What I’ve Learned After Three Years on Substack

State of the newsletter

From an interview with Jerry Seinfeld:

David Remnick: I was once talking to the writer Adrian LeBlanc, who’s been working on a book about comedy, and I asked, “Who are the two smartest comedians about comedy?” I expected her to name two obscurities. And she said you and Chris Rock, because you study it. You’ve been thinking about this; it’s not just a bunch of jokes.

Jerry Seinfeld: Yes. Chris is the smartest person, maybe, I’ve ever met…I was with Chris a couple of weeks ago, and he was talking about a young comic. He was asking the comedian about what he did that day. And the guy said, “Nothing. But I’m going to do a set tonight.” And Chris explained to him, “You make money during the day. You collect it at night. During the day is where the money is made.”

You make money during the day. You collect it at night. During the day is where the money is made.

Seinfeld is saying that becoming a good standup comic requires you to live life, pay attention to your surroundings, have lots of experiences, and speak with interesting people. Then you take all of this material and convert it into art. Elsewhere in the interview, Seinfeld goes on to say “This is a writer’s game. If you can write, you succeed. If you can’t, you will not make it. The performing, being funny onstage, that’s great. Any comedian can be funny onstage. But the bullets are the writing.”

Good material comes from taking what you have accrued and making it informative, entertaining, or thought-provoking.

As my friend David Perell points out, even full-time writers spend the majority of their time away from their computer. You don’t log 40 hours a week typing away at your keyboard. Doing so would leave you with nothing of substance to say. More from David:

“Experiences become shareable creations the way tree sap becomes maple syrup. It takes 50 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup. So whenever I feel like I don’t have enough ideas to create something meaningful, I go collect more experiences and spend time processing them by writing and talking to friends.”

Most good writing happens beyond the page. Gathering experiences, observing the world, letting ideas take shape. By the time you sit down to write, you’ve already lived through the material. Even if the exact words have yet to come.

Depending on the type of writer you are, reading is also critical. Being social and engaging with others is important. So is solitude and quiet reflection while engaging with ideas.

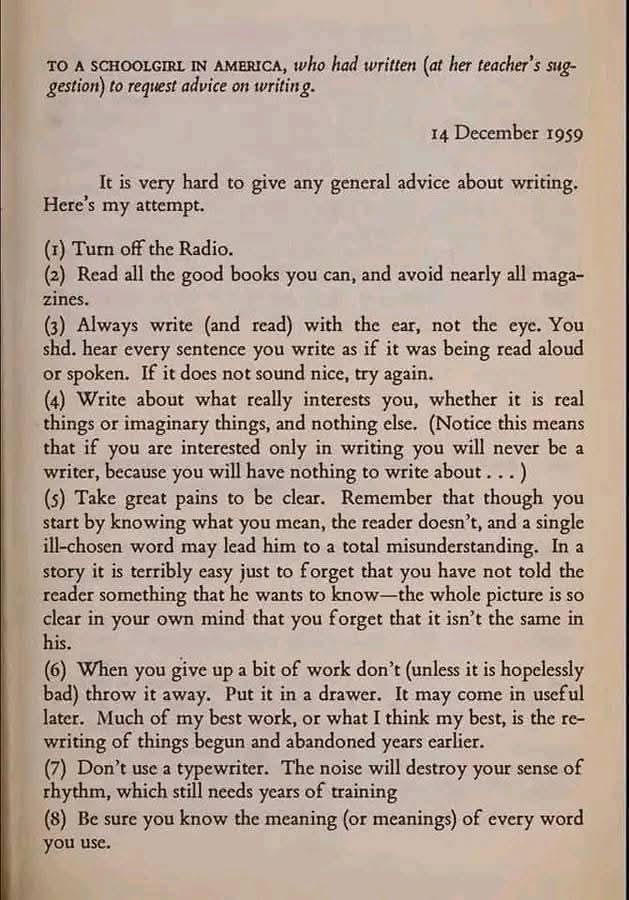

When asked for advice on how to become a better writer, C.S. Lewis shared 8 tips, one of which was “Write about what really interests you, whether it is real things or imaginary things, and nothing else. (Notice this means that if you are interested only in writing you will never be a writer, because you will have nothing to write about…).”

Shane Parrish of Farnam Street writes, “If you want new ideas, read old books.”

Gustave Flaubert once declared, “My life is as flat as the table I write on.” Aside from a few trips abroad and occasional appearances in high-society Paris, he fiercely protected his quiet routine and solitude—conditions he deemed essential to his work. This reclusive tendency is common among public intellectuals; developing the implications of a system of thought often demands long stretches of retreat from public life, as deep knowledge rarely emerges without the private disciplines of reading and writing.

