Right away, D’Angelo is uncomfortable when the maitre d’ asks if they have reservations.

He’s not at ease.

After dinner, he asks his girlfriend if the other patrons know that he’s different from them. She replies that there are other black people in the restaurant. But D’Angelo wasn’t talking about race, he was talking about class.

He tries to explain. “Come on, you know, it’s like we get all dressed up, right? Fancy place like this. After we finished, we going to go down to the harbor, walk around a little bit, you know? Acting like we belong here.”

D’Angelo feels like he and Donnette stand out, that others can sense this. Even though the other patrons are absorbed in their own worlds.

Donette replies, “So? Your money good, right?” And she is right. When D’Angelo talks about “belonging,” he seems to sense that there is a club.

For Donette, the only requirement for entry into the club is money. She echoes Gatsby’s vision of the American Dream when she says “Boy, don’t nobody give a damn about you or your story. You got money, you get to be whatever you say you are. That’s the way it is.”

But D’Angelo can’t shake the feeling that this isn’t true.

Interestingly, Gatsby’s absence of polished tact and refinement may have inadvertently precluded Nick Carraway from joining the criminal underworld.

In Chapter 5, Gatsby awkwardly offers Nick a chance to make some extra money: “I carry on a little business on the side, a sort of sideline you understand.”

Gatsby phrases it as a way to help Nick out financially, because Nick is struggling in his bond-selling job. But Gatsby’s offer to Nick is clearly tied to illegal activities, widely understood to be bootlegging and gambling.

Nick narrates:

“I realize now that under different circumstances that conversation might have been one of the crises of my life. But, because the offer was obviously and tactlessly for a service to be rendered, I had no choice except to cut him off there.”

What Nick means here is that Gatsby’s proposal represented a genuine moral temptation. If the offer had come in a different context (e.g., as genuine friendship advice, without any strings attached to the Daisy tea arrangement), Nick suggests he might have seriously considered joining in.

However, Nick immediately shuts it down because Gatsby makes the offer so blatantly transactional. Gatsby is essentially trying to repay Nick for setting up a meeting with Daisy, treating their friendship like a quid pro quo deal. This indelicate framing repels Nick. It feels like a bribe rather than a sincere opportunity. So Nick rejects it outright.

Nick can never fully pin down Gatsby’s identity. Is “Gatsby” an aspirational but inauthentic invention of the young Gatz? Is “Gatsby” a persona he adopted merely to win over Daisy and relive the romance of his youth? Or is “Gatsby” the true version of the self the young James Gatz was destined to become all along despite his humble origins?

Near the end of the book the picture becomes clearer.

When Jimmy Gatz was seventeen and frustrated with his lowly station in life, he saw a millionaire’s yacht moored on a dangerous stretch of Lake Superior.

He borrowed a rowboat and paddled out to warn the owner. The gesture appears courteous, but it is hard not to see ambition working beneath this decision. The owner of the yacht was impressed enough to invite Gatz aboard indefinitely. As Nick later observes, it was this single encounter that set in motion the events that would transform Jimmy Gatz into Jay Gatsby.

At the end of the novel, Gatsby’s father shows Nick something he has discovered among his son’s childhood belongings. It is a daily schedule of “General Resolves” written on the back page of a Western novel. The choice of book is telling. It suggests the ideas that shaped Gatz’s imagination: the romance of the frontier, the promise of American individualism, and the belief that disciplined effort leads to upward social mobility.

The list echoes Benjamin Franklin’s program of self-improvement in his Autobiography. Jimmy Gatz resolves to wake early, practice proper elocution and posture, exercise regularly, and read self-help books, among other to-dos. For decades, readers have argued over what this list reveals about Gatsby.

The list can be read in contradictory ways. On one hand, it shows a sincere and persistent commitment to a dream, placing Gatsby firmly in the admired (and often ridiculed) American tradition (or myth) of the self-made man. On the other hand, it can be read as evidence of inauthenticity, a set of instructions designed to manufacture an artificial self.

Personally, I am inclined to believe that what the list says about Gatsby is less important than where it led him. Gatsby mastered the techniques of self-creation, but he never achieved what he truly desired. He wanted to be accepted without reservation, not merely admired or gossiped about, but counted as one of them.

We are drawn to real-life Gatsbys, especially after their collapse. A young and wealthy visionary who turns out to be a fraud is compelling. When that same figure ascends rapidly and then crashes, the fascination deepens.