According to some accounts, Carl Jung was known to value solitude deeply and often retreated to his secluded tower in Bollingen, Switzerland, where he read, carved stone, and reflected in silence—often with his pipe in hand. While he did produce a vast body of written work, he did not always enjoy the act of writing in the conventional sense. Jung viewed writing more as a means of clarifying his thoughts and sharing his psychological insights than as a pleasurable pursuit in itself. Jung wrote extensively. But he preferred quiet contemplation with a pipe and a book.

Hemingway compared daily writing to regularly drawing a few buckets of water from a well; each time the water will naturally rise back to its original level. If, however, you suddenly pump out a large amount all at once, you might find yourself without water for a long while. You gotta take breaks on occasion.

Your unconscious spits out material related to whatever you put in. I learned this while writing my book, which consumed my life for the better part of four years. Your unconscious can produce profound insights seemingly from nowhere. But if you spend your days engaged in arguments on social media or whatever, your mind will generate clever dunks during your walks. Read lots of news and current events, and your unconscious will cloud your inner life with gloom and pessimism. Concentrate fully on a project or a piece of art, though, and ideas will come to you. The more mindless external stimuli and meaningless minutiae you absorb, the more mental clutter will block your creativity. If you want those gifts, if you want your unconscious to deliver creative and insightful outputs, you have to protect its inputs.

From mathematician Richard Hamming’s famous 1986 lecture, “You and Your Research”:

“Everybody who has studied creativity is driven finally to saying, ‘creativity comes out of your subconscious.’ Somehow, suddenly, there it is. It just appears. Well, we know very little about the subconscious; but one thing you are pretty well aware of is that your dreams also come out of your subconscious. And you're aware your dreams are, to a fair extent, a reworking of the experiences of the day. If you are deeply immersed and committed to a topic, day after day after day, your subconscious has nothing to do but work on your problem. And so you wake up one morning, or on some afternoon, and there's the answer. For those who don't get committed to their current problem, the subconscious goofs off on other things and doesn't produce the big result. So the way to manage yourself is that when you have a real important problem you don't let anything else get the center of your attention - you keep your thoughts on the problem. Keep your subconscious starved so it has to work on your problem, so you can sleep peacefully and get the answer in the morning, free.”

At this point, being a regular reader of books will put you ahead of many writers who are merely reacting to the latest headlines and trending topics. Even though I read a lot, I can be guilty of this myself. I’ve noticed that when I write about topics directly or indirectly related to politics and culture war stuff, these posts get a lot more readers to convert to paid subscribers. The occasional culture war essay or comments on topical events. These usually yield a lot of paid subs, which allows me to spend more of my time thinking and reading and writing about the things that I find more interesting.

A few people have asked how much time I spend running this newsletter. In terms of actual, physical, writing, re-writing, and editing, maybe 8 hours a week. But I spend the majority of my waking hours—maybe 50-60 hours a week—reading, thinking, note-taking, brainstorming, speaking with other writers, academics, journalists, and so on. All of that goes into my writing. When I'm in the shower mulling over a recent psychology paper or having a coffee chat with a professor or reading my Kindle app on the train or dictating notes on my phone when I'm out for a walk, does that count as “working on my Substack?” I also occasionally write about my life more generally. Unclear whether “living life” also counts as being on the clock. In a given week, we’re awake for 110-120 hours. So in a typical week, I either put in about 8 hours into my Substack or 100+. Depends on how you look at it. A lot of jobs that require creativity or innovation or unique skill sets are like this. In a way, you’re always on the clock.

I launched the first iteration of this newsletter in January of 2020 on MailChimp. A little over two years later, in April of 2022, I moved over to Substack. I shared my thoughts after year one here, and year two here. When I wrote my last newsletter update a year ago, this newsletter had 55 thousand total subscribers and 2,386 paid subscribers.

Today there are more than 71 thousand subscribers and 2,747 paid subscribers.

There’s a number floating around out there suggesting you can expect 10% of your free subscribers to go paid. In my experience (and from what I’ve heard from other Substack writers), though, the number is typically something closer to 4 or 5 percent. Paid subscriber growth has slowed somewhat, perhaps because there are more writers on Substack and it’s becoming harder for readers to pay individual subscriptions for each writer they like.

Still, as I’ve mentioned before, I haven’t concentrated much effort on growth for the sake of growth. More than one popular Substacker has told me that they have become a little too preoccupied with tracking metrics, open rates, growth, etc. This to me makes sense if you are just starting out and are searching for feedback from the world that you are writing something worth reading. But at a certain point, each additional minute you spend on growth hacks or whatever is a minute you’re not spending actually living life, reading books, and doing things that make your writing interesting.

With the rise of AI, having a unique point of view is becoming even more important. I worry about whether LLMs are going to make people generally wary of any text they encounter online. Why would you pay for something you suspect might be written by a robot? If a human didn’t care enough to write it, why should you care enough to read it, let alone pay money to do so?

For this reason, I suspect personal writing is going to become more important. I wrote a whole book of personal writing and didn’t enjoy it nearly as much as I enjoy writing about psychology, social trends, status games, etc. Given the way things are going, though, I’ll probably share more occasional personal essays.

I also regularly do livestreams now, usually on Wednesdays at 8pm ET though this can vary. Anyone (both free and paid subscribers) can watch them live. But only paid subs can watch or listen to the recordings.

Throughout building my newsletter, I haven’t implemented much readership growth advice from other people. Growth is not number one on my agenda. This might be why I haven’t received spectacular bursts of attention and subscribers. I’ve seen other writers who share charts indicating rapid and punctuated instances of major subscription increases. My Substack is not that way. Similar to Twitter, my experience with newsletters (both the first Mailchimp version and now Substack) has been one of gradual, reliable growth, brick by brick, fueled primarily by word of mouth. I think growth is important, it’s nice to see, and I’m not shy about sharing my work online and on Twitter. Still, growth has never been my primary goal.

The psychologist (and excellent Substacker) Steve Stewart-Williams has written that the “3 most beautiful words in the English language: New Paid Subscriber.”

I remember when I started the first iteration of this newsletter on MailChimp, I added a little donorbox button for readers to tip me if they wanted. Each time I saw $5, $15, or (incredibly) the occasional $100+ donation, it encouraged me to keep going.

Three years after joining Substack, we have jumped up to the number 3 science newsletter on this platform.

Writing online started as a side hustle when I was in grad school. The original iteration of my newsletter began as a hobby, and I found myself putting more and more work into it. It has become a primary income stream, which was unplanned. I’ve discovered that few things give me more pleasure than sharing my writing directly with my readers. I’m happy to support other writers I enjoy reading, and I’ve always welcomed subscribers to support me. After the first year of building a newsletter and seeing the extent of its reach, I realized I could potentially earn a living as a writer. Still, I periodically offer free upgrades to readers who are unable to afford a paid subscription. I grew up poor and spent much of my young adulthood broke, so while I enjoy getting paid for my work, I try to make it accessible to everyone.

This underscores the need for independent writing. Weekly essays delivered to your inbox on a reliable day at a reliable time (Sunday morning), along with bonus posts and recommendations, without any ads, affiliate links, pop-ups, SEO bait, or any other increasingly familiar features of our online landscape.

Mechanical consistency is an underrated approach to building a readership. Everyone wants the secret sauce or the smash hit viral article. But the real secret is to develop a reliable and dependable writing schedule.

The psychologist Dean Keith Simonton points out that one notable attribute that distinguishes high performers is volume:

“A small percentage of workers is responsible for the bulk of the work...the top 10% of the most prolific elite can be credited with 50% of all contributions, whereas the bottom 50% of least productive workers can claim only 15%...the most productive contributor is about 100 times more prolific than the least.”

This goes for anyone in a competitive domain that requires some creativity. It definitely applies to podcasters (the vast majority of podcasters never produce more than 20 episodes) and newsletter writers (so often you’ll see people write a few good Substack posts and then go dark). Regular output is key. Do the work, accept that most of your work will be fair-to-middling, and be grateful for the occasional home run.

Writing is like going to the gym. Don't over-romanticize it. You go there, you do the thing. Do it enough times and magic will sometimes appear. Gradually you get better at the craft; or you’ll look better with your shirt off. Just stick with your routine.

Interestingly, 19th century English novelist Anthony Trollope’s literary reputation suffered as a result of the revelation that he treated writing as a routine and humdrum task rather than a romanticized and divine calling. Many people prefer the myth, not the reality:

“[Trollope] made up his mind to do his stint of writing no matter what happened. Often he would write on trains. What writers call 'waiting for an inspiration' he considered nonsense. The result of his system was that he accomplished a vast amount of work. But, by telling the truth about his system, he injured his reputation. When his 'Autobiography' was published after his death, lovers of literature were shocked, instead of being impressed by his courage and industry. They had the old-fashioned notion about writing, which still persists, by the way. They liked to think of writers as 'inspired,' as doing their work by means of a divine agency.”

Many of you are recent subscribers, coming here after having read my debut book Troubled. If all goes well, there will be a film adaptation.