The most interesting thing Gatsby says comes in Chapter 8.

Gatsby is finally forced to admit that Daisy really did love Tom.

He says to Nick, “In any case it was just personal.” Just personal.

In that moment, as Lionel Trilling has noted, Gatsby implicitly divides the world into two realms. One is the ordinary human realm. The other is the realm of ideal forms, where Daisy exists not as a real person but as a symbol. Gatsby claims a metaphysical exemption for his ideal relationship with Daisy, which exists on a higher plane than her actual relationship with Tom.

Gatsby treats his own myth as more real than the facts that threaten it. On this point, the late literary critic Harold Bloom observes, “That refusal to surrender to reality kills him, yet it also gives him his peculiar greatness.”

This is one of your stronger essays of late -- the sort of stuff I subscribed to you for.

I'm from a new-money and very complicated family (7/8 biological great-grandparents were working class or grew up in poverty, mother was the result of a teen pregnancy by my working-class Irish grandmother and my grandfather, who was born into poverty in Calabria and raised in poverty in a small town in Canada, and most certainly treated as "other", not white -- and my father's mother, the half-WASP, turned out to not be fully white either via her working-class father -- which was phenotypically apparent).

My mom's adoptive parents were a WASP mother from a downwardly mobile family and another poor Southern Italian immigrant, who eloped against her racist and classist parents wishes and were disowned by them. My adoptive grandfather started a business and by the time they adopted my mom they were well-off. My dad worked for my grandfather and turned the business from a small one into a 8-figure one over my childhood (edit: actually I think it's low 9 figures now, but I'm in my thirties -- and no, I don't have a trust fund, never did).

No one in my family really fits in with WASP culture, rich-people culture, whatever you want to call it. My adoptive grandfather didn't finish high school, and wasn't seen as white in a very white affluent neighbourhood. My mom was acutely aware of and insecure of her differences. My dad was a university drop-out.

I don't think you can ever fit in, even after a few generations. Anyway, I'm downwardly mobile, my husband grew up poor with a single mom and while he has a good job, he's nothing like my workaholic father (I'm much more comfortable with working and middle-class folks and other ethnics so this works for me). I had the grades for an Ivy league, but honestly thought it seemed terrible and I had the privilege to opt out.

The world depicted The Great Gatsby always seemed like pure hell to me. Fitzgerald was a genius.

I went to an affluent high school. I was one of the only kids not wearing designer clothes or driving a new car (still had a car!). I was teased for being "poor" (and after Jersey Shore came out, Italian lol) even though I clearly wasn't.

It's all a load of crap. Seriously, if you came from nothing and have the smarts to be successful, go get yours, but why would you want to be like old money?

Anyway, my caution to you is, because I've seen this in new money -- if you marry and become a parent, do not resent or show contempt to your own child(ren) for growing up with privileges and connections you didn't have. Your kids will not have the same opportunity to be "self-made" in the same way you did, even if they choose an entirely different field and prove themselves in it. But they also won't ever be "old money" in the same way as many Ivy league attendees.

And that's okay.

This is a very timely and well written essay, you do a masterful job of teasing out the complications of Gatsby's story, it is one that is too often repeated.

For almost 5 decades I worked on Wall Street. I am the son of a career military officer and came from a solid and respectable middle class background. I went to a state university of middle rank and did not do graduate school due to my own military service.

When I started in the investment world it was through a firm catering to middle class investors and the industry was divided into the white shoe firms, the wire houses and the bucket shops. Later due to a particular set of knowledge I had developed, I moved from the wire house to one of the white shoe firms, I thought it meant a permanent change in status.

While I made more money and believed my work ethic would allow me to reach the upper strata of the firm it did not. I would find later that the path to the top at that firm was closed to me due to my lack of credentials from the right schools but even more by the lack of blood credentials.

I then decamped to a firm that was dominated by a different ethic- religion- and was again blocked from progress due to factors outside my own efforts.

It took me years to recognize that I was never going to be allowed to succeed as I defined it, and if I did it would be conditional, I would be tolerated for what I could do but never accepted as what I was. It caused years of stress frustration and anger.

Now in my dotage I understand that in the United States we have moved from our ideal of each person being judged by their efforts to a class based society every bit as rigid and exclusionary as the UK or other countries with an aristocratic structure.

High School students are too young to realize the message of Gatsby it is only when one is frustrated in love or business that the lessons can find a way to be understood.