One thing I learned recently is that yes, you can use social media and your newsletter to promote a book. But you can also use your book to promote your newsletter and your other platforms.

When you have a book out and it gets some buzz and attention, you get invited on podcasts. Maybe you get a segment or two on TV. Most people who see you on a 3 minute TV segment or listen to you on a long form podcast aren’t going to buy your book. That’s just the reality. A small number of listeners and viewers, though, will look you up online.

Perhaps they decide to follow you on X or Instagram. Or sign up for your newsletter. Maybe they follow you for a while. If, after a few weeks or a few months, they like what they see, they consider getting your book. Maybe they sign up for a paid newsletter subscription.

The funnel goes something like you listen to the person on a podcast —> follow them on X —> enjoy their tweets —> sign up for their newsletter —> take pleasure in or find useful information in their writing —> get their book and/or subscribe for premium membership.

Many people have noted how difficult it is to sell books. Even celebrities with millions of followers are having difficulty moving as many copies as their sizeable social media platforms would supposedly predict.

According to literary agent Carly Waters, a successful memoir must have two key elements: accessibility—a point of entry that readers can grasp and trust—and second, the more elusive quality of unbelievability—the feeling that the writer’s life is so different from our own that we can’t help but be intrigued. And crucially, this accessible-yet-unbelievable story must also be “very well told.” When I was writing Troubled there was an ongoing, never-ending program running in the back of my mind about how to best tell the story. The specific vignettes, the takeaways, how each scene would unfold, why I was highlighting each event, the emotional rhythm, how each chapter had to be self-contained, etc. It was an unpleasant experience and gave me a newfound respect for people who write stories as a profession.

As with anything, there’s an element of luck that goes into a book’s success. Still, things aren’t entirely up to fortune. Authors have some degree of control.

Platform matters. The medium through which people become accustomed to your work matters. Generally speaking, people will enjoy a creator’s work in the mode they’re used to. For example, if readers enjoy reading a writer’s material online, then they’ll most likely enjoy reading it in book-form, too. But if you’re used to watching a TikTok influencer on your phone or a movie star on the big screen, it’s less clear if that will translate into book sales.

If you want people to read your book, it helps if they’re accustomed to reading your writing. I’ve heard that popular podcasters who become authors often sell far more audiobooks than hardcovers or ebooks. Which makes sense. People are used to hearing their voice. They’re comfortable with that person in their ear. So they buy the person’s book in the format they’re accustomed to. All this implies that if you want people to read your book, start a newsletter. If you want people to listen to your book, maybe podcasting or TikToking is the right call.

Candidly, there were moments when I worried whether my book Troubled would retain relevance by the time it launched. Particularly the final few chapters where I write about the culture of elite colleges. Last year, after the resignations of two Ivy League presidents, my concerns were put to rest. Whatever has infected the culture of higher ed remains as salient as ever. It was already apparent by the time I arrived at Yale in 2015. I’m glad those chapters of Troubled exist as firsthand documentation of the moment when this new wave of political correctness began spilling out of colleges.

There does seem to be something of a vibe shift, even in elite universities. In the past 18 months, three different Ivy League presidents have resigned (at Harvard, Penn, and, most recently, Columbia).

I’ve been surprised at how many colleges have invited me to speak on their campuses. Including Claremont McKenna, Cornell, Yale, Harvard, Princeton, WashU in St. Louis, Westminster College, and others. At one campus, I told a story about how the day after the 2016 election, classes were cancelled at Yale. After the talk, three undergrads came up to me and said “We’ve heard you tell that story before. After the election this past November we hoped they would cancel class for us too, but no luck.” Seems that tempers have cooled.

Another thing I’ve learned about writing is that books can strengthen people’s real-life relationships. Sometimes people say they feel they “know me” after reading my Substack or reading my book. It’s not really true. You know the small part of my life that I share. As Kevin Kelly writes in his compendium Excellent Advice for Living, “You see only 2% of another person and they see only 2% of you.” With writers, you can bump it up to maybe 4 percent. With memoirists, 20 percent or 30 percent. But 70 percent remains inaccessible (sometimes even to ourselves). Still, it’s unsurprising for readers to develop parasocial bonds with authors. More meaningful, though, are the messages I receive from people who listen to my book with their kids, or friends, or loved ones and they tell me it created a space for them to be more open with one another about their own experiences and memories. The other day a father wrote to me explaining he and his kids listened to my audiobook during a road trip and it created a space for them to express their reflections about difficult events in their own family. Writing can bring readers closer to people in their own lives and strengthen their existing relationships. Social relationships are more important than parasocial ones.

Here are some notable posts throughout the past year:

Why Young Women Are Becoming More Liberal Than Young Men: The Gender-Equality Paradox

The True Self is the Person You Want Others to Believe You Are: The psychology of authenticity

You Can’t Treat Me This Way: The evolutionary logic of anger

Thanks for your support. Thanks for reading.

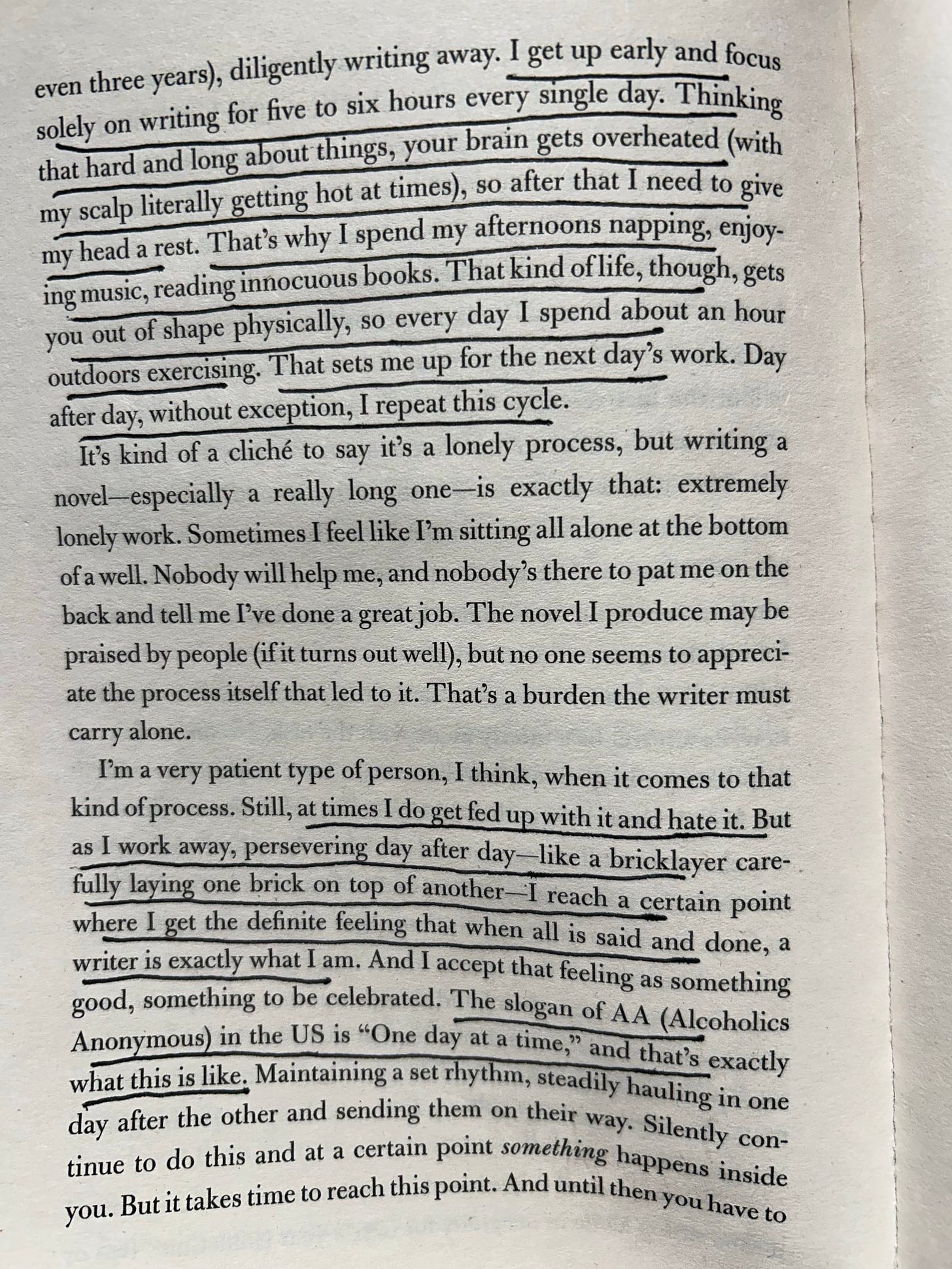

I’ll conclude here with this passage from Haruki Murakami:

“Paid subscriber growth has slowed somewhat, perhaps because there are more writers on Substack and it’s becoming harder for readers to pay individual subscriptions for each writer they like. “

Definitely….💯 also limited time to follow multiple public figs.

Super helpful